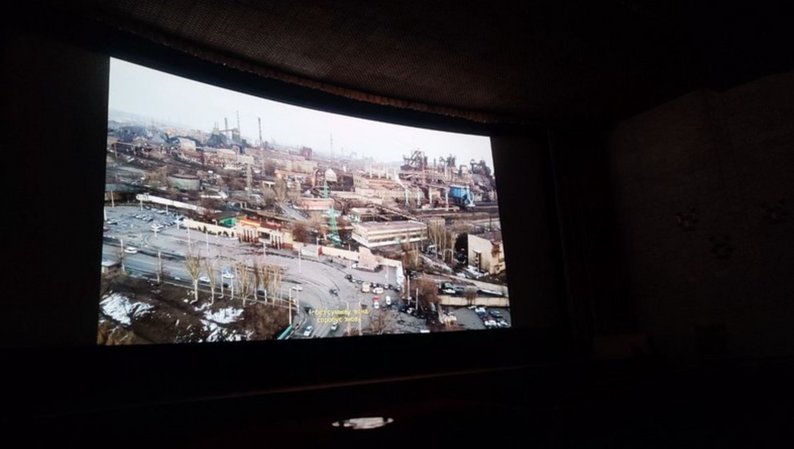

I was afraid to watch 20 Days in Mariupol, not because of what I expected to witness on-screen—death, devastation, and bodies—but because of the prospect of reliving the initial days of the full-scale invasion. I still vividly recall my reaction upon seeing Evgeniy Maloletka's photographs from Mariupol for the first time. My fear stemmed from the idea of being transported back to that moment and having to experience those emotions anew.

This apprehension highlights the struggle we face when trying to evade memories and come to terms with the reality of past and present events. As journalists, your role is crucial in bringing us back to this reality. We have previously talked a lot about the mission of journalists, so I'm curious: What type of journalist do you consider yourself to be, and what do you believe is your mission in covering this war?

It seems to me that I am a humane journalist, or rather, I am a human, not just a journalist. And in this, perhaps, lies my position: to remain human in order to understand and empathize with other people. What did we encounter with the beginning of the full-scale invasion? It was the first time we all went through the shared experience of a horrific war. From small things to major shelling and nights spent in basements. To comprehend all of this, one must feel it oneself. And one must understand what another person feels at that moment. And, of course, we — a team of Ukrainians — felt the same anger that the people around us felt. But in those first days, I just wanted to be there with them and give them a voice.

I remember the moment when we were sitting in the hospital at night during heavy shelling. There was no longer any light, water, or food. There was a woman sitting beside me, and at some point, she started crying. She said, “Nobody hears us, nobody will help us, we will all just die here.” And I replied that they heard her. That they would hear us, help us, and save us. We would keep on living, and everything would be okay, even under such dire circumstances. And it was through our photos, videos, and information that we wanted to shout to the whole world: “Look at what is happening now; it’s like the end of the world!” At that moment, my main mission was to give a voice to these people so that they could be heard and saved.

I later discovered that journalism can directly save lives. Our photos and videos played a crucial role in negotiations among international partners and leaders from various countries to open a safe corridor for people to evacuate from Mariupol. Learning about this afterward was incredibly meaningful for me. Thousands of individuals managed to escape and protect themselves thanks to these efforts. People globally gained insight into the situation unfolding in Mariupol.

Even now, my mission remains unchanged. I have always loved people and always wanted to be there for them, to support them. I wanted to open the eyes of others to the problems that go unnoticed. Because sometimes we can walk down the street and not even know what story lies behind this or that person. I think my most important mission, and indeed that of journalism is to open people’s eyes to societal problems. I constantly receive messages from the heroes of our stories thanking us for this.

It is very important that the memory of the people who are no longer with us always remains alive and becomes a story. And the least that journalists can do is to tell these stories to make sure they aren’t reduced to mere statistics.

How did you come to focus on global societal issues rather than solely focusing on Ukraine? How did you overcome fear when addressing challenging and intricate problems, and how did you learn to communicate about them with others?

I believe I'm quite empathetic. Whenever I'm working on a story or dealing with its subjects, I make sure to see things from their perspective. I think we’ve all experienced that sense of loneliness when facing a problem alone, like when you're just sitting there crying with no one to lean on for support. I’ve always wanted to change that. It’s important for people to know that they’re not alone in their struggles in this world.

I recall a particular incident during my time working on news coverage in Kharkiv. I was assigned to create a report about rare children's diseases, a topic no one else wanted to cover. I attended an event where children with conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy were present. Some of these children don't live past 20 due to heart or lung complications; their heart or lungs stop working. With proper care, they could live to be 40-50 years old, but in Ukraine, such care is expensive and not readily available. I was struck by the fact that life can end when it's just beginning.

The main desire of the children was to learn to ride a bike. At that moment, I thought about how many people do not appreciate what they have. And I also thought about how much we could change if we talked about problems out loud.

I want to fight against this injustice and stand up for people’s rights because everyone deserves to live a happy life. Since the beginning of the war, even more problems have emerged. Every day becomes a matter of life and death. Journalists are constantly in the midst of war. And it is important for us to speak to the whole world so that it hears about people’s stories, the victims of war crimes, and the deaths of adults and children. We must constantly talk about it and seek justice.

When you’re unafraid to address a problem or trauma, or when you’re interested in it, or when you have the capacity to empathize and feel others’ pain, it’s more than just a unique ability. It can also become a heavy burden and harm you in the process. With the escalation of the war, as you mentioned, the scope of these challenges has grown significantly in both numbers and impact. How do you manage to handle such a vast amount of distressing stories and the pain of others?

From the very start of the full-scale war, I made a conscious effort to pull myself together and remain strong. I told myself I wouldn’t be weaker than the guys on my team. They knew firsthand what war was like thanks to their years of experience. Although I lacked this, I resolved to face the situation with dignity. What keeps me going now is witnessing the positive impact on people. Even seeing them smile after our conversations gives me strength. Knowing that I’ve helped someone makes my day meaningful. Helping others has become the purpose of my life—I don’t want to focus solely on myself or ignore what's happening around me.

Do you fear for yourself?

No, I’m not afraid. If I encounter any difficulties while helping someone or telling their story, I won’t feel regret. What’s there to fear? People? Facing the truth? I’m not afraid of those things.

You’re getting up close to all of it?

Yes.

You’re a brave woman. Do you feel like you’re in close proximity to evil and sorrow?

Of course.

What’s your distance?

It seems like death is constantly breathing down my neck.

It’s behind you, right?

Yes, it’s always somewhere nearby.

And human sorrow is in front of you, right?

Yes, basically. Death is always somewhere close. I’ve never attended so many funerals in my life as I do now. It has almost become a daily routine. We film there. There was a time when I went to funerals every day for a whole week.

You’re not running away from death?

No, I understand what’s important to people. When a loved one dies, it’s crucial to honor their memory and to have a story that keeps them alive in our hearts. I just want to give meaning to this, to give publicity to the story of this person, a worthy person, a hero. Because all Ukrainians now are heroes in their own way, fighting for freedom.

I believe 20 Days in Mariupol captures many small yet remarkable moments that occur when people display incredible qualities, like police officer Volodymyr Nikulin, for instance. These moments reveal wonder, humanity, kindness, and beauty. Even in a landscape devastated by destruction, there’s still a glimpse of life amid the apparent signs of death.

One of the film’s strengths is its portrayal of the coexistence of life and death. Despite the looming presence of death, humanity perseveres, showcasing the vitality you mention. We acknowledge the proximity of death, its constant presence, and sometimes its pursuit. Your gripping road movie, an odyssey where each day brings new challenges and escalating situations, juxtaposed with escapes while many others don't make it, symbolizes your journey—an escape from death that, despite immense pain and loss, maintains a thread of hope.

Life goes on always. And there is life after death. We’re only here for a while.

You prolong their lives — those heroes of yours who have died.

Certainly.

They become eternal, right?

Even if they are no longer here, there are things about them that live on forever in memories and stories that will be passed down from one person to another. I remember when a child was born in the hospital in Mariupol, I saw tears in their mother’s eyes. Even in such, let’s say, chaos, when it seems like only death awaits, new life can emerge. A sprout growing amid ruins gives hope that the world can still exist and there will be another tomorrow. War is indeed a part of life, an unfortunate reality, but it cannot extinguish life itself.

These are intense and impactful experiences that could deeply affect someone. Many individuals might shut down emotionally, become less sensitive, and avoid facing these emotions to prevent being overwhelmed again.

For instance, we previously discussed how professionals like resuscitators and rescuers who often deal with death can develop a sense of detachment. Have you ever felt a need to protect yourself by creating a barrier, distancing yourself a bit to avoid getting completely immersed in these situations?

Probably not. I realized that I have fully accepted this reality. Unfortunately, I cannot stop the war. It’s beyond my power. But I can be there and do something to support people, to tell their stories to the world. I’m not avoiding this reality; I face it head-on. Sometimes, I stare death in the face. Other times, I witness tragedies through human eyes. But I’m not afraid.

It sounds like a big choice.

Indeed it is. I think I made a conscious choice not to distance myself from it. I’ve always wanted to challenge notions of human selfishness or that people don’t care (about such things). I, for one, do care. And I think, overall, I’ve always been that way. But with war, I’ve become more resilient. And this choice has become solid as a rock. I can’t do it any other way. And I don’t want to. It saddens me greatly when people say, “I don’t want to see this.” You can’t hide from it! It has already happened.

It seems to me that all the awards your team has received don’t even reflect a tenth of the contribution you’ve made to world history. And they don’t reflect the uniqueness you possess: the combination of clarity in your professional actions to achieve your mission, while also having clarity in your humanistic choice. Professionals rarely take such clear and decisive steps while also being so unequivocal about their stance. Am I idealizing you a bit? Did those 20 days in Mariupol look like that?

They looked like that because we had made a specific decision to stay despite having a team ready to leave. It happened when we realized there were no more journalists in the city. There used to be many vans for the international press parked near the hotel where all the journalists stayed. One day, we arrived and realized only our van was left.

We made a clear decision to stay close to the people since there were many in the city. All our subsequent decisions stemmed from this. We simply didn’t have other options or any other agreements. Of course, it was difficult, especially when the shelling was very close or even right in front of us and when there was no hope of leaving. Still, something inside kept giving us the strength to get up in the morning and go to work, to just record interviews. There were times when we were stuck in the hospital and couldn’t leave. But we still kept doing something. There was no other option for our team.

This is felt in your film, photos, words, and actions. I believe all your heroes share this feeling. Another aspect that speaks volumes about you is how your heroes aren’t merely objects captured in the background of ruins by the camera lens or anonymous victims reduced to statistics. Despite the horrors and risks you faced, you captured their personalities and characters vividly. They are all very different. Could you share more about your relationships with these heroes?

Of course, we had relationships with most of the heroes, almost with everyone. Even if it was a very brief conversation, it leaves a mark on you for a lifetime. We approached the person, Mstyslav took the shots, and I asked questions. Afterward, we selected together what to include from the footage. We developed friendly, even familial bonds with some of the heroes. In such intense circumstances, you grow very close in a short time. When the reality of imminent danger hits you, masks come off, and there's no need to pretend or hide anything. You’re just who you are. It was the same with the doctors in the hospital. They really became like family to us. And I think we became part of their hospital. Even when we left for another place, they worried about us a lot, asking, “Where are they? Where are the journalists?” They missed us.

I communicate with Volodymyr who drove us out of Mariupol and risked his own life almost every day now. So, we have very close relationships. And this is so valuable to me. Because it’s important to me what happens to the heroes next and how their lives unfold. I keep in touch with many of them through messages. Some I chat with occasionally, while others I talk to more regularly.

Many of them are happy about the success of the film. They’re happy because they know the world sees it and pays attention to their stories and them. They follow this, always asking how the screenings went, what people said, and how they reacted. This reaction and feedback from other people, from the international community, are important to them. These are interesting relationships...

Understanding these individuals and empathizing with their emotions is a challenging yet essential task for a journalist. You could have chosen a more superficial approach, but you've opted for a more difficult yet compassionate path. These people are not just subjects; they are also connected to you in some way. This connection creates a moment of closeness, unlike the typical professional distance often maintained in journalism. We all consider distance in our work: signing contracts, writing books, or conducting scientific research requires a certain level of detachment. However, when it comes to portraying a hero, whether a historical figure or a building, even an architectural object, becoming captivated breaks that neutrality.

What do you think about this neutrality? Because it feels like distance isn’t your thing.

We are very often present during rather intimate moments in a person’s life, sometimes even during the most tragic ones. It requires a great level of sensitivity. Not everyone wants someone to be present there. There are people, of course, who want it and even say they want to share this grief. When we engage with them, we step into their world and share that moment with them. Even during a simple interview, we’re entering into their personal space. There’s always some kind of energetic exchange. My main focus is always on the goal, which is to listen to and support the person. It’s not about fulfilling my own needs. Sometimes, I set aside my camera and simply give that person a hug. Occasionally, I must let go of some heroes because I can’t keep everything in my head, either.

I don't believe there’s any neutrality in this situation. As a journalist, you remain an observer and aren't part of their family or anything like that. Yet, whenever I'm working, I always feel like I’m part of that family. My goal is to grasp the emotions shared between them, the phrases, and words, and then convey this to others. I aim to immerse the viewer in the story so they can feel and truly understand it rather than seeing it as distant and unrelated. After all, all people experience the same emotions.

Everyone feels love, pain, happiness, and sorrow. Only through these feelings can all of this be somehow conveyed to someone thousands of kilometers away. And for this, you need to spend more time with the heroes and delve into their lives. There’s neutrality here in the sense that you still maintain some distance, not being a part of this family or a part of this person’s life. But they allow you to enter their space. And I allow them to enter mine.

It seems like some sort of partnership with the hero, almost like co-authorship, doesn’t it?

It’s like we share a feeling; it’s empathy. There’s a psychologist who provides professional help. Then there’s someone who supports you, listens to you, and wants to amplify your voice and share it with others.

Maybe then the principle of objectivity and neutrality should be replaced by the principle of absence of condemnation?

I don’t feel condemnation toward anyone at all. I will never do that. I just don’t have it in me. We don’t know what a person has been through and what happened to them. As a journalist, I have no right to condemn anyone, and this holds even more true as a human being. I simply don’t want to condemn anyone. It’s my wish.

Did you talk about whether to include the part in the movie where some people from Mariupol were scared and accusing you of being agents and lying? Can you explain how you chose to include that?

We aimed to capture things as they were. When people face dire circumstances like living through chaos, lacking food, having to look after suffering children, or dealing with death, they are going through the worst moment of their lives. Of course, some people reacted to it more calmly while others did so aggressively. There were many different people and their reactions were normal because we are all different. Our differences mean that we react differently to situations. We understood that.

We wanted to show in the film what it was like. People often understood each other, but there were times when they didn’t. Anger was common because everyone felt scared. However, some remained calm, offering help, kind words, support, or hugs. Others reacted differently, being aggressive, shouting, or accusing others.

We stood out because we were press. Some people sought hope upon seeing us, while others sought someone to blame. The fact that we somehow stood out for the latter, in their opinion, made us guilty. We just showed it as it was in the film. Every person’s reaction, whether negative or positive, is portrayed just as it happened, as we believe each reaction holds significance.

Our reality is that our country is currently at war and is expected to remain so for a long time. As a result, there will be numerous consequences of war, ranging from terrible and unpleasant to frightening and diverse. Journalists, writers, and cultural activists will need to confront these negative aspects of our lives. However, amid this negativity, some stories and narratives can emerge, some of which may even contain elements of beauty, drama, and emotion.

As one of the youngest journalists ever to receive the Pulitzer Prize, what advice do you have for young journalists? Ukrainian professionals have a global platform to speak and be heard, which brings visibility. However, how should one handle personal trauma and negativity? Avoiding it and focusing solely on success isn’t effective anymore.

The key is to listen to your heart, as it guides you toward the right decisions and direction in life. It’s crucial to pay attention to your inner voice and not ignore it, even though it can be challenging to hear amid the world’s noise. You might feel like you don’t know what to do. But trust that your heart will always steer you in the right direction.

Even if it feels like everyone is against you, remember that many others face similar challenges. Communicating more is crucial because it helps you reflect and realize you’re not alone. During wartime, dealing with tough issues is normal, but taking action and moving forward brings meaning to it all. Every small step leads to progress, even if others doubt or criticize your efforts. Stay focused and keep moving forward—it’s all part of the process.

If you’re finding things very tough, consider reaching out to a psychologist or therapist. It’s okay to avoid topics that feel too distressing, and you shouldn’t push yourself unnecessarily. Follow your heart—if you feel compelled to spend time with someone or highlight something, go ahead. But if not, that’s okay too. Pay attention to your own needs to discover what brings you satisfaction at work. Speaking of satisfaction, it's a tricky topic, but for me, it’s knowing that someone smiled after our chat, feeling a bit uplifted, and realizing that someone cares about them and their problems.

I recommend that experienced editors also listen to and support young people, giving them chances to share their ideas. I’m grateful for the opportunity I had, especially during tough times, to prove myself and to show what I could do. Even though I lacked experience initially, being given a chance to work made all the difference. I used to doubt if I was good enough for an international agency, but they trusted me with work, and it turned out well in the end.

We should pay attention to each other.

And did you follow your heart?

Of course, I always followed my heart. That’s the only way. It’s such an interesting time because we have heroes among us, not just in movies but right here in real life. I feel honored to share the stories of these heroes, including medics, police officers, firefighters, soldiers, volunteers, mothers, children, and everyone else. These are inspiring stories, and it’s a privilege to document and showcase them.

Are you a mediator between them and society?

Yes. We did receive the Pulitzer Prize for serving society. And I also think that I probably serve society. This is my job.

When I tell someone about you, I start by showing them your Instagram. We scroll through until we reach the point just before the war, where your first photo from Mariupol shows you wearing a helmet and a Press vest. Before that, there are professional model photos showcasing you in beautiful dresses, with makeup—often in a lavender field—that create a striking contrast. How do you feel about this difference, this division, now that two years have passed?

I still love the beauty in everything. I appreciate nice clothes, beautiful people, movies, and cities. It has always inspired me, and it continues to do so. Personally, as a woman, I enjoy looking good, wearing dresses, and having nice things. I also like participating in photo shoots because they capture this beauty I carry. There’s a commonly-held stereotype that woman can only be smart, beautiful, or something else, but not all at once. I believe a woman can be multifaceted.

Speaking of Instagram, it’s a topic I enjoy discussing because, for many people who didn’t know me before, it presents a very striking contrast. This contrast isn’t unique to me; it’s something we’ve all experienced. creating a clear distinction between the period before the start of the war and the time after.

Now, many things don’t seem as important to me anymore. I don’t see the deep meaning in things like dressing up nicely or worrying about my appearance, because what truly matters now is life itself. Everything else has lost its significance.

In Mariupol, nothing seemed to matter except life and the people around me. When we left, I stopped caring about what clothes to wear, realizing they were just material possessions. But later on, I remember, I became obsessed with wanting to buy lingerie and cosmetics.

Oh, I also constantly buy underwear. I was so afraid of getting stuck somewhere in the field without a change of clothes that now I have a whole collection of different underwear.

I was somewhat out of my mind at that time. I had a strong desire to focus on caring for my hair —to trim it, to style it. It helped me regain a sense of normalcy. Now I understand that even though I wear tactical clothing and spend time on the front line during the war, I can still wear nice underwear underneath. That realization is comforting. I’m still interested in how I look, how I feel, and what perfumes I use, but these things are not as crucial as they once seemed. What truly matters now are the people around me. Although, I must admit, people and their lives were always the most important thing to me, even before.

Based on what you’ve said, it seems that there isn’t a clear division because the values that existed before remain the same. And these things still serve as tools for psychological support. It doesn’t mean anything more than that. We can return to the topic of 1940s Vogue magazines with photos by Lee Miller alongside perfume ads. We don’t criticize what the perfumes symbolized, as life often mixes different elements, just like a magazine where everything harmoniously coexists. Maybe there’s some beauty in this blending too.

To some degree, yes. But I still think that everyday life is more about thinking about perfumes and clothes rather than death. War, though, teaches unique lessons you can’t learn elsewhere. At this moment, I’m likely more mature because I’ve witnessed the world’s worst and also its best moments. I’m grappling with this concept because it’s not simple, but that’s the reality of our world.

You know, by talking now, you're helping others once more, including me and those who'll read this later. As you mentioned, for Ukrainians, life is like that—we don't have the luxury to just think about perfume. This reality will endure. So, the question arises: how do we adjust and narrate this tale in our own manner, where perfumes meet sorrow without breaking us emotionally?

But still, we haven’t lost the most important thing. No matter how hard Russians try to break and destroy Ukrainians, we won’t lose what we have inside of us. That’s incredibly powerful. Despite the cruel nature of the attacks we endure that have no other intent but to destroy us, life perseveres and carries on.

So, is this our resistance?

It’s the incredible strength of Ukrainians, the Ukrainian people, and the thirst for freedom. We help each other so much, showing that even in difficult situations, we remain human and support each other.

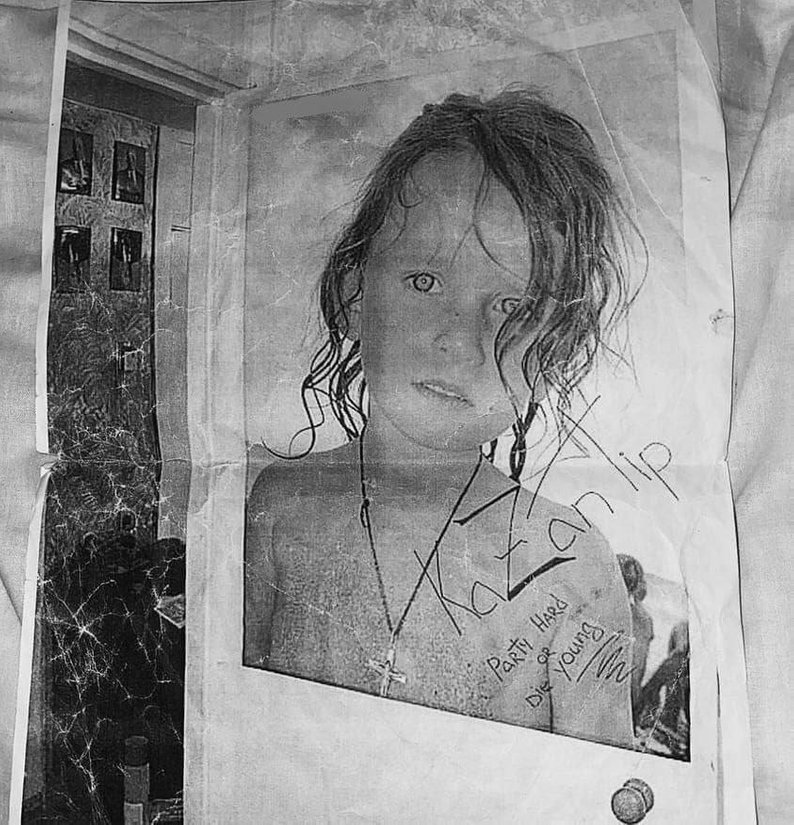

Before the full-scale war, I recall seeing a photo of you on Instagram from KaZantip [Editor’s note: an electronic dance music festival that took place every year from 1992 to 2013 on the Crimean Peninsula] when you were younger. Crimea is a very painful topic because, in so many respects, the war started there. We all grieve for Crimea. It’s not just about losing the land—Russia also attempted to take away our memories, our history, and our childhood dreams.

When I was 16 years old and spent a lot of time in Crimea, I remember how this photo became really popular. It was everywhere, on walls, T-shirts, and shared among people. It represented KaZantip and its idea of freedom and youth so well. Everyone, even kids, loved the vibe there. It was like a perfect community where children could be free and enjoy Crimea just like everyone else. This photo holds a special meaning for me. Can you tell me more about it? What exactly was it?

My mom, being a dancer, shared a lot with me about hip-hop and breakdance culture in Kharkiv; she played a foundational role in it there, you could say. Every summer, we would also attend different festivals together. There was a big breakdance festival in Yalta. And my mother was the only one who had a child because she was a bit older than the other people there. My mom always took me with her and never left me behind. Because of this, it felt like my mother and I had a special connection.

It turned out that I was always the only little child at all the gatherings, and it was a shock to some people. My grandmother told me that when I was 7 months old, they even took me to swim in the sea. People said, “You’re already taking such a small child to the sea?” And she replied, “If I threw you into the water, you would definitely swim.” I have a very active and creative family, and we are always together. They never left me alone anywhere.

Looking back on those experiences, they helped me feel at ease with certain aspects of field reporting, such as sleeping in unconventional places like basements. As a child I could sleep during the rave at KaZantip, right next to the stage where the music was playing. Mom said that some photographer took a photo of me on the beach, whose name she unfortunately doesn’t remember. The photo included an ironic caption: “Party hard, die young.”

We only had a copy of that photo. It was quite remarkable because I was likely the only young child at KaZantip. No one really considered bringing children there. But that’s how my childhood was—I often attended parties with my mother.

Well, you see, from childhood, if you're thrown into the sea, you'll swim.

My grandmother, who is an athlete, used to say that babies can swim naturally from the moment they are born. “You just have to throw them into the water,” according to her. It’s normal...

What will you say to all of us who are traumatized? Jump and swim?

Well, what else can we do? We can’t just stand still.

Well, not drown, that’s for sure.

We can’t let ourselves drown, no. We only have one life to live, and we should make the most of it. Don’t be afraid to take action or make changes. I understand that many people are hesitant to do certain things. However, we shouldn’t let fear hold us back; we should give it a try.

Let's jump.

Text originally published (in Ukrainian) by Suspilne Kultura as part of a collaboration with Documenting Ukraine.

Translated by Kate Tsurkan