Jan Patočka’s reflections on a post-European world remain an important resource for understanding the situation of contemporary humanity, which faces increasingly intractable problems on a global scale.

It is perhaps a truism that the larger questions of political life rarely yield conclusive answers. At most such questions are partially resolved, or settle into forms of varying urgency, tenacity, and relevance. Sometimes they renew themselves in strikingly different configurations, usually in response to the exigencies of a particular historical moment. This capacity for renewal is arguably characteristic of the political question of “Europe,” and one might propose tracing the history of Europe through the various permutations of its formulation, including during those long periods in which it failed to establish traction at all. Such an exercise would take us through some of the darkest but also most hopeful turns in this complex history. It would also naturally gravitate toward moments of transformation, when Europe seemed to be on the way from an old version of itself to something new, though without ever really breaking free from its past. In the wake of 1989, the prospect of a reunited Europe renewed but also reconfigured the question of Europe that had taken shape during its division post-1945, just as the revolutions of 1848 took up and transformed the idea of Europe that had emerged out of the French Revolution of 1789 and the Napoleonic Wars. The idea of Europe resurfaces again and again, or fades into the background, but it is never quite the same, nor does it ever prove to be a permanent acquisition. It is, to echo Jacques Derrida, always something à venir.

This protean character of the question of Europe is also evident when we survey the attempts at its philosophical formulation that, at least since the 18th century, have often accompanied the political discourse on things Europe. The recent publication of Europa und Nach-Europa, a selection of writings on the question of Europe by the Czech philosopher Jan Patočka, edited by Ludger Hagedorn and Klaus Nellen, arguably marks an important chapter in such a survey. Reflecting on Patočka’s reflections on Europe can perhaps orient how one might formulate the question today, philosophically and even politically.

Patočka’s discourse takes as its point of departure the recognition that the global preeminence of Europe has come to an end, an assessment that was still fresh in the postwar years in which he was writing. What is coming is not another Europe, but what comes after Europe. Politically, this involves, among other things, understanding the constellation of a global humanity no longer dominated by Europe, but still shaped by the myriad legacies of colonialism, technoscience, and capitalism that come after. Philosophically, the task is more ambiguous, for it inevitably leads to the question of the universal. Whether it takes the form of a simple identification, a promise, a hope, or an appeal, in some way or other the idea of the universal is almost without exception implicated in the idea of Europe.

There has always been something paradoxical about this implication of the universal in Europe. Universality, if it is to be more than an empty gesture, must be irreducible to particularity, including the contingent self-understanding of a group of peoples who live on a “petit cap du continent asiatique,” to borrow an apt expression from Paul Valéry. Thus the ambiguity of the implication: what is special about Europe is that it cannot be special. The ambiguity has consequences: it supports the pernicious identification of being human with being European and obfuscates the claims of universality by allowing them to get caught up in the nets of a European exceptionalism that would seek to bend the arc of the universal back into its continentality. It is difficult to avoid the feeling that decoupling the two would be better for both.

Something shifts, however, when the question is no longer about Europe but about what comes after Europe. For the claims of European universality have always distorted a truth that is of lasting importance: the awareness that thinking always takes place in a situation, even a thinking that strives for the universal. Particularity is not something we can avoid. The importance of the universal, in turn, is rooted in an awareness that the question of who we are cannot be formulated within the limits of a closed situation but must relate to what opens our situation onto the possible. This is a key theme in Patočka’s writings: what is at stake in the situation in which we find ourselves is the openness that human beings are, or how we are to engage our collective life as a life in possibilities.

There are several aspects of Patočka’s approach to the question of Europe and what comes after that merit emphasis. The first is his keen interest in how philosophy emerges and establishes itself in the world as a way of life, even a form of civilization. The Europe Patočka is interested in is the one that he takes to be animated by a spirit he associates with the Platonic motif of the “care for the soul.” The care for the soul can be understood as the concert of three spiritual attitudes that inaugurate a distinctive human posture: a drive to question that forms the impetus of philosophy, an embrace of risk that forms the core of political life, and a relation to an open, indeterminate future that characterizes a specifically historical consciousness. All these attitudes are for Patočka co-original, and they come together in the figure of responsibility. They pre-date Europe proper, intertwine throughout its history in a serious of complex configurations, and remain contested ground in the wake of its collapse.

Another salient feature of Patočka’s reflections is that this trifecta of philosophy, politics, and history is not assumed to be a fixed constellation. Patočka’s emphasis is instead on the contingencies that give unexpected urgency to our questions, throwing us back on our responsibility instead of conforming to any logic of events that we imagine to be at work in the world. The history of the care for the soul is thus composed of a series of renewals formulated in the wake of a sequence of failures: the collapse of the polis, the fall of Rome, the waning of the medieval world, the catastrophe of the wars of the 20th century. The question of post-Europe is, accordingly, whether the death of Europe in the 20th century brings this history to an end, closing off any question of the possibility of a new configuration of philosophy, politics, and history, or whether something like a global emergence of a universal civilization is possible, one that would no longer be European but distinctively human.

This question for Patočka is a real one, and not a mere rhetorical introduction to another rehearsal of the conception of a universal humanity. It is a real question because of the distinctive danger that Patočka sees in the marriage of technology and science that he takes to be characteristic of the contemporary world. Technoscience buries the last vestiges of the ancient commitment to insight in favor of the capacity to predict, inaugurating the ascetic nihilism of a purely instrumental rationality. Europe as techno-civilization has become a global instrumentarium for the pursuit and management of power for its own sake. There is at times a palpable sense in Patočka’s writings that, whatever the future may be for the care for the soul, it will draw from a vitality that comes from elsewhere than Europe, which has all but been reduced to a hollow colossus of power that no longer carries any genuine promise of meaning.

The last lines in the texts assembled in Europa und Nach-Europa were penned almost a half-century ago. Many of the philosophical and political questions Patočka asks remain alive but the global post-European civilization he hoped for shows no signs of becoming a reality. At most we might point to a heightened sense of a shared situation, but even that has limits, as the growing tragedy of the climate disaster is showing us. Maybe the very figure of civilization is misleading, since it directs our gaze away from the irreducible plurality of humanity. “There is no civilization as such,” Patočka writes in the Heretical Essays, “the question is whether historical humans are still willing to embrace history.” Perhaps this should be the opening premise of any reflection on Patočka’s reflections on what comes after Europe, and the place of philosophy within it: the urgent need to embrace our common future as a collective task.

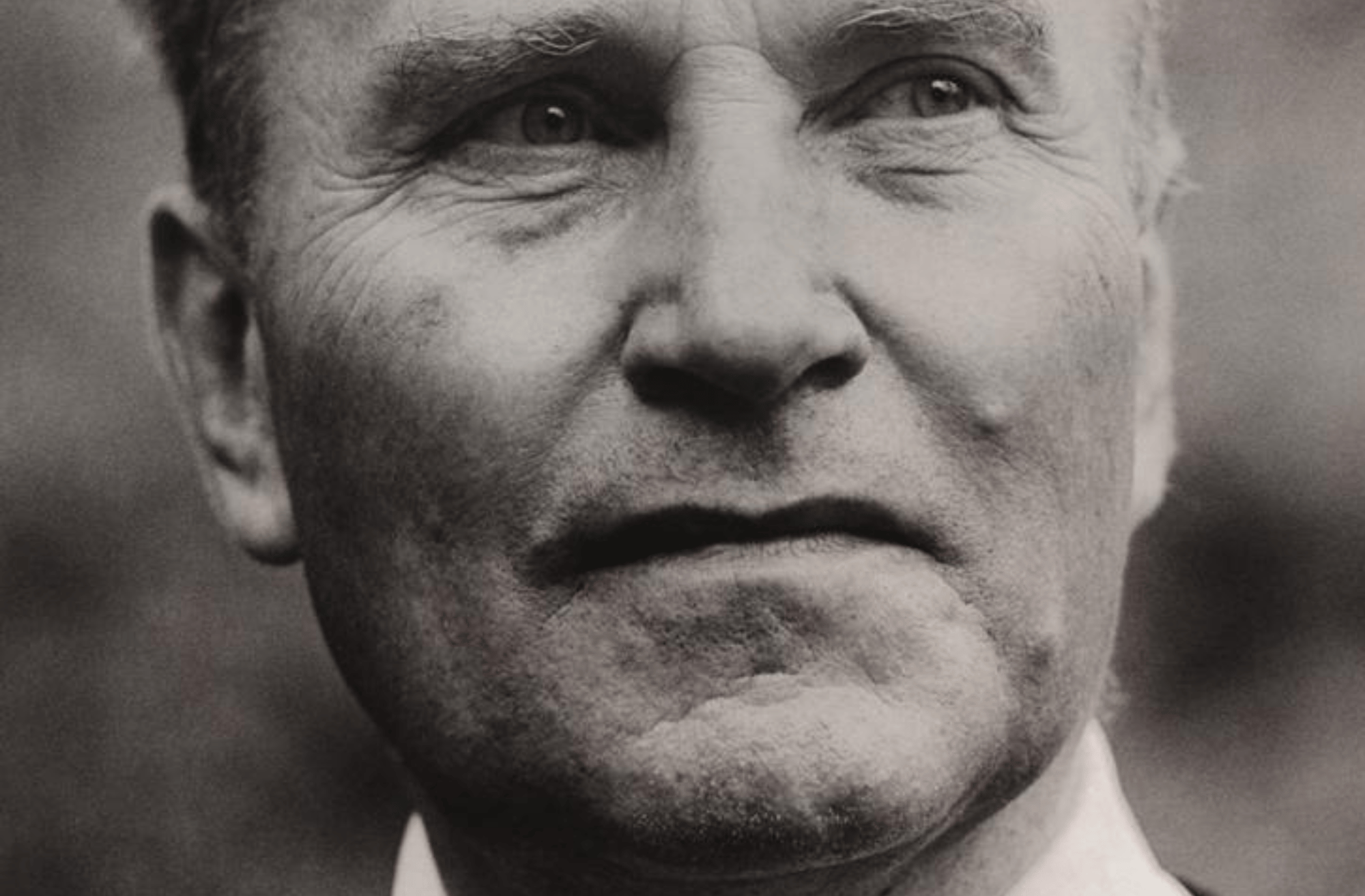

James Dodd is professor of philosophy at the New School of Social Research in New York and recurrent visiting fellow at the IWM.