ANASTASIA PLATONOVA: What is the "imperial gaze" you write about?

EWA THOMPSON: The imperial gaze is a set of views, prejudices, and intentions that countries with a colonial perspective use in their interactions with other nations—especially those they have historically influenced or once controlled.

What distinguishes this perspective? It is not merely the presence of certain beliefs or ideology but an inherent—and often aggressive—desire to impose them on others, presenting them not as a personal viewpoint but as the only possible reality. This involves significant manipulation of facts, distortion of concepts, propaganda, and more.

This perspective often claims: “We did not simply conquer and subjugate these countries. They were underdeveloped, and we brought them education, prosperity, and economic growth.” In reality, however, there was no true "missionary" aid. On the contrary: empires simply extracted natural, human, and other resources from the territories they controlled under the guise of a “big brother” fostering development, all while destroying or erasing their identities and justifying their actions in the process.

The imperial gaze is truly harmful—and even lethally dangerous—not only for the countries subjected to it but for the entire world. It creates numerous imbalances, ranging from political and economic disparities to imbalances in global knowledge, where some nations wield significant influence at the expense of others.

There have been many former empires, but most of them eventually "grew up," letting go of their former colonies. Russia, however, is the exception—rather than moving forward, it still seeks to be an empire in the 21st century, expanding its territory by force. What does this tell us?

We should not idealize former empires. They, too, have a history full of actions they should not be proud of. However, history has largely followed a path where rationality and justice prevailed, leading most empires to eventually relinquish their colonies. This happened due to both objective circumstances and internal evolution. At some point, former empires recognized that having, for instance, India as an equal partner in a commonwealth of nations was better than holding it as a colony. And the world benefited from this shift.

Unfortunately, Russia never embraced this evolutionary path. There are several reasons for this. The Western world, to varying degrees, follows global trends and intellectual thought, which suggest that a stable and prosperous world is one made up of free, independent nations that respect each other’s sovereignty and borders. But for Russia, these ideas hold no weight. It is neither deterred by international opinion nor by the threat of political and economic isolation—it spent much of the 20th century in isolation and continues on that path today. Russia’s political elite, along with much of its population, has long believed that Russia is a "world unto itself," capable of thriving in isolation.

Another key factor preventing Russia from transitioning from an empire into a modern European nation is geography. Many indigenous peoples, particularly in Siberia, were physically unable to defend themselves against Russian imperial expansion. At the same time, their lands held vast natural resources, further fueling Russia’s imperial ambitions. The results of these ambitions are evident today—not only in Russia’s enormous territory but also in the many nations living within it, whose resources the state continues to exploit, often without benefiting them in return.

Let us leave geopolitics aside and talk about literature. If we look not only at classical but also contemporary Russian literature, it remains deeply imperial, built around this strange, artificial concept of the "greatness" of Russian culture. In your opinion, what does this indicate?

This, too, is a consequence of Russia’s long-standing isolation—they genuinely do not understand that [others] see things from a completely different perspective.

While Europeans have regarded (and some still regard) Russian culture as worthy of attention, this interest should not be confused with blind admiration. Russian culture is not the center of the universe for Europe. No one here reveres it in the way Russia would like to portray it—as something "great." Rather, it is simply a matter of having a civilized appreciation for the cultures of other nations. But Russians are deeply mistaken if they believe that Europeans see their culture as the world’s most important—this is just another myth, like many others created by Russian propaganda.

That is a very insightful point—Russia itself propagates the myth that the world believes in the greatness of its culture. Why do you think even the best examples of Russian literature almost always contain typical colonial narratives? Why is this always "embedded" in Russian texts?

These colonial, imperial narratives are the very fabric of Russian culture, particularly its literature. It’s important to understand that this mindset took a very long time to develop and become deeply rooted. Naturally, changing this perspective will also take a great deal of time. Unfortunately, even if Russia wanted to change in this regard (which, at the moment, we do not see happening), it would not be as simple as agreeing to it, writing a few good books, or holding a few discussions. When this process begins, it will be incredibly difficult and painful.

Maybe it is time for the world to reconsider its long-standing view of Russia’s cultural icons, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky? Or at least place their works in the context of where they were created and how they continue to function as a form of ideological weaponry?

Well, I have to say that both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are indeed great writers. But aside from that, you are absolutely right—it is always important to challenge established or outdated perspectives, especially those that have long been seen as unquestionable. And for that, not just my book but many more books, studies, and discussions are needed. When we seek to question and encourage a reassessment of ingrained beliefs and views, we need experts—professionals whose knowledge, expertise, and fresh perspectives can help people start to wonder whether Russian literature is truly as "great".

Just as Russians have turned their writers and artists into untouchable idols, Western Europeans have their own cultural figures they hold in similar regard. Even the mere suggestion of reassessing the historical role of some of these figures might meet resistance—even if it is subconscious. That is why both European and Russian culture provide rich material for scholars and researchers who aim to reevaluate and reinterpret works long considered great, even iconic.

You made a very relevant point about researchers, as education is indeed one of the cornerstones. Unfortunately, it has historically been the case that most Slavic Studies departments at international universities are primarily Russian Studies departments. This means that many Western European students study Russian literature. Why is there still such a lack of a critical perspective on it?

This is a very important question. And that is exactly why we need to apply consistent pressure (in the best sense of the word) on international universities to help them fully reinvent their Slavic Studies departments. These departments should be studying the cultures (and specifically the literatures) of various Slavic nations, not just Russian. Russian is far from the only language spoken by Slavic peoples, and Russian culture is by no means "central" to all Slavs.

But it's not just about adding Ukrainian or Belarusian literature alongside Russian literature in universities. No, it is about a complete reevaluation of Slavic Studies departments and the principles they are built on. This process of rethinking needs to be a strong movement involving university administrations and faculty members.

We have talked about the Russians, now let us talk a bit about the Europeans. Why do you think years of Western Europeans reading Russian literature, which is supposed to help understand the mysterious Russian soul, have not really helped them understand what kind of country Russia is?

Perhaps I will sound cynical, but in reality, very few people in Europe care about what happens east of the Oder River. Western Europeans know perfectly well what is happening. However, they are convinced that even if Russia started a war in Ukraine, and even if it were to occupy Belarus, Poland, and the Baltic states, it would stop at the German border. Western Europe really is not all that concerned about what is happening in Eastern Europe. Of course, you will not find any such statements in international media or European politicians’ remarks, but the reality is exactly that.

Of course, Western European countries are helping Ukraine, but they are primarily concerned about themselves (in particular, it matters to them that by fighting in Ukraine, Russia is weakening itself).

And it is not just about Ukraine. A free Poland in Europe, for example, hardly concerns many either. Germany or France know how to defend their borders well, but when it comes to other countries, no one cares about their fate. No one in Europe is going to fight Russia to preserve Ukraine and its sovereignty.

Western European countries are very fortunate to have this belt of states between Germany and Russia, and everything happening there shows us the real state of European security. But of course, no European politician will ever publicly admit this.

At last year's Frankfurt Book Fair, I accidentally stumbled upon a very strange discussion called “Is there hope for Russia?” What do you think, is there hope that Russia will stop seeing itself as an empire? Your book ends on a rather hopeful note, but it was written years ago. Is there hope now?

Oh, what a tough question. I will say this—we at least must hope that there is hope. Because if there is not, we are facing a third world war. So, of course, there is always hope, even if nothing else is left. There is always a chance for change. But let us take another look at history, specifically at what happened with another aggressive conquering regime: Nazi Germany. As we know, the Nazis lost World War II, Berlin was taken by the Allied forces, Hitler committed suicide, and German society went through a difficult process of realizing what an evil the Nazi regime truly was.

I am convinced that something similar will happen with Russia: that this aggressive regime will fall and lose this war (even though Europe is not in a hurry to fight it directly). But there is also a separate part of this change, and it involves Russians themselves changing their thinking and perception regarding Russia’s geopolitical role and its relations with other countries. And right now, we can only hope for that, because the average Russian population does not read books by European intellectuals or engage in discussions like the one we are having now.

For these changes to happen, it is crucial for Russians to look beyond their internal context, to see the broader world, to be able to critically reflect on reality, and so on. And here we return to the isolation I mentioned several times already. Because they really live in their own "bubble," just as most Europeans know about Russia only from the media.

Of course, we need many more books, discussions, and other intellectual efforts to bring about real change. These are important efforts, and they must never stop.

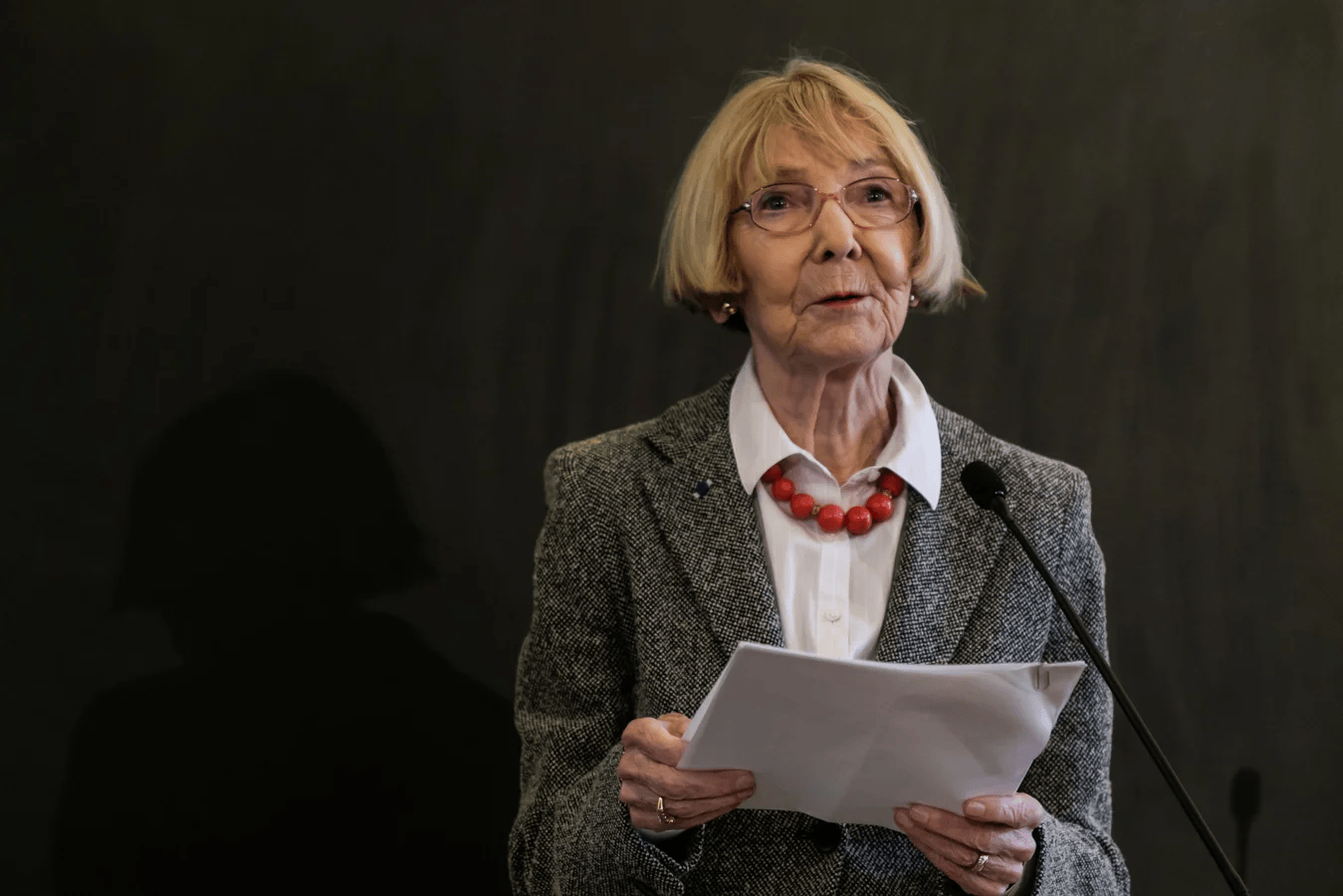

Interview by Anastasia Platonova; Translated by Kate Tsurkan; Photo of Stefano Dal Pozzolo for Fundacja Świętego Mikołaja.

The article was first published in Ukrainian and Polish and came out of the collaboration between the IWM and the Polish online magazine Dwutygodnik.

Ewa Thompson

American literary critic, a Polish-born Slavist researcher, author of the book Troubadours of Empire. She was an invited guest of the X Lviv Media Forum. One Ewa Thompson’s main interests in the study are the source, content, and consequences of imperial motives in Russian culture in different historical periods (XIX-XX centuries).

Anastasia Platonova

Cultural critic, journalist, editor, cultural analyst. Her specialization is criticism of contemporary visual culture and cultural policies. She has experience of cooperation with key Ukrainian cultural institutions and works as a lecturer and cultural expert.