Now We Know Who Wants Slovakia’s Fascists to Survive

A murder investigation has, by chance, cast disturbing light on an important court ruling that kept a fascist party in political business.

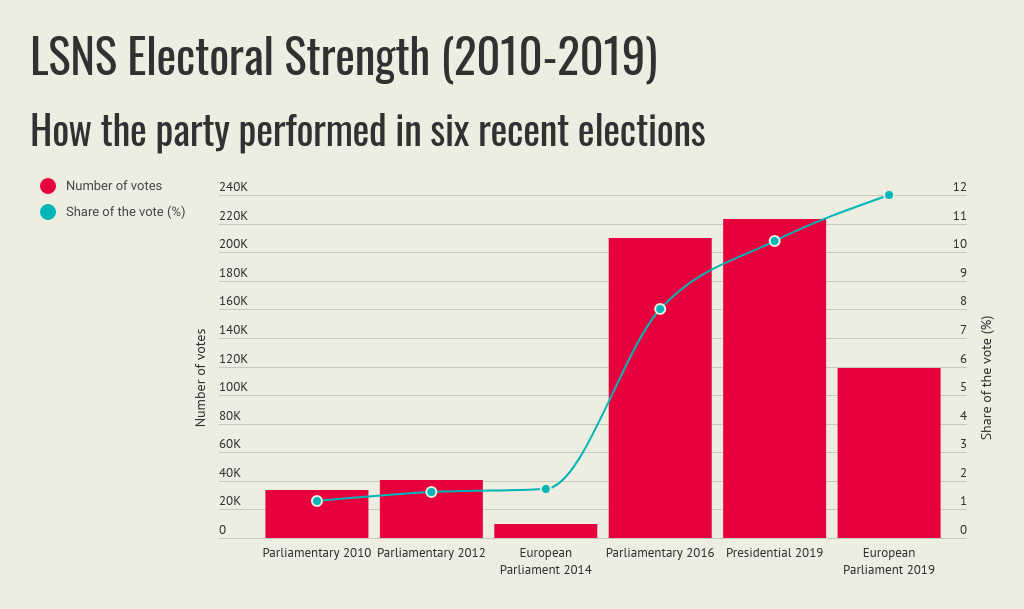

The decision was a long time coming — some two years since Slovakia’s Prosecutor General, Jaromir Ciznar, filed a motion with the Supreme Court to try to dissolve the far-right Our Party Our Slovakia (LSNS) on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. As the court mulled the case against the crypto-Nazi party, which had won 14 out of 150 seats in parliament in 2016 elections, the public was divided on the Prosecutor General’s move. On one side were those who argued that a court ruling to dissolve the party — even if such a ruling fully accorded with the law — could not eradicate a movement that clearly had popular support. According to this line of thinking, dissolving the party would not prevent another, similar party from emerging.

Moreover, it would only make political martyrs out of the outlawed extremists, who would then play on their alleged “suffering”. Extremists can only be defeated by a better, non-extremist policy, not by a court ruling, they argued. But those on the other side argued that if a democratic society creates mechanisms to protect itself, through the rule of law, those protections should override political questions such as: "What if banning a fascist party only increases popular support for fascists?" They argued that if society fails to act against extremists and just closes its eyes to their arrogance and expansion, this will only stimulate their activities and help them gain more votes. If the law is to be applied, and if the rule of law is to work, basic rules must be respected and enforced by a democratic state, they said; otherwise, the entire democratic structure could collapse. That debate raged from the moment the Prosecutor General filed the motion in May 2017. In the meantime, individual chapters of the file were made public through the media, and advocates of both streams of opinion began to assess the likelihood of the Supreme Court forcing the LSNS to shut up shop or continue as usual.

In estimating the chances of both scenarios, discussion revolved primarily around the quality of the complaint prepared by the Prosecutor General. Some lawyers pointed out that individual parts of the file did not appear convincing and missed out important facts. Others argued that facts about the party’s activities, regularly published in the media, are so obvious that the court would not have a problem in obtaining evidence to dissolve it. They also recalled that in 2006, the Supreme Court dissolved the Slovak Community – National Party, which had an almost identical profile and even the same leader, Marian Kotleba. So there was no reason why it should take a different decision in the case of the LSNS, they said. In the end, in April, the Supreme Court dismissed the Prosecutor General’s complaint and did not dissolve the party. The court justified its ruling by saying the complaint was insufficiently substantiated and did not contain enough evidence to warrant the party’s dissolution. The court did not take into account much verified evidence about the extremist activities of the LSNS and its representatives. But the court said it was not its duty to do so; rather, that was the duty of the Prosecutor General to present all the necessary facts.

The judges had dealt only with the 21-page complaint submitted by the Prosecutor General. A former Minister of Justice, Lucia Zitnanska, once characterized the motivation of such decisions as a "formalistic attempt by a judge to avoid responsibility for their decision." In this case, it was the five-member senate of the Supreme Court that tried to avoid taking political responsibility for its decision. Whatever the motives of the judges, the Supreme Court’s decision was timely — announced only weeks before elections for the European Parliament in May. The LSNS got plenty of political mileage out of the court’s decision, enthusiastically proclaiming to the public how it underlined the party’s “legitimacy” and “democratic character”. It also made much of the alleged efforts of its political opponents to persecute it without reason through the state authorities. Using the Supreme Court’s decision in its favor, it went on to become the third-strongest party in the EU elections in Slovakia.

Discussions about the Supreme Court’s decision then subsided. Recently, however, the issue floated to the surface again, in the unexpected — and almost unbelievable — context of a murder investigation. This happened after investigators into the 2018 murder of journalist Jan Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kusnirova, got into Threema app chats between the alleged mastermind of the crime, businessman Marian Kocner, and Alena Zsuzsova, his lover and apparent intermediary with the two suspected killers. Both Kocner and Zsuzsova have been in pre-trial custody since last year.

Among the huge numbers of text messages between the couple, filling up to 10,000 pages when printed out, was undeniable evidence of Kocner’s contacts with top officials, including former Prime Minister Robert Fico, former Interior Minister Robert Kalinak, former Prosecutor General Dobroslav Trnka, other prosecutors, high-level police officers, judges and so on. The Threema files revealed a lot of compromising information about how important state institutions operated — and how dangerously close mafia figures came to vital functions of the state. The chats have shown how, after Kuciak’s murder, Kocner anxiously followed political developments from the backstage and did his utmost to prevent the collapse of the Fico government, using his extensive personal contacts within the top political echelon. He was evidently afraid of losing his position in the establishment, and especially of losing the impunity he had enjoyed during those years.

Among the communications, for example, Kocner remarked that if one of the ruling coalition parties eventually left the government, under pressure from mass street protests, and if the government coalition then lost its majority in parliament, Kocner would strive for the government’s survival at all costs — using support from the LSNS. His most alarming phrase was that he had the leverage to force the LSNS to do so. "I arranged for the Supreme Court not to ban them," he wrote in one exchange with Zsuzsova. Two of the five judges of the Supreme Court senate who decided the fate of the LSNS promptly denied any link between their ruling and Kocner’s claims.

The public is likely to learn later whether things really happened in the way Kocner described them on Threema as other details of the investigation come to light. Besides the accusation of ordering the murder of Kuciak, Kocner faces tax fraud and forgery charges, so the investigation may take a while longer. The Kocner case has, however, revealed clearly who in Slovakia — apart from the fascists and their sympathizers — is interested in this extremist party remaining on the political scene. It is the joint interest of organized crime and a corrupt part of the political establishment. These are the ones who evidently rely on extremists in the last resort to retain both their power and their impunity.

The article gives the views of the author, not the position of the "Europe’s Futures–Ideas for Action" project or the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM).