The opening panel discussion of the symposium was titled Cool Head, Warm Heart: The Language of Emotions and Knowledge Production and focused on the epistemological value of emotions in documenting the Russo-Ukrainian war, as well as how one’s positionality affects the documentation and knowledge production processes. Ukrainian journalist Mariana Matveichuk shared how various emotions shaped her cooperation with foreign colleagues. She had to learn the importance of saying no to requests that might deem inappropriate or simply unethical in the long run, as the border between professional journalism and hunting for clickbait stories is rather thin. Anna Wylegała, a sociologist at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, reflected on her positionality as a Pole working in a Polish institution on a project about Ukrainians affected by war. She also shared the consequences of working on such difficult topics as a non-Ukrainian – without the commonality of experience, internationals must do more emotional labor.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

Journalist Terrell Jermaine Starr spoke about his experience reporting on Ukraine for an American audience—Black American in particular—and how he challenges his fellow Americans to stay morally consistent on various issues in times when everyone competes for their empathy. He also argued that people should strive for a better understanding of colonialism outside of their own context, and that in order to speak about decolonization one must cleanse one’s mind from one’s own ignorance. Olesya Khromeychuk, writer and director of Ukrainian Institute London, described her institution as a mediator of urgent knowledge about the war to the audiences who might not yet know they need this information. She also talked about stories of Ukrainians as human documents of the war, and how institutional and professional frameworks can limit their emotional expression.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

The next panel, How Far Can You Go: Everyday Geographies in Documentation, discussed the role of borders and physical bodies in documentation. Ioulia Shukan, lecturer in Slavic studies at the University Paris Nanterre, spoke about new inequalities for researchers that came to be because of the full-scale war. She argued that previous embodied knowledge of the field and social networks became advantages for established international scholars in the field of Ukrainian studies, whereas young scholars are currently forced to work on Ukraine from a distance because of institutional barriers limiting travel to the country. Independent sociologist Daryna Pyrogova stated that even though Ukrainian researchers are currently free to do fieldwork almost anywhere in Ukraine, they still have to follow internal regulations and safety protocols. She also shared the advantages of remote work, as she finds it to be more sincere and open than face-to-face contacts.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

Grzegorz Demel, anthropologist and sociologist at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences, focused on opportunities to build trust through geography, as knowledge of specific geographical contexts helps to develop familiarity and trust with the respondents. He revealed that it is not only people who move through space, but also discourses and perceptions. Andrii Usach, head of NGO After Silence, shared his experience of communication with local authorities during the war, as well as expansion of international collaboration frameworks. He is concerned, however, that many Western institutions still refer to Ukrainians as mere executors, and not equals in the knowledge production process.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

The panel Beyond Resourcification: Flows of Data, Finances and Knowledge brought together international experts working on Ukraine to discuss how institutions and individuals stimulate documentation work on and in Ukraine. The discussion was informed by the work of Asia Bazdyrieva and Victoria Donovan, among others, who have written about the “resourcification” of Ukraine. Participants of the panel contemplated how to maximize resource flows within an often hostile and conventional system and what is ethical to do in times of crisis. Sophie Lambroschini, researcher at the Centre Marc Bloch, explained how specific knowledge about the Ukrainian experience of the war can be applied to research other conflicts. Mischa Gabowitsch, historian at RECET, University of Vienna, focused on how personal relations drive the documentation work in Ukraine, as well as how to use the resources of the West to benefit the people from underrepresented countries who oftentimes lack institutional knowledge to further their research. Edward Serotta, founding director of Centropa, discussed not only his contribution to documentation of Ukrainian experiences, but also what knowledge he personally receives as a result of this work.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

Servers and Clouds in 50 Years: Documentation Technologies Today and the Sustainability of Archives in the Future discussed the usage of technology to make the archives that emerge from this war accessible and sustainable in the long run. Valentyna Humenna, archivist of the Ukraine War Archive, explained how the archive processes digital materials in forms of photos and videos submitted by eyewitnesses and open-source data. She also warned against AI-generated data. Andreas Fickers, director of the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History, explained how historical knowledge and imagination is affected by the development of documentation technologies. He then proceeded to elaborate on how historians can benefit from collaboration with archivists to produce historical knowledge in real time. Kyrylo Vylsobokov, director of the Archival Information Systems company, discussed the role digital technology plays in countering Russia’s distortion of history and questioned the future of grassroot archival initiatives.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

In From De Iure to De Facto: Legal Dimension of War Documenting, discussants spoke about the legal framework of documentation and ethics of handling personal information, as well as war crimes documentation in general. Dalila Mujagic, a legal expert researching usage of emerging technologies and visual documentation for accountability, delved into the question of how to elevate Russian war crimes in Ukraine to the level of international law, as well as how to navigate visual evidence and open-source data. Lawyer and member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union Olena Kuvaieva explained which mechanisms NGOs can use to bring justice to victims of Russian war crimes. Yuliia Habruk, a specialist in intellectual property law, clarified how to account for copyright in digital war documentation.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

Origins and Destinations: Decision-Making and the Possibility of Solidarity focused on decision-making in international cooperations as a driver of solidarity and sustainability. Felix Ackermann, historian and anthropologist at the University of Hagen, addressed the need to re-think the relationship between Western institutions and Ukraine, as well as overcome the “emergency mode” that has driven many Ukraine-centric initiatives in the past two and a half years. Journalist and co-founder of the Public Interest Journalism Lab Angelina Kariakina reflected on the very beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the multitudes of decisions that had to be made simultaneously. Volodymyr Sheiko, director general of the Ukrainian Institute, underscored the importance of Ukrainians assuming the right to speak on international platforms.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

Apart from workshops on the usage of visual documentation, ethics of data sharing, and challenges of interviewing, the final day of the symposium included a presentation of a new book series initiated by the Center for Urban History and INDEX: Institute for Documentation and Exchange: Stories of War: A Series on Documenting and Archiving. The series’s first volume Conversation with Those Who Ask About War, edited by Natalia Otrishchenko, is a collection of interviews with members of documentation initiatives, a story of conversations that happen during and after the symposium, as well as a therapeutic practice, which allows the people involved not only to see the value of their work from a different point of view, but also to break free from the flight-or-fight response of the initial phase of the war and return to one’s previous academic interests.

© Center for Urban History/Bohdan Yemets

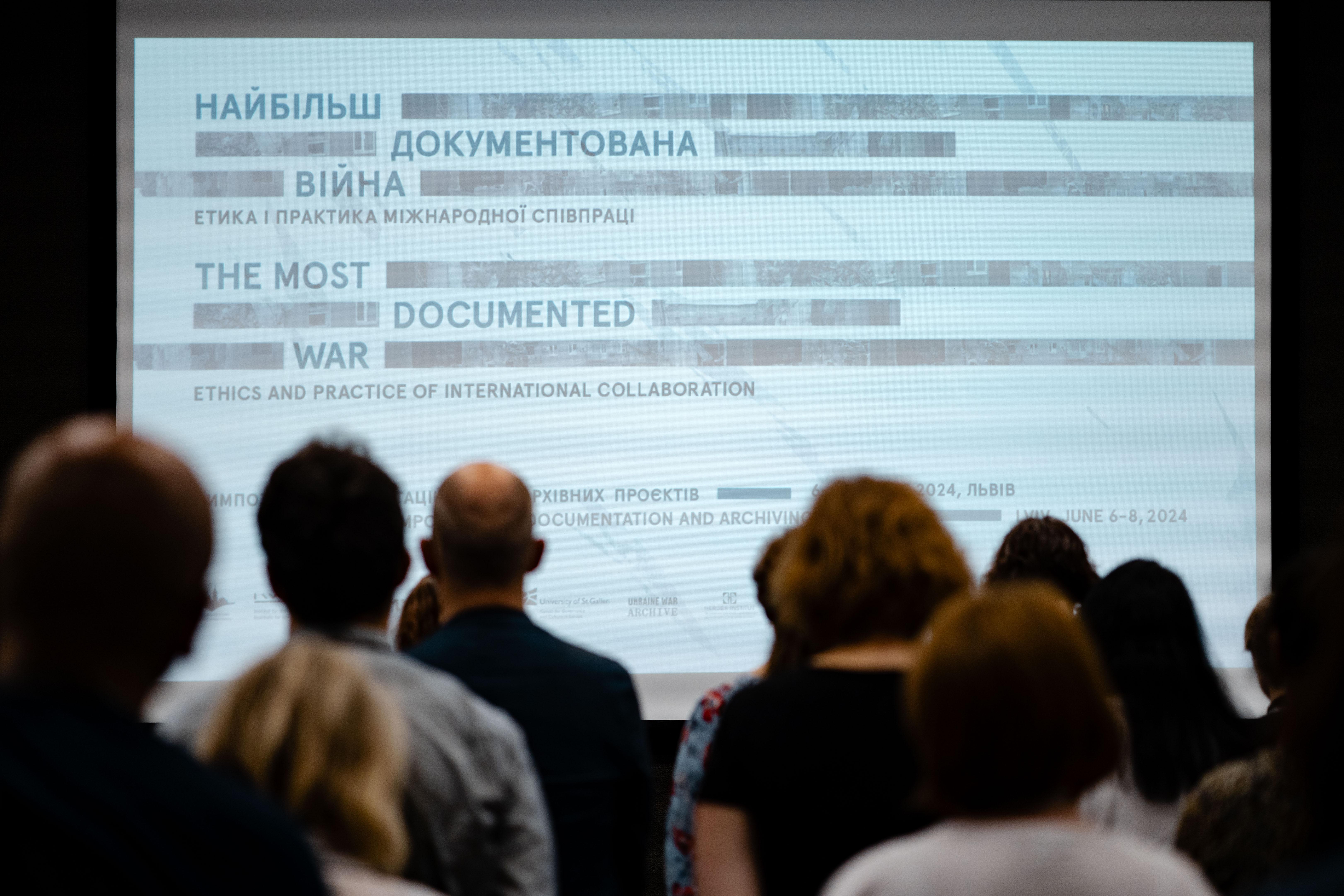

Another takeaway from The Most Documented War symposium is the creation of a catalogue of documenting initiatives under the same name, which accepts submission under the following link.