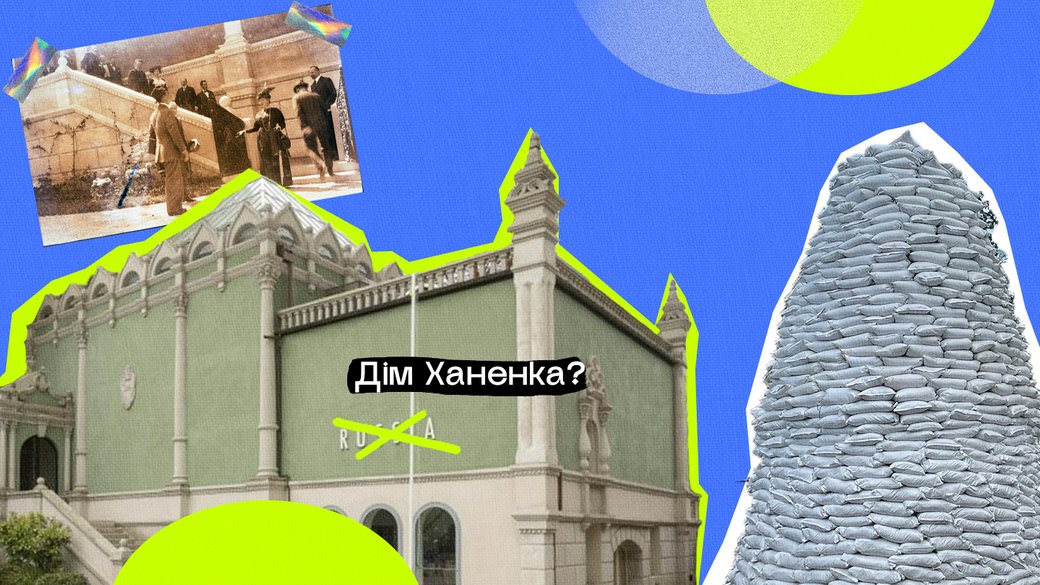

In the Giardini della Biennale in Venice, home to the biennial international art exhibition, a two-story squash-colored building sits on a hillside. Its facade overlooks the park’s central avenue and the rear windows and terrace overlook the park along the lagoon. It is one of 29 national pavilions in the Gardens of the Biennale, and was opened in 1914 according to a design by the architect Oleksiy Shchusev with the patronage and support of Bohdan Khanenko, a politician and entrepreneur from Ukraine during the times of empire.

It was already at the time of its second participation in the international exhibition that the pavilion changed hands from the Russian Empire to the newly minted Soviet Union. It was subsequently closed during the years of Stalin’s terror and World War II; it changed, aged, and needed renovation even before the collapse of the USSR. It was not until recently that the renovation was carried out in preparation for the Biennale of Architecture 2021 exhibition, united by the thematic question “How Will We Live Together?”

The Russian-Japanese architectural bureau KASA realized the project with funds from the Novatek gas company, owned by the Russian businessman Leonid Mikhelson, based on the results of the Open! competition. A year before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia used the pavilion in its hybrid war at an international cultural event, ostensibly demonstrating its openness to the world and engaging with representatives from different countries in a common cause. In the description of the renovation project, we read that "the venue for renewed institution of the Russian Federation Pavilion draws on “care” and “inclusivity” as a model in order to establish more empathetic and meaningful connections between architectural and digital environments, people and ecosystems.” For many years, the word ‘Russia’ has been clearly visible on the pavilion.

A year after the renovation, the pavilion was closed for the first time since 1934. A new phase of Russia's war against Ukraine had begun. The invited curator from Lithuania, Raimundas Malašauskas, announced the termination of the participation of the Russian project in the 59th Venice Biennale 2022, and security guards were deployed to the now-closed building.

In front of the pavilion, artists affiliated with Russia distanced themselves from war crimes; some Ukrainian men and women protested with a gesture of the middle finger raised towards the building; actions against military aggression were held; some graffiti appeared adding “Belo” to the “Russia” (1), etc. In 2023, the pavilion was also closed for the 18th Architecture Biennale, although the lights could occasionally be seen through the upper floor windows. The glass doors and walls looked like they had been spat on. And a month ago, at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024, the pavilion was reopened for the project of the Plurinational State of Bolivia: “Looking to the futurepast, we are treading forward.”

In Ukraine, the active rethinking of the Giardini pavilion began in 2022 during the first months of the high-intensity war. Bohdan Khanenko’s name was mentioned more frequently and shaped the conversation about the future of the building as well as its belonging to the Ukrainian context. As an independent state, Ukraine has officially participated in the Venice Biennale since 2001. However, even if the international exhibition has the status of one of the most important events of this type and is the oldest biennale in the world, in Ukraine, even those in professional circles have only the vaguest notion of it.

There are many reasons for this, one being that the books by art historian Oleg-Sydor Gibelinda Ukrainians at the Venice Biennale: One Hundred Years of Presence and La Biennale di Venezia. Motors of Art are bibliographic rarities. Other reasons include the difficult access to the event, which is expensive and isolated; the lack of permanent representation in the role of a Ukrainian Biennale commissioner; the lack of professional journalism, which, if it does appear, often suffers from a lack of fact-checking; and the fact that art and culture are generally on the periphery of state interests, and cultural diplomacy remains one of the underdeveloped pillars in Ukraine’s establishment of international partnerships and security during the resistance to Russian aggression.

The 2022 debate about Ukraine’s place at the Venice Biennale continues, and the issue of the pavilion, founded in 1914, remains unresolved. What should we do with this building? Should we keep it closed, should we rethink it, redefine it, or remove it from the gardens altogether, making way for a new pavilion? How can Ukraine get a legitimate voice in discussing the future of this edifice? It can be said that the ideas currently lack substance, and need to be fleshed out with concrete justifications for their implementation.

Therefore, in this partly speculative text that is essentially a list of theses, my task is to name and outline some possible directions for the future of the pavilion.

1. Two years of Ukraine in the Giardini, 2022, 2023

The history of the Venice Biennale begins in 1895 in the Giardini and national pavilions have been opening on this territory since the beginning of the 20th century. Ukraine did not have its own pavilion here for obvious reasons––but Ukrainian artists were presented many times: in the pavilion, which is now called the Russian Pavilion; in the central pavilion of the main exhibition, which is organized by new guest curators each time; or in the pavilions of other countries. For example, the Ukrainian section of works in the USSR Pavilion was singled out in 1930 and 1934 as “Ucraina.” In 1924 and 1932, the works of artists were attributed to cities: “Karkif,” “Kief,” “Pokrovsk,” etc. In 1920, in addition to the 81 works in the Pavillion della Russia, there was a separate “Mostra individuale di Alexandre Archipenko” (personal exhibition of Oleksandr Arkhypenko).

The Venice Biennale is one of many ways to trace the Ukrainian presence in the dynamic history of art. Outside of the national Pavilion of Ukraine, which has been changing locations since 2001, artists such as Mykhailo Boychuk, Ivan Padalka, Vasyl Sedlyar, Anatol Petrytskyi, Kazymyr Malevych, Serhiy Bratkov, Tetiana Yablonska, etc., were shown in the USSR Pavilion and the Russian Pavilion (i.e., in the same building); while Oleksandr Roitburd, Viktor Marushchenko, Mykola Ridny, Zhanna Kadyrova, Oleksandra Exter and Maria Prymachenko have featured in the main curatorial projects of different years. This year, the Open Group presents their work “Repeat after Me II” in the Polish Pavilion.

In 2022, the full-scale invasion caused a rapid revision of Ukraine’s place on the Venice Biennale map. On the one hand, there was a need to see the Ukrainian presence in previous exhibitions; on the other hand, it became a matter of urgency to present the works of artists who continued creating during the new phase of the war.

At the invitation of the curator of the 59th Venice Biennale Cecilia Alemani, an additional temporary Pavilion of Ukraine was created in the central part of the Giardini––Piazza Ucraina (Maidan Ukraine), a project supervised by Lizaveta German, Maria Lanko and myself in cooperation with architect Dana Kosmina, and with the participation of more than 70 authors whose works were exhibited in the format of a changing poster campaign. In 2023, the president of the Biennale, Roberto Cicutto, and its curator, Lesley Lokko, accepted the proposal from our curatorial team––consisting of myself, Iryna Miroshnykova and Oleksii Petrov––to work at this location for the second time.

This is how the Ukrainian Pavilion returned to the Biennale of Architecture after 9 years of absence, combining two locations––the space in the Arsenale and the lawn in the Giardini. About 40 Ukrainian architects as well as representatives from various fields such as art, history, archeology, ecology, etc. joined the project, entitled “Before the Future.” In 2022 and 2023, Ukraine received increased international attention as well as significant support from the Biennale as an institution.

Today, raising the issue of the Ukrainian Pavilion in the Giardini means engaging in a discussion on several levels at once, declaring one’s own positions while also getting into conversations that are already ongoing. We can characterize the current moment as a rethinking of the very model of pavilions through their deconstruction, through self-criticism or through exchange of spaces.

The imperial legacy of the built pavilions and the very principle of state representation is a theme that is critically elaborated both outside and inside the Biennale. (For example, Cecilia Alemani’s exhibition “The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History” in 2020, was an important phase, and in the pavilions of Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia, the projects of a Roma artist, an artist from Peru, an Estonian project, Sámi artists, artists from Greenland, etc. were on display.) Talking about the need for––and even more so about the construction of––a new pavilion means building a strategy contrary to these lines of thought. Therefore, any construction will require a lot of work, both diplomatic and scholarly.

2. Inconveniences of the Ukrainian Pavilion in the Arsenale, 2019–today

Today, the national Pavilion of Ukraine in Venice can hardly be called an institution. Rather, it is a place or a phenomenon in development created by temporary communities that, based on the results of the competition, by appointment or by invitation, take responsibility for its implementation. The continuity of this phenomenon is ensured by curators and teams, sometimes agents of state institutions––but never the institution that is nominally responsible for it.

In Ukraine, there are two such institutions: the Ministry of Culture for the art biennale and the Ministry of Infrastructure for the architectural one. The role of commissioner is either missing or unstable in these institutions. One curatorial team can outlive several commissioners within one year of work. Due to this instability, the knowledge and skills gained from previous projects remain unknown to future curators and commissioners.

Envisioning the Ukrainian Pavilion, which aspires to a long-term presence and visibility at the Biennale and possibly to receiving awards at this event, requires a more professionalized role of commissioners in the system of cultural policy. Anyone in this role should be familiar with the context of the Biennale and the nuances of participation in certain years. They should stay in constant contact with the Biennale team, with other pavilions, and with agents of the art/architecture field in Ukraine. Furthermore, they should support and promote whoever wins the competition to present their work at the national pavilion.

In 2019, the Commissioner of the Pavilion of Ukraine, Svitlana Fomenko, announced the intention of the Ministry of Culture to lease space in the Arsenale for 10 years. Previously, Ukraine had constantly been searching for suitable premises for its projects in Venice without success. This usually meant less visibility and difficult access to the project for visitors. Therefore, a fixed place in the Arsenale became an essential step for the national presentation. However, after four projects that were presented on the second floor of the Sale d'Armi of the Arsenale between 2022 and 2024, the discussion about the need to find a better place has been intensifying each time.

The problem is that the area of the Ukraine Pavilion is something of a pass-through space; rather than commanding attention, it is little more than a crossroads that leads to other pavilions or to the building exits. Six aisles and large windows make it difficult for teams to work. In 2021, the architecture studio “FORMA” calculated the limitations in using this space and found that the functional area was only 44%, while 56% of it could not be occupied in accordance with technical requirements.

The crossroads is generally a good metaphor. The Ukrainian projects take these inconveniences into account and use them to their advantage. Nevertheless, there are more and more calls to leave this space, both from the agents of the cultural field and the wider Ukrainian audience that sometimes loses focus and attention to the project due to the location’s cramped dimensions. This leads to several options for future development: to invest more in the national presence and enable work on projects of a larger scale (for example, in the Arsenale) or to return to the format of the nomadic pavilion (which will lead to a greater workload for the already overworked team).

3. The Khanenko Argument

There is also a third scenario: sanctions and/or reparations. The experience of war has led to the following considerations: Russia must give up or be deprived of the Giardini pavilion in favor of Ukraine, either after defeat on the battlefield or as part of new sanctions packages that may be imposed on the aggressor state. Although there is no direct correlation, the name of Bohdan Khanenko and a reminder of his role in the construction of the pavilion are likely to come up as part of these considerations.

One does not easily come across the name of Khanenko in Venice. Marco Mulazzani's popular book Guide to the Pavilions of the Venice Biennale of 1887, sold in all local bookstores, does not mention him. In the archives on the mainland of Venice, Bohdan Khanenko is listed in the official catalog of the Biennale of 1914 as one of the patrons of the pavilion and as the initiator of the Russian Empire’s participation in the Venice International Exhibition because of his direct connections with the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. In the British press of that time, one can find a mention of Khanenko as a “generous connoisseur of art.”

This reference to Khanenko leads to a number of questions: Can the patron of the architectural project, an elected member of the State Council of the Russian Empire from 1906 to 1912, qualify as a supporting figure in resolving the current issue of the Ukrainian Pavilion in Venice? What is more important: the fact that Khanenko supported cultural projects as a patron, or the fact that he participated in the creation of the Pavilion as ideological instigator ? The historic documents that could strengthen one or another line of argumentation remain difficult to access for Ukrainian scientists.

Researcher Mariana Varchuk points out that there are no such documents in Ukraine; the archival documents on the construction of the Russian Pavilion are kept in the Russian State Historical Archive in St. Petersburg. International researchers don’t mention Khanenko, apparently because they rely on the available Russian historiography.

In my opinion, the discussion around Khanenko is becoming stronger not only thanks to modern history but also to the activities at the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv, particularly during the full-scale invasion. The connection that exists between the construction of the pavilion in Venice and the museum located on Tereshchenkivska Street in Kyiv creates space for a gradual and thorough rethinking of the historical perspective on Khanenko. Thus, Khanenko can be seen at the center of a Ukrainian version of history and, from a decolonialization perspective, as a politician and industrialist of the 19th century.

Such conclusions may not be simple but scholarly work is the key to strong argumentation. It is not only the figure in the past that matters but also the formulation of today’s perspective, shaped in conversation and cooperation with many agents of the cultural field: Between 2022 and 2024, the Khanenko Museum hosted the exhibition “Fountain of Exhaustion” by Pavlo Makov (Pavilion of Ukraine 2022), the exhibition and discussion program “Before the Future” (Pavilion of Ukraine 2023) and the press conference “Net Making” (Pavilion of Ukraine 2024).

With a view to the past, further points of discussion arise: Why should the Pavilion, which is now called Russian and before that Soviet, and before that, Imperial, be ceded to Ukraine? Who else among international colleagues should participate in its discussion? Perhaps looking back to the initial scene of the pavilion’s construction and to the question of who created it does not provide the most reliable starting point.

4. The Case of Kabakov, 1993 and 2015

There is also a more recent historical connection in this conversation. Why does the pavilion in the Giardini belong to Russia now? Has it always been like this? A quick look at the projects after the collapse of the USSR shows that no, it has not. In 1993, it was not even called the Russian Pavilion but the Comunità Stati Indipendenti (the Commonwealth of Independent States) Pavilion. In Venice, several pavilions are shared, for example by the Czech Republic and the Scandinavian countries. In 1993, so was the house on the hill, which was not yet pumpkin-colored.

The exhibition at the 45th Venice Biennale was called “The Red Pavilion” and was designed by Ilja Kabakov, listed in the catalog as an artist from Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine, born in 1933 and living in New York. Thus, the independent states were represented by an international Ukrainian artist (with a complex biography).

Just as the name of Khanenko is not mentioned very often in Russian historiography, but instead is being erased and forgotten, so Ilya Kabakov’s participation underwent a gradual redefinition in the course of further activities of the Russian Pavilion. In 2015, the artist Iryna Nakhova presented her project “The Green Pavilion,” which reinterprets “The Red Pavilion” in the context of the historiography of Russian art and Moscow conceptualism and regarding the continuity between Russian artists of the 21st century and their predecessors. This continuity spans centuries and raises questions about humanity’s current challenges in a world of enduring political systems and a new ecological agenda. The 1993 Pavilion is consistently referred to as “Russian,” thereby ruling out the possibility of alternative interpretations. The colors of ecology mask the cultural-political methods of a deeply entrenched Putinism.

In 2017, Ilya Kabakov’s project won the national competition for the Pavilion of Ukraine. Having started working on the project, the artist contacted the curatorial group of Peter Doroshenko and Liliia Kudelia to inform them that he was unable to participate due to illness. At the same time, he was preparing for a major retrospective at London’s Tate Modern which opened during the Venice Biennale that year.

5. Bolivia and Ukraine

The story of how Bolivia received a pavilion in the Giardini in 2024 mirrors the story of how Ukraine lost the right to its own representation after 1993. In both cases, the strong connection between war and culture manifested itself in the exchange of resources for the possibility/impossibility of representation at the Venice Biennale. In June 2023, Bolivia signed an agreement for cooperation in lithium mining and production with the Russian State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom and in 2024, this cooperation was showcased at an international exhibition.

In her curatorial text, Esperanza Guevara (2) thanked the Russian Federation for welcoming Bolivia into the heart of the Bienniale. At the same time, the export of lithium batteries to Russia is subject to sanctions as they are used in the manufacture of weapons, including drones, which Russia uses on a daily basis against the Armed Forces of Ukraine and to carry out terrorist attacks on Ukrainian cities.

What happened between 1993 and1995, when the Commonwealth of Independent States Pavilion was given to Russia? The transfer process coincided with the development of the Russian gas war, during which, through 1994-1995, Ukraine received Russian gas in exchange for foreign assets and real estate from the Soviet Era.

Maxym Eristavi (3) proposes the following formula of Russian colonialism: “manipulation––invasion––extermination.” In the history of the Pavilion in the Giardini, it unfolds as follows: gas war––rewriting history (so that there are no awkward exceptions like 1993 or two interpretations regarding Kabakov’s connection to Russian art)––an invitation of Bolivia (under the direction of the Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalization of Bolivia)––...

Moreover, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov was in touch with Bolivia and supported the country’s entry into the BRICS economic union. At the same time, Lavrov’s daughter Ekaterina Vinokurova is one of the founders and owners of Smart Art––the company of the nominated commissioner of the Russian Pavilion from 2019 to 2029 (according to the current contract). We may recall the words of the director of the Hermitage Museum in Saint-Petersburg, Mikhail Piotrovsky, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion: “Before the start of the ‘special operation’ in Ukraine, exhibitions of Russian museums were everywhere. This was our, if you will, special operation, a big cultural offensive.”

In the recent history of the Russian Pavilion, the principle of indivisibility of war and cultural diplomacy is embodied by certain personalities. This year, as before, the aggressor country’s policy on international platforms continues to be determined by Vladimir Putin’s inner circle.

6. Prospects

At the 60th Venice Biennale, if you count the pavilions, the presence of Ukraine and Russia can be summed up with a relative score of 2:2.

The “Net Making” project by the curatorial team of Max Gorbatsky and Viktoria Bavykina, with the participation of artists Katya Buchatska, Oleksandr Burlaka, Lia Dostlieva, Andriy Dostliev, Andriy Rachynskyi and Daniil Revkovskyi; and the project “Repeat after Me II” by the Open Group with the curator Marta Czyż in Poland’s Pavilion were tactically balanced by the participation of Bolivia, which thanked Russia with lithium, and Austria’s Pavilion, which showcased Russian artist Anna Jermolaewa’s project about the fight against Putin’s regime through a ballet rehearsal (a separate issue).

Considering the dynamics of the last three years, it is clear that Ukraine remains visible and more independent at the international exhibition. Meanwhile, however, Russia has found an opportunity to rehearse its own comeback.

What the Venice Biennale of Architecture will be like in 2025 and the Art Biennale in 2026 largely depends on the work of many agents of the cultural and political fields within Ukraine. I am writing about this as an insider with an understanding of how much time and effort various issues require: Bohdan Khanenko and Varvara Khanenko, Ilya Kabakov and Emilia Kabakov, the history and criticism of the Pavilion, the construction of open permanent institutions, to name just a few. In order to have a set of short theses that can serve as the foundation for developing a strategy, it is necessary to conduct long-term and less dynamic studies. Such studies are confronted with many obstacles: time and financial resources; the prevailing lack of state recognition of agents of the cultural, artistic, and humanitarian fields; limited access to archives, etc.

Nevertheless, part of the work requires urgent action: the competition for the curators of the Ukrainian Pavilion at the 19th Biennale of Architecture has not yet been announced, and the very existence of the competition procedure remains uncertain. Can Ukraine allow itself to miss out on this event during the war? Can it afford to lose the results of all the previous years of work? In the timeline of the history of Ukrainian presence at the Venice Biennale, this is exactly where we are right now.

(1) The performance “TransSRSRversia” presented by the Belarusian actionist Oleksiy Kuzmich at the Venice Biennale in April 2022.

(2) Esperanza Guevara, the Minister of Cultures, Decolonization and Depatriarchalization

(3) Maxym Eristavi is a Ukrainian journalist, co-founder of Hromadske International

Text originally published (in Ukrainian) by Suspilne Kultura as part of a collaboration with Documenting Ukraine.

Translated by Dmytro Kyyan