Citizens’ Assemblies: Democratic Responses to Authoritarian Challenges in Central and Eastern Europe

A PDF version of the text below is available to download here.

"If we had tools like this in the 1990s, we might have avoided the Yugoslav wars."—Member of the 2024 Kosovo Citizens' Assembly

Summary

Amid the decline of democracy around the world, citizens’ assemblies are increasingly being employed to tackle complex policy issues, counteract populism, and rebuild trust. Central and Eastern Europe, in particular, faces internal democratic challenges and external threats from Russia and, in some countries, from China. Both these powers exploit societal disillusionment through disinformation and interference. Despite these challenges, the region’s strong tradition of civil society and innovation offers a foundation for democratic resilience.

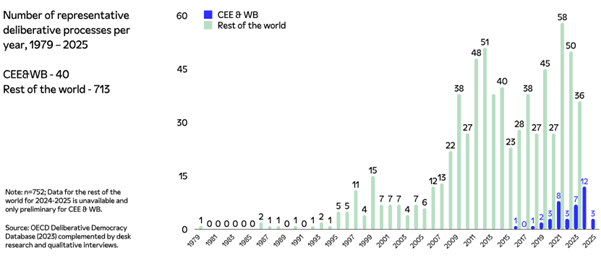

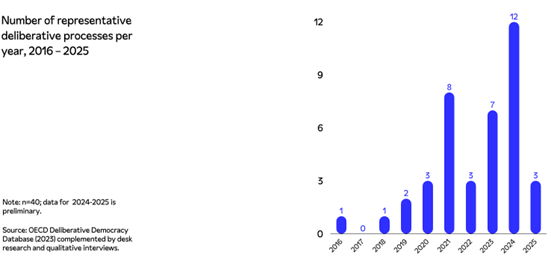

This paper examines how citizens’ assemblies can help address authoritarianism in the region by enhancing democratic resilience and protecting against societal division. Through an analysis of 40 case studies, it reveals a growing “deliberative wave” since 2016, with the number of countries implementing assemblies expected to double by 2025. Qualitative interviews with practitioners highlight both the challenges, such as securing political will and resources, and the resilience and creativity in overcoming them. The paper concludes with recommendations for amplifying the impact of citizens’ assemblies, stressing the importance of upholding deliberative standards and building systemic infrastructure.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from the expertise and feedback of Claudia Chwalisz, Ansel Herz, Hugh Pope, Lucy Reid, and James Macdonald-Nelson (DemocracyNext); Éva Bordos (DemNet); Andrea Chulkova and Žofie Hobzíková (Czech platform for Citizens’ Assemblies); Nicole Curato and Lucy Parry (University of Canberra); Marcin Gerwin (Center for Blue Democracy); Maria Jagaciak (Chancellery of the Polish Parliament); Damir Kapidžić (University of Sarajevo); Jonathan Moskovic (Francophone Brussels Parliament); Ines Omann (Austrian Foundation for Development Research); Dino Pasalic (IWM Vienna); Teele Pehk (DD Foundation); Paulina Pospieszna (Adam Mickiewicz University); Gazela Pudar Draško (University of Belgrade); Tijana Rosandic (Parliament of Montenegro); and David Schecter (Democracy R&D).

This paper was written as part of the Europe’s Futures fellowship, an initiative by the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM Vienna) and ERSTE Foundation.

Note on methodology

The scope of this study is Central and Eastern Europe, including the Baltic states and Western Balkans. There is admittedly a rich diversity of histories and regimes within the region, but also shared contextual characteristics relevant to this study. This includes geopolitical instability and uncertainty caused by close proximity to a neighbor that harbors imperialistic ambitions, a traumatic history inflicted by its colonial practices during much of the 20th century and the legacy this has left, and a period of democratization over recent decades.

The examples of citizens’ assemblies and juries analyzed in this study draw upon data from the OECD Deliberative Democracy Database (2023), complemented by desk research to include examples that are ongoing or planned in 2024–2025. Examples included in this study meet the OECD criteria of three defining features: sufficient time for deliberation (at least 2 days), representativeness achieved through random sampling (sortition), and impact (a formal connection to public decision-making). Examples for ongoing or planned processes were included based on the available data in relation to those criteria.

To capture insights and draw learnings on implementing citizens’ assemblies and juries in the region, qualitative interviews were conducted and feedback sought from deliberative democracy practitioners, scholars, and policymakers from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Montenegro, Poland, and Serbia.

Introduction

In recent years, the global democratic landscape has faced unprecedented challenges, with authoritarianism on the rise and democratic norms increasingly under threat. Central and Eastern Europe finds itself at the forefront of this troubling trend, experiencing a resurgence of illiberalism weakening democratic institutions and eroding civil liberties.

Against this backdrop, there is an urgent need for innovative democratic mechanisms that can effectively counter these authoritarian challenges and offer new ways to give people a more meaningful role in decision making. Citizens’ assemblies, a form of deliberative democracy, have emerged as a promising approach. These assemblies bring together randomly selected citizens to learn about contested issues, deliberate and develop collective recommendations.

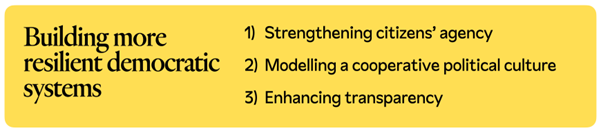

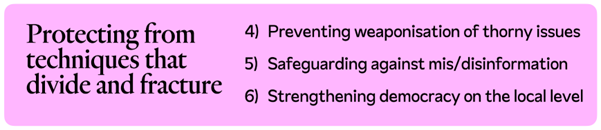

This paper explores the potential of citizens’ assemblies as a democratic response to the authoritarian challenges in Central and Eastern Europe. By examining their role in building more resilient democratic systems and by protecting from techniques that divide and fracture, this study aims to demonstrate how citizens’ assemblies can contribute to the resilience and renewal of democracy in the region.

The paper is structured as follows: the first section provides an overview of the current democratic decline in Central and Eastern Europe. The second section introduces the concept of citizens’ assemblies and discusses their qualities. The third section outlines the ways they can contribute to addressing authoritarianism in the region. The fourth section analyzes case studies of citizens’ assemblies in the region, highlighting the main trends and challenges. Finally, the paper concludes with recommendations for amplifying the impact of citizens’ assemblies in the region.

Global democratic backslide

Today, large parts of society are reconsidering their consent to an electoral democratic system that has been struggling to live up to their expectations. The 2023 V-Dem report reveals that democracy levels worldwide have regressed to those of 1985, with 71% of the global population—5.7 billion people—now living under autocracies (V-Dem 2024). Trust in government is at a low, with only 39% of citizens in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries expressing confidence in their national governments (OECD 2024). In contrast, businesses and non-governmental organisations enjoy higher trust levels (Edelman Trust Barometer 2023). The recent European Parliament elections highlight a worrying trend: the rise of populist leaders who undermine democratic principles to entrench their power (Svolik et al. 2023).

The underlying causes behind the global democratic backslide are many. Central to it is a political system that does not provide people with genuine opportunities for influencing the decisions that affect their lives and leaves citizens feeling disillusioned. According to the OECD, the perception of having a say in government actions is a critical driver of trust (2024). Persisting social and economic inequalities are fuelling a turn towards authoritarian structures (Solt 2012). Climate anxiety, particularly among young people, further exacerbates disenchantment, as inadequate governmental responses to climate change lead to feelings of betrayal and disengagement (Hickman et al. 2021).

Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe is in a vulnerable moment as it faces a wave of populism, polarization, and growing public disengagement against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine. Over the past 15 years, the region has been gripped by a “polycrisis,” present in Europe more broadly, including the eurozone and migration crises, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the climate crisis, all of which have strained democratic institutions (Krastev and Leonard 2024).

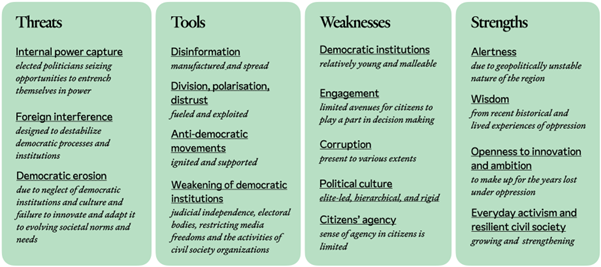

The table below attempts to broadly identify the main threats to democracy and indicates some of the tools used to undermine it in the region. It identifies the relative weaknesses and the strengths of democracies in Central and Eastern Europe that potentially make them vulnerable to but also provide windows of opportunity to resist.

Threats and tools

Internal power capture

Democratic backsliding in numerous Central and Eastern European countries is largely driven by internal power capture. Relying on techniques such as spreading disinformation and fuelling division, populist leaders capitalise on people’s frustration and fear to secure support for agendas that promise quick and simple solutions. Once elected, a gradual weakening of democratic institutions begins in an attempt to consolidate power. This includes undermining judicial independence, restricting media freedoms, and stifling civil society (Levitsky et al. 2010; Guriev et al. 2020; Prospieszna et al. 2024). For instance, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán continues to dismantle democratic institutions, Serbia is experiencing stronger authoritarian tendencies, and Slovakia’s new populist-nationalist coalition has begun cracking down on independent media (Anghel 2024; Bechev 2024; Cameron 2024). Although recent elections in Poland promise renewal, years of eroded human rights and rule of law have left lasting damage (Bloom and Hudson 2023).

Foreign interference

Russia, with its imperial ambitions, poses additional risks through foreign interference. It exploits the flaws of the current democratic system and people’s feelings of disillusionment to destabilize democratic processes and institutions. It does so by largely similar means as those used by internal actors seeking power capture: manufacturing disinformation; fueling division, polarization, and distrust; and supporting anti-democratic movements (Morkunas 2022; Wenzel et al. 2024; Bilal 2024). In Western Balkans, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, China exerts influence through strategic investments, strengthening ties with political and business elites and quietly contributing to democratic erosion by nudging the alignment of national policies with authoritarian practices, downplaying human rights violations (Karásková 2022).

Democratic erosion

Democratic erosion in the region stems from the failure to adapt institutions and decision-making methodologies to new global challenges. This is very much a broader problem across democratic societies. The lack of imagination and the rigid association of democracy with electoral representation has stifled innovation and limited opportunities for citizen participation, further exacerbating feelings of powerlessness.

Weaknesses

The region has undergone a paradigm shift away from communist regimes over the past three decades, implementing reforms and building democratic institutions, although to varying levels of success. However, the past—including legacies of violent conflict in the case of the Western Balkans—has left fragility in most of the region that make democratic systems more vulnerable.

The institutional challenges are associated with the relatively young nature of democratic institutions and the presence of corruption, which make it easier to undermine the democratic architecture of the countries in the region.

Behavioural challenges are important too. A sense of lack of agency in citizens couples with an elite-led, hierarchical, and rigid political culture, two mutually reinforcing dynamics that can be traced back to the experiences of living under illiberal regimes that denied civic rights, and perpetrated mistrust, domination and submissiveness (Nova 2019; Maercker 2023). This learned helplessness discourages people from stepping into their role as citizens with rights and responsibilities in a democratic system. People are still learning to trust one another, to hold their governments accountable, and to embrace their own agency.

Strengths

Nonetheless, grounded in values of liberty and self-determination, there is a significant openness to innovation, and the ambition to make up for the years lost, demonstrated by incredible progress over the past three decades throughout the Central and Eastern European region. Lived experiences and the recent history of oppression as well as the geopolitically unstable nature of the neighborhood has instilled a kind of wisdom and alertness to attempts of undue influence among the populations. Although not always easy to act upon, it is a significant and hard-earned strength, and a connector in solidarity with other countries on the same path.

Eastern Europeans show a strengthening interest in citizen participation. This is evidenced by growing engagement in new, adaptable forms of civic activism, which are more informal, more dynamic and ad hoc. These often focus on local issues (Pietrzyk-Reeves et al. 2022).

Civil society, with academia playing an important role, has a strong record of organising and resistance movements. These catalysed independence movements and signify people’s capability to mobilise and stand up and take action against threats to their self-determination and democratic institutions that guarantee it.

How citizens’ assemblies are an important part of the solution

Governments and civil society all over the world are looking for ways to respond to the negative tendencies listed above. Citizens’ assemblies and other forms of citizen deliberation are increasingly initiated to provide citizens with opportunities to take part in public decision making, grapple with complex policy issues, listen to one another, deliberate and find common ground. The OECD has identified a “deliberative wave” of over 700 examples of citizens’ assemblies on all levels of government (2020; 2023).

Citizens’ assemblies, or representative deliberative processes, are groups of people selected by lottery, demographically stratified to be broadly representative of society, brought together to learn and deliberate for a significant amount of time and develop shared recommendations on a policy issue (Curato et al. 2021; Elstub et al. 2019; OECD 2020). With a far-reaching history, they are rooted in ancient Athenian practices and underpinned by the normative principles of deliberation developed by Habermas (1981).

There are two elements that make citizens’ assemblies different from other methods of citizen participation: sortition and deliberation.

Sortition

Assembly members are selected by lottery to be broadly representative of a community, which means everyone has an equal chance to be selected to represent others. The selection process, called sortition, takes place in two stages. In the first stage, a large number of invitations are sent out to a group of people chosen completely at random. Among everybody who responds positively to this invitation, a second lottery takes place to ensure that the final group broadly represents the community in terms of gender, age, geography, and socio-economic differences (DemocracyNext 2024). This is known as stratification.

Selecting assembly members this way has multiple benefits. As sortition intentionally brings together a highly diverse group of people, it maximizes cognitive diversity: research has shown that such diversity is more important than the average ability of a group when it comes to developing solutions and ideas (Landemore 2012). It also ensures reaching and bringing in people who normally do not take part in decision-making, making governance more inclusive and much more representative of the diversity of the population compared to open processes where everyone can join (usually those with the time and confidence to sign up) or elections (where those with resources have more chance to run for office and be elected).

Deliberation

Deliberation means weighing evidence and considering a wide range of perspectives in pursuit of finding common ground. It is distinct from debate, where the aim is to persuade others of one’s own position and to “win”; bargaining, where people make concessions in exchange for something else; dialogue, which seeks mutual understanding rather than a decision; and opinion giving, usually witnessed in online platforms or at town hall meetings, where individuals state their opinions in a context that does not first involve learning, or the necessity to listen to others (DemocracyNext 2024). As a result, deliberation results in considered and actionable public judgements rather than public opinions.

Citizens’ assemblies have been shown to help tackle many of the underlying drivers of challenges to democratic institutions, giving citizens a meaningful say in shaping decisions affecting their lives to counteract the feeling of powerlessness and helping strengthen trust (Knobloch et al. 2019). In doing so, they create the conditions for overcoming polarization as well as for strengthening societal cohesion and democratic resilience. Assemblies also lead to more informed public policy decisions and help policymakers to make hard choices.

To make the most of those benefits, public institutions have begun embedding citizens’ assemblies in a structural way, beyond one-off initiatives that are often dependent on political will (OECD 2021). Permanent citizens’ assemblies are already a reality in Paris, Brussels, Ostbelgien, Bogotá, Ireland, and elsewhere. This move towards a new kind of democratic institutions, based on deliberation and sortition, has been supported by the development of the necessary legal, cultural, and physical infrastructure.

In what ways can citizens’ assemblies contribute to addressing authoritarianism in CEE?

Citizens’ assemblies are beginning to contribute to addressing authoritarianism in CEE. The evidence so far shows that they can help build resilient democratic systems and protect society from malicious techniques that divide and fracture.

Building resilient democratic systems

A resilient democratic system is one that is able to cope with, survive, and recover from complex challenges that can lead to systemic failure (Sisk 2017). Resilient democratic systems are based on strong, accountable relationships between citizens and government. This means developing a deeper partnership where citizens feel a stronger sense of agency and have a recognized value within a political culture. Citizens' assemblies offer a structured and evidence-based approach to meaningfully involve citizens into decision-making that yields useful, actionable recommendations and rewarding experiences for both citizens and governments. They can help rebuild the fractured relationship between citizens and government in the following ways:

1) Strengthening citizens’ agency

Citizens’ assemblies and juries strengthen citizens’ agency—an essential line of defence against internal or external threats to democracy. A strong sense of citizen agency is critical for any democracy to hold officials accountable.

Citizens’ agency, which is often referred to as political efficacy, consists of external efficacy, the sense that public authorities listen to citizens and that citizens have ways to take part in decision-making, and internal efficacy, the belief in one’s capability to be politically active and impact public decisions (Niemi et al. 1991). Meaningful agency entails a civic-mindedness that carries with it deeply felt ownership rights and responsibilities.

In much of the region, many decades of oppression and illiberal regimes and the ensuing violation of human rights has seeded an underlying sense of helplessness and disengagement from the political system. In recent years, that sense of agency has been slowly recovering. An example of this is the extraordinary outpouring of support for Ukraine from everyday people. People in the region have welcomed millions of fleeing civilians and mobilized to crowdfund millions of euros. In Lithuania, the civic empowerment index—measuring civic activeness, potential civic activeness, conception of civil society’s influence, and civic activity risk assessment—has been gradually increasing over the past 17 years (Petronytė-Urbonavičienė et al. 2024).

However, significantly more opportunities for citizens to step into an active role and embrace and exercise their agency are needed to foster those internal beliefs, behaviors, and skills. Citizens’ assemblies are spaces designed for people to deliberate, work collectively with others, and take on the responsibility to shape decisions affecting their lives and the lives of others in their communities. They provide genuine opportunities for citizens to exercise their agency, develop democratic skills, and own their role as citizens in the democratic system. People taking part in a deliberative process have shown increased interest in political life and engagement in it (Felicetti et al. 2016). Recent research on climate assemblies has shown that assemblies can generate sustained forms of political agency during and after the assembly takes place (Boswell et al. 2023) and demonstrate citizens’ assemblies substantial positive effect on political trust, internal and external political efficacy, and political participation among assembly members (Wappenhans et al. 2024).

In authoritarian contexts where lack of trust and legitimacy in the government has rendered the possibility of government initiating citizens’ assemblies unlikely, civil society organized assemblies can be (and have been) used to strengthen a critical, contestatory public sphere, as well as civic agency. In Serbia, academia has been promoting citizen deliberation as a way to carve out the space for democratic practice.

Increased sense of agency can benefit not only those taking part in the assembly, but also those who have heard about an assembly taking place (Knobloch et al. 2019). To encourage this, it is important to ensure broad and effective communication about them amongst the public.

2) Modeling a cooperative political culture

Citizens’ assemblies introduce and model a horizontal and cooperative political culture. A horizontal and cooperative political culture plays an important role in distributing power more evenly and poses a structural challenge to internal power capture, thus enhancing democratic resilience.

Elite-led, hierarchical, merit-based, and rigid political cultures that dominate many societies across the world are present in Central and Eastern Europe (Schwartz1997; Martini 2014). In such cultures those in power exercise a sense of control and superiority, unwilling to give up some of their authority and admit their limitations to consider a more horizontal and cooperative way of taking decisions. This prohibits the development of a more partnership-based society where institutions and structures support relations based on mutual benefit, respect, and accountability (Eisler et al. 2019). Elite-led, hierarchical political cultures send a message to citizens that they are not valuable actors in the democratic system, and their role is limited to casting their vote once every four years. They are also much more prone to power capture as they are less open, transparent, and accountable, and power is concentrated in the hands of a few (Martini 2014).

Citizens’ assemblies are a horizontal decision-making model that aims to maximize inclusion, where cognitive diversity and collective intelligence are emphasized. Because of the random selection of assembly members, where everyone has a largely equal chance of being selected, they send a message that everyone is worthy and capable of taking part in taking decisions that affect their communities. They are designed for finding common ground rather than adversarial domination, or a winner-takes-all approach.

Transitioning to a more open and cooperative political culture can be difficult, especially in countries where lived experiences of authoritarian or totalitarian rule are present and many in the political class have been trained and shaped by illiberal systems. Gradually introducing citizens’ assemblies can model a horizontal and cooperative political culture as an alternative and develop the skills needed to practice it.

3) Enhancing transparency

Citizen deliberation can enhance transparency and strengthen the integrity of public decision-making. This reduces opportunities for individuals with money or power to exercise undue influence. It also helps alleviate corruption, a legacy of the informal networks inherited from communist times in most of the region, that remains a weak spot enabling internal and external power capture.

One of the main benefits of citizens’ assemblies lies in obstructing elite power capture at critical junctures; for example, assemblies could take on an oversight task that creates fewer opportunities for elite manipulation (Bagg et al. 2024). Selection by lottery serves as an effective barrier against corruption as it is much easier for interest groups to exert pressure (or use incentives such as campaign financing) on elected officials with whom they have long-term relationships rather than on randomly-selected citizens who are difficult to identify and who only serve for a limited time.

Even though it requires comprehensive systemic change, citizens’ assemblies can be seen as part of the answer to addressing corruption as they can help strengthen institutional accountability and democratic mechanisms.

Protecting from techniques that divide and fracture

The other major way citizens’ assemblies could contribute to addressing authoritarianism in Central and Eastern Europe is by helping protect societies from techniques employed by malign actors and forces intended to disinform, fuel divides, and cause fracture. Citizens’ assemblies could be used strategically to constructively address potentially divisive issues in an inclusive and informed way before they get weaponized and cause too much harm. Attempts to undermine support for democratic governance, weaken democratic institutions, and portray democratic order as weak, unsustainable, chaotic, and unfeasible can be diffused through citizen deliberation the following three ways:

4) Preventing weaponization of thorny issues

Citizens’ assemblies could be just what is needed to defuse rising tensions where polarization is growing. By establishing them on pressing and divisive issues, governments and civil society could reduce the possibility of a thorny issue being weaponized by populist elites to entrench social divides for their political benefit—a classic move in the populist playbook (Temelkuran 2019)—and protect democracies from internal division and fracture.

Employing assemblies in such a way can create an opportunity for citizens to tackle thorny issues in a constructive way, to promote considered judgement, and to enable them to work toward a shared consensus. Research suggests that when citizens with populist views take part in assemblies, they turn out to be equally motivated by the common good as other citizens (Jacobs 2023). Echo chambers that intensify polarization do not operate in deliberative conditions. Assembly members become less extreme as deliberation reduces biases in information processing and reasoning (Grönlund 2015). Assemblies create the conditions to bridge across differences and construct a shared sense of reality under circumstances where tension is building up and it seems like there is no room for discussion.

5) Safeguarding against mis/disinformation

Informed citizen deliberation could, to some extent, mitigate mis/disinformation, which is routinely employed as a tool of foreign interference to cause polarization and mistrust in fellow citizens as well as government and creates a favorable environment for populist powers to gain prominence. Resilience to mis/disinformation is central to protecting the integrity of democratic processes such as elections and referendums in any democracy.

In citizens’ assemblies, people are presented with diverse stakeholder views and a comprehensive package of information about a specific policy issue. They are invited to think critically and to deliberate extensively over different arguments to develop their own point of view. As the information they receive is made public and communicated widely, this broad base of evidence can also enable informed public debate on the policy issue and reduce the impact of mis/disinformation about the particular issue in society.

Some deliberative processes are specifically designed for this purpose. Multiple Citizens’ Initiative Reviews in both Oregon, the USA, and Switzerland have been set up with the aim of providing information about a specific policy issue to the public. Randomly-selected citizens were brought together to review evidence relevant to an upcoming ballot measure and developed a voter’s pamphlet with verified arguments for and against the proposed measure. The pamphlet was then distributed to all voters to help them take an informed decision.

Citizens’ assemblies can foster a more critical and discerning public discourse. There is evidence suggesting that taking part in a citizens’ assembly reduces assembly members' receptiveness to conspiracy theories, especially when multiple political parties are present at the assembly (Wappenhans et al. 2024).

However, in contexts where misinformation is actively promoted internally by political elites via government-controlled media, such benefits are less likely to be achieved.

6) Strengthening democracy at the local level

Organized by local authorities, academia, or civil society organizations, local level citizens’ assemblies can contribute to spreading political literacy among citizens and create local spaces for democratic politics to develop. Strengthening local governance is often the last line of defence against democratic backsliding, with cities in particular being natural opponents of authoritarianism.

Where democracy is already in serious decline and democratic institutions at the national level are captured and in the process of being dismantled, such as in Hungary and Serbia, citizen deliberation at the local level could present an opening.

This has already been the case in Poland and Hungary, where activists have been responding to democratic backsliding and the shrinking of the public space by implementing citizens’ assemblies with the aim of promoting democratic ideals and reclaiming decision-making from the bottom up (Pospieszna et al. 2022). In most contexts, be they more democratic or less, local level issues are closest to people’s everyday lives and citizens’ assemblies have been extensively used to tackle them, with 52% of all assemblies worldwide taking place at the local level (OECD 2020).

Democracy happens not only at the national level but also locally, and it is a daily practice. Having opportunities to develop and uphold democratic values and norms locally makes a difference and strengthens democratic capital.

Citizens’ assemblies in Central and Eastern Europe

A “deliberative wave” is rising in the region

Evidence shows that since 2016, a “deliberative wave” of 40 deliberative processes has been building up in Central and Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans, and is gaining traction in 2024-2025, with at least 12 deliberative processes underway or planned.

Inspired by the experience and learnings of examples across the globe, policymakers and civil society organizations are demonstrating that citizens’ assemblies are well suited to the region and adapt well to the Central and Eastern European context. In many contexts, citizens’ assemblies took place after a crisis or when a complex problem needed to be solved: for example, the 2016–2018 Irish citizens’ assembly addressed the impasse faced by parliament to amend the constitution and permit abortion. This demonstrates the applicability of assemblies to difficult situations and by extension to societies in transition, further highlighted by the recent interest in assemblies in CEE.

New countries implementing citizens’ assemblies

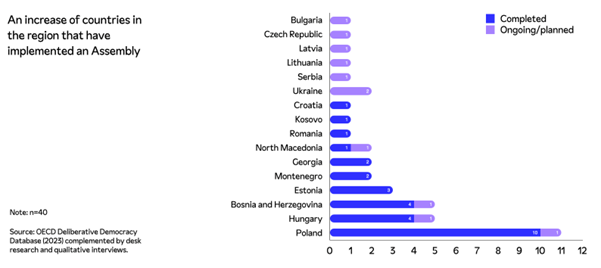

The years 2024 and 2025 will see a doubling of countries in the region that have implemented at least one deliberative process. Ten of them—Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland and Romania—have already implemented citizens’ assemblies or juries, whereas six, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine have all been working on planning or implementing their first assemblies at the time of writing this study. This substantial increase of interest suggests that the first examples have been successful. It also highlights the opportunity for and importance of promoting good practice principles and high democratic rigor for upcoming citizens’ assemblies as they gain traction in the region.

Local government is leading the way

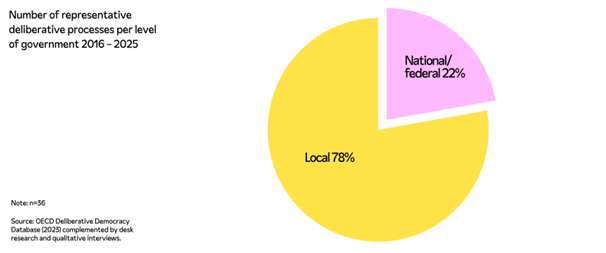

Most of the examples collected have taken place at the local level (78%), whereas 22% took place at the national level. In some contexts, for example in Hungary, local assemblies are the only possibility as municipalities become bastions of democracy when democracies at the national level are eroding. These numbers can also be explained both by the strategic choice of first piloting representative citizen deliberation on lower stakes local-level issues that are closer to people’s everyday lives and, simply, more options for initiating assemblies being at the local level given the number of municipalities compared to national level institutions. Local-level processes are usually less resource intensive. For example, Poland, a clear leader in the region, has almost exclusively focused on local assemblies, with efforts towards a national level coming much later.

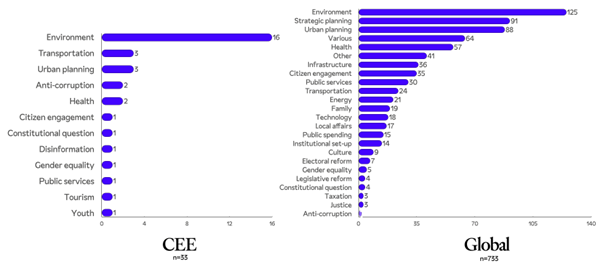

Environment is the most popular issue

Citizens’ assemblies and juries have tackled a range of different issues. The environment has been the most popular issue, addressed by a total of 16 citizens’ assemblies so far. This tendency is in line with the global trend captured by OECD data in 2023, demonstrating the environment overtaking urban planning as the most popular choice of issue, making up 17% of all assemblies. In attempting to tackle the global challenge of climate change, public authorities are looking for new ways to tap into citizens’ collective intelligence and find creative solutions. The Knowledge Centre on Climate Assemblies (KNOCA) has found that climate assemblies can challenge social and climate inequalities, make climate policy stronger, break political deadlocks on climate action, and create spaces to constructively address complex and multifaceted issues that affect everyone (2024).

It is interesting to note that disinformation (tackled in Montenegro’s two assemblies) and anti-corruption (addressed in the Kosovo citizens’ assembly) are among issues tackled in the region, which are not common choices globally and reflect regional specificities.

Starting smaller and shorter

On average, deliberative processes have taken four days (ranging from two to six days) and brought together 53 assembly members (ranging from 33 to 90 members). This demonstrates that, so far, shorter and smaller to mid-length processes have been prioritized, while national level assemblies spanning across multiple months remain to be organized in the future. The choice of shorter, local processes is also tied in with first testing out citizen deliberation on a smaller scale and with limited resources available.

European institutions lead in funding assemblies

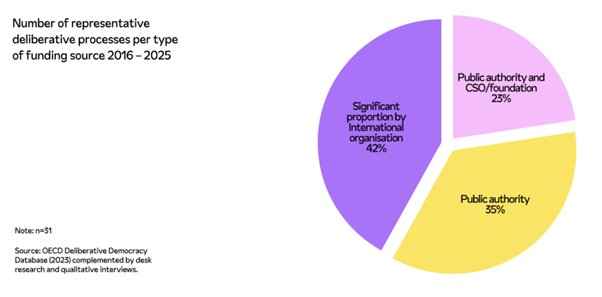

Overall, most deliberative processes in Central and Eastern Europe have had mixed sources of funding. Almost half (42%) of deliberative processes have benefited from significant financial contributions by international organizations. This is the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, and North Macedonia. Around one-third (32%) of assemblies were predominantly funded by public authorities (largely in Estonia, Hungary, and Poland). Finally, 26% were funded by public authorities together with civil society and foundation contributions (Croatia, Georgia, Lithuania).

Estonia, Hungary, and Poland are the pioneers of deliberative democracy in the region. Some local government funding for citizens’ assemblies has been achieved after years of demonstrating their value. In Estonia, efforts are put towards securing a dedicated public budget for new forms of democracy.

The data also shows a substantial dependency of democratic innovations in the region on international organizations, particularly on European institutions. Funding comes from the programs of European Parliament Democracy Support and Election Coordination Group, the Council of Europe, European Commission DG REGIO, and Horizon Europe.

Having European institutions involved in funding and overseeing deliberative processes in countries where trust among citizens and governments is low lends credibility to the process in the eyes of citizens and civil society organizations and is a welcome step. However, significant reliance on European funding for citizens’ assemblies highlights that there is more work to do in the region to maximize and publicize their benefits. The goal, over time, must be to build sustainable funding sources that are local to build assemblies into durable democratic institutions.

Challenges and coping strategies

Interviews with practitioners advocating for and running citizens assemblies in the region have uncovered several contextual challenges to citizens’ assemblies but also shed light on the remarkable resilience and adaptability as well as creative approaches they have taken to mitigate them.

Securing political will and commitment in hierarchical and elite-driven political culture

Unsurprisingly, as citizens’ assemblies are governance models that in many ways contrast with hierarchical, elite-driven governance structures and political culture, securing the political will and commitment to implement them is a challenge.

"It is just so deeply rooted, our attitude towards public affairs, and we do not have that political culture that our colleagues in Western Europe operate in, where discussions are more open and everybody feels they have the right to be engaged in all kinds of discussions"—assembly organiser in CEE

"Our societies are more elite driven, because if you think back to the transition period, it was an elite driven transition. So the social structures have been shaped by are still largely driven by elites, which discourages open discussions people’s involvement"—assembly organiser in CEE

This manifests in a lack of institutional frameworks and incentives to involve citizens in public decision-making, as well as public officials perceiving citizens as a risk to be managed rather than valuable members of the democratic system that can help make better policy decisions. Such beliefs have been exacerbated by the unhelpful design of some of the other forms of citizen participation and engagement, such as town hall meetings or purely informative public consultations, that lead to confrontational, unconstructive or unhelpful interactions between citizens and governments. This is a tendency experienced globally; however, it is comparatively more pronounced in Central and Eastern Europe. The OECD Trust survey has found that among member countries, respondents from CEE had the lowest perceived likelihood that the political system allows people to have a say in what the government does, with less than 20% of people finding it likely (2024).

Despite these challenges, practitioners have developed strategies to secure political will to organize assemblies and institutional commitments to take up their recommendations. These include identifying democratic champions—motivated individuals in the government—that sponsor and enable assemblies to happen. For example, a newly created team of advisors to the chief architect of Vilnius, Lithuania, has been responsible for advocating for the first citizens’ assembly in the city among colleagues and councillors, forging new connections internationally and seeking support to run it.

Perceived legitimacy of citizen deliberation and “participation-washing”

There is a low baseline of trust in institutions amongst citizens, in part due to the presence of corruption in most of the region (OECD 2021). This mistrust is especially present between organized civil society and the government, often leading to confrontational relationships. This creates a challenge as a government and civil society partnership is often needed to implement a citizens’ assembly, along with a mutual recognition of the value the process has.

This widespread mistrust can make it difficult to organize citizens’ assemblies that would be trusted by citizens as legitimate processes with positive intentions. This is a reasonable concern, as citizens’ assemblies should be implemented with the knowledge that like any other part of the democratic system, they are not immune to influence or misuse by a government to legitimize its decisions. Usually, clear and transparent governance and protocols for citizens’ assemblies, as well as independent evaluation, helps ensure their legitimacy and democratic quality. But in contexts where civil society and the rule of law are compromised, these checks and balances might not always be possible, especially at the national level. The presence of international observers or deliberation in frameworks organized by international organizations could address such concerns.

"We have a high level of corruption in politics, and people don’t trust the government. So that's why when you involve a partner with a strong reputation, like the European Parliament, the people who are involved trust the process much more. It doesn't have to be money, but as we work to gain trust from citizens, we need somebody to help us."—assembly organiser in CEE

For this reason, many of the assemblies in the region, especially in the Western Balkans, have involved European institutions or were first initiated by universities to lend their credibility and ensure transparency during the process.

Limited resources and capacity

An important limitation to organising citizens’ assemblies in Central and Eastern Europe is the lack of resources and capacity. There is often a lack of financial support from local governments and institutions, and many assemblies rely heavily on external funders, such as the European Parliament, the Council of Europe, and various NGOs. This dependence can complicate the sustainability of long-term initiatives. The costs associated with organizing assemblies are further exacerbated by limited organizational capacity in the region, with not enough organizations possessing the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively deliver assemblies, something that often needs to be addressed by hiring expensive international experts. This combination of factors poses a risk to the scalability and quality of assemblies in the region.

To overcome these issues, several strategies have been adopted. One recent approach has been the pairing of assemblies, where two are run simultaneously with coordinated efforts to save funds and share capacities. This was the case when running assemblies in Mostar and Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2024. Designing and running both assemblies simultaneously helped cut down on the time and costs, and allowed the organizers to transfer lessons learned, skills and expertise.

Additionally, there is a growing emphasis on the importance of sharing experiences and lessons learned amongst organizers in the region. International partners have been a valuable resource, providing support and expertise—but building local expertise has been crucial to foster sustainable, locally driven initiatives.

How can the impact of assemblies be amplified in the region?

Resources and knowledge

Improving access to resources to run citizens’ assemblies and building the capacity for more local civil society organizations to have the knowledge and expertise to do so would amplify the benefits that citizen deliberation can bring and would capitalize on the momentum and interest now present in much of the region.

Ensuring quality

These first examples of citizens’ assemblies in the region have the opportunity to demonstrate the potential and benefits citizen deliberation can bring to decision-makers and broader society. High quality processes are a prerequisite also because there are real risks of undue influence in some of the hybrid regimes and poorly-designed assemblies and juries can lead to co-option or misuse. Promoting high quality assemblies that meet quality standards, such as the OECD good practice principles, and evaluating them to capture learnings helps to ensure their democratic rigor and neutrality, as well as build trust in their outcomes. These standards include ensuring assemblies are consequential, their governance transparent and accountable, and that they create the necessary conditions for quality deliberation.

Systemic change

As part of a growing trend to maximize the benefits of citizens’ assemblies, in Paris, Brussels, Bogotá and elsewhere they have been embedded into the system of democratic decision-making in an ongoing way. This means that rather than being one-off initiatives dependent on political will, they become a normal part of how certain types of decisions are taken, often with a legal or institutional basis underpinning their connection to existing institutions like parliaments. More assemblies provide more opportunities for more people to represent others, ultimately giving people more power in shaping decisions. This would also allow public decision-makers to get better at making difficult decisions (OECD 2021) and help develop more resilient democratic systems.

Infrastructure for deliberation

To make it possible to run assemblies more easily and cost-effectively, and with fewer legal and administrative challenges, there is a need to develop supporting legal, administrative, physical, and technical infrastructure across the region. This could mean implementing paid participation leave, knowledge-sharing networks among policymakers, practitioners, and academics who initiate, run, and study assemblies, and easier access to data required to run random selection.

Conclusion

The “deliberative wave” gaining momentum in Central and Eastern Europe, and paints a hopeful picture. Forty assemblies and counting since 2016 shows that citizens’ assemblies and juries can, and have been, successfully implemented in contexts with a recent history of illiberal regimes. Public authorities and civil society are growing increasingly curious about the potential of citizens’ assemblies and opening up to trying them as part of the solution to the democratic challenges they face. Citizens are taking up this invitation, one letter at a time.

Implemented well and more systematically, citizen deliberation has started contributing to a more democratic future for Central and Eastern Europe and could present a substantial democratic response to authoritarianism in the region. It can do so in two ways: by building more resilient democratic systems and by protecting from techniques that divide and fracture. This can be true even in illiberal contexts, where assemblies have a different role of opening up a critical, contestatory public sphere, and strengthening civic agency.

Even though contextual challenges to citizens’ assemblies persist, such as difficulty to secure political will, limited perceived legitimacy as well as limited resources, overall, the remarkable resilience and adaptability of the region presents a fertile ground for democratic innovation and uptake of citizens’ assemblies.

As Turkish writer Ece Temelkuran has said, autocrats want us to believe we are powerless, and that belief is dangerous. Multiplying constructive opportunities for citizens to exercise collective agency and realize their power is the antidote to autocracy.

References

Anghel, Veronika, and Erik Jones. 2024. “What Went Wrong in Hungary.” Journal of Democracy 35, no. 2: 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2024.a922833

Bagg, Samuel. 2024. “Sortition as Anti-Corruption: Popular Oversight against Elite Capture.” American Journal of Political Science, no. 68: 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12704

Bechev, Dimitar. 2024. “Serbia’s authoritarian (RE)turn - Carnegie Europe.” Accessed 6 August, 2024. https://carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2024/01/serbias-authoritarian-return?lang=en

Bilal, Arsalan. 2024. “Russia’s hybrid war against the West, NATO Review.” Accessed 6 August, 2024. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2024/04/26/russias-hybrid-war-against-the-west/

Bloom, Emily and Alexander Hudson. 2023. “Is Poland’s Democratic backsliding over? History shows it takes more than an election.” International IDEA. Accessed 6 August, 2024. https://www.idea.int/blog/polands-democratic-backsliding-over-history-shows-it-takes-more-election

Boswell, John, Rikki Dean and Graham Smith. 2023. “Integrating citizen deliberation into climate governance: Lessons on robust design from six climate assemblies.” Public Administration 101, no. 1: 182–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12883

Calderon de la Barca, Laura, Katherine Milligan, and John Kania. 2024. “Healing Systems.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://doi.org/10.48558/EZE7-CM71

Cameron, Rob. 2024. Slovakia’s populist government to replace public broadcaster. BBC News. Accessed 6 August 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68887663

Cesnulaityte, Ieva. 2023. “Democratic Innovation: A Matter of National Security.” IWMpost. (Vienna, Austria)

Christakis, Nicholas A. 2019. Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society. Little, Brown and Company.

DemocracyNext. 2023. “Assembling an Assembly: A how-to guide.” https://assemblyguide.demnext.org/

Dryzek, John S. 2005. “Deliberative Democracy in Divided Societies.” Political Theory 33, no. 2: 218–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591704268372

Eisler, Riane, and Douglas P. Fry. 2019. Nurturing Our Humanity: How Domination and Partnership Shape Our Brains, Lives, and Future. Oxford University Press.

Edelman. 2023. Edelman Trust barometer 2023. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2023/trust-barometer

Elstub, Stephen, and Escobar, Oliver. (Eds.). 2019. Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. Accessed August 6, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433862

Felicetti, Andrea, Simon Niemeyer, and Nicole Curato. 2016. Improving deliberative participation: Connecting mini-publics to deliberative systems. European Political Science Review 8, no. 3: 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773915000119

Fiket, Irena, Čedomir Markov, Vujo Ilič, and Gazela Pujar Draško. 2024. Participatory Democratic Innovations in Southeast Europe: How to Engage in Flawed Democracies. New York: Routledge.

Gailiene, Danutė. 2008. Ką jie mums padarė. Tyto alba. (Vilnius, Lithuania)

Grönlund, Kimmo, Kaisa Herne, and Maija Setälä 2015. “Does Enclave Deliberation Polarize Opinions?” Political Behavior 37, no. 4: 995–1020.

Guriev, Sergei, and Daniel Treisman. 2020. A theory of informational autocracy. Journal of Public Economics, no.186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104158

Hickman, Caroline, Elizabeth Marks, Panu Pihkala, Susan Clayton, R. Eric Lewandowski, Elouise E. Mayall, Britt Wray, Catriona Mellor, and Lise van Susteren. 2021. “Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey.” The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12): e863–e873. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00278-3.

Hübl, Thomas. 2020. Healing Collective Trauma: A Process for Integrating Our Intergenerational and Cultural Wounds. Boulder, CO: Sounds True.

Jacobs, Kristof. 2023. “Populists and citizens’ assemblies: Caught between strategy and principles?” De Gruyter Handbook of Citizens’ Assemblies, edited by Min Reuchamps, Julien Vrydagh and Yanina Wel. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter,. 349-364. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110758269-028

Kapidžic, Damiŕ. 2020. “The rise of illiberal politics in Southeast Europe.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 20, no. 1: 1–17. doi: 10.1080/14683857.2020.1709701

Karásková, Ivana. 2022. CEPA. Chinese Influence in the Czech Republic. https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/chinese-influence-in-the-czech-republic/

Knobloch, Katherine R., Michael L. Barthel, and John Gastil. 2019. “Emanating Effects: The Impact of the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review on Voters’ Political Efficacy.” Political Studies, no. 68: 426–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719852254

Knowledge network on climate assemblies. 2024. KNOCA. https://www.knoca.eu/

Krastev, Ivan, and Mark Leonard. 2024. “A crisis of one’s own: The politics of trauma in Europe’s election year.” ECFR. Accessed 6 August, 2024. https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-crisis-of-ones-own-the-politics-of-trauma-in-europes-election-year/

Landemore, Hélène. 2012. Democratic Reason: Politics, Collective Intelligence, and the Rule of the Many. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Landemore, Hélène. 2022. Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century. Princeton, New Jersey; Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism. Cambridge University Press.

Mate, Gabor. 2022. Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture. Avery Pub Group.

Maercker, Andreas. 2023. “How to deal with the past? How collective and historical trauma psychologically reverberates in Eastern Europe.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, no. 14: 1228785. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1228785

Martini, Maíra. 2014. “State Capture: An Overview.” Transparency International. https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/helpdesk/State_capture_an_overview_2014.pdf

Morkūnas, Mangirdas. 2022. “Russian Disinformation in the Baltics: Does it Really Work?” Public Integrity 25(6): 599–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2092976

Niemi, Richard G., Stephen C. Craig, and Franco Mattei. 1991. “Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 national election study.” American Political Science Review, 85(4): 1407–1413.

Nord, Marina, Martin Lundstedt, David Altman, Fabio Angiolillo, Cecilia Borella, Tiago Fernandes, Lisa Gastaldi, Ana Good God, Natalia Natsika, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2024. “Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot.” University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute.

Nova, Eszter. 2019. “The Role of Fear and Learned Helplessness in Authoritarian Thinking.” International Relations Quarterly, ISSN 2062-1973, 10(3-4).

OECD 2020. “Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD 2021. “Evaluation Guidelines for Representative Deliberative Processes.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD 2021. “Eight Ways to Institutionalise Deliberative Democracy.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD 2023. Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions. https://airtable.com/appP4czQlAU1My2M3/shrX048tmQLl8yzdc

OECD 2024. Trust in Government (indicator). doi: 10.1787/1de9675e-en

OECD 2024. OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results: Building Trust in a Complex Policy Environment, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9a20554b-en

Parry, Lucy J. 2023. “‘It’s not my job to engineer you an outcome’: Integrity challenges in deliberative mini-publics.” Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance, University of Canberra

Petronytė-Urbonavičienė, I. et al. 2024. Civic Empowerment Index 2023, Civitas. Accessed 22 August, 2024. http://www.civitas.lt/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/PGI_2022metai.pdf

Pietrzyk-Reeves, Dorota, and Patrice C. McMahon. 2022. “Introduction: Civic Activism in Central and Eastern Europe Thirty Years After Communism’s Demise.” East European Politics and Societies 36, no. 4: 1315–1334. https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254221089261

Pospieszna, Paulina, and Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves. 2022. “Responses of Polish NGOs engaged in democracy promotion to shrinking civic space.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 35, no. 4: 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2022.2027869

Sisk, Timothy D. 2017. “Democracy and Resilience: Background Paper.” IDEA. Accessed 22 August, 2024. https://www.idea.int/gsod-2017/files/IDEA-GSOD-2017-BACKGROUND-PAPER-RESILIENCE.pdf

Solt, Frederick. 2012. “The Social Origins of Authoritarianism.” Political Research Quarterly 65, no. 4: 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912911424287

Schwartz, Shalom H., and Anat Bardi. 1997. “Influences of Adaptation to Communist Rule on Value Priorities in Eastern Europe.” Political Psychology 18, no. 2): 385–410.

Svolik, Milan W. 2023. “In Europe, Democracy Erodes from the Right.” Journal of Democracy 34, no. 1: 5–20. Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2023.0000.

Temelkuran, E. 2019. How to Lose a Country. Harper.

Wappenhans, Tim, Bernhard Clemm von Hohenberg, Felix Hartmann, and Heike Klüver. 2024. “The Impact of Citizens’ Assemblies on Democratic Resilience: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” OSF Preprints. July 24. doi:10.31219/osf.io/hnp8k.

Wenzel, Michał, Karina Stasiuk-Krajewska, Veronika Macková, and Katerina Turková. 2024. “The penetration of Russian disinformation related to the war in Ukraine: Evidence from Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” International Political Science Review 45, no. 2: 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121231205259

This publication represents the views of the author(s) and not the collective position of the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM Vienna) or the “Europe’s Futures” project.