The Socratic tradition inaugurated the care of the soul as the essential practice of philosophical reflection that is definitive for who we are and how we are. From Plato to Patočka, care of the soul is fundamental. This practice of reflection and open inquiry is still needed, especially in times of sedimented polarization. We should reflect upon how we might we promote the care for the soul in ourselves and others.

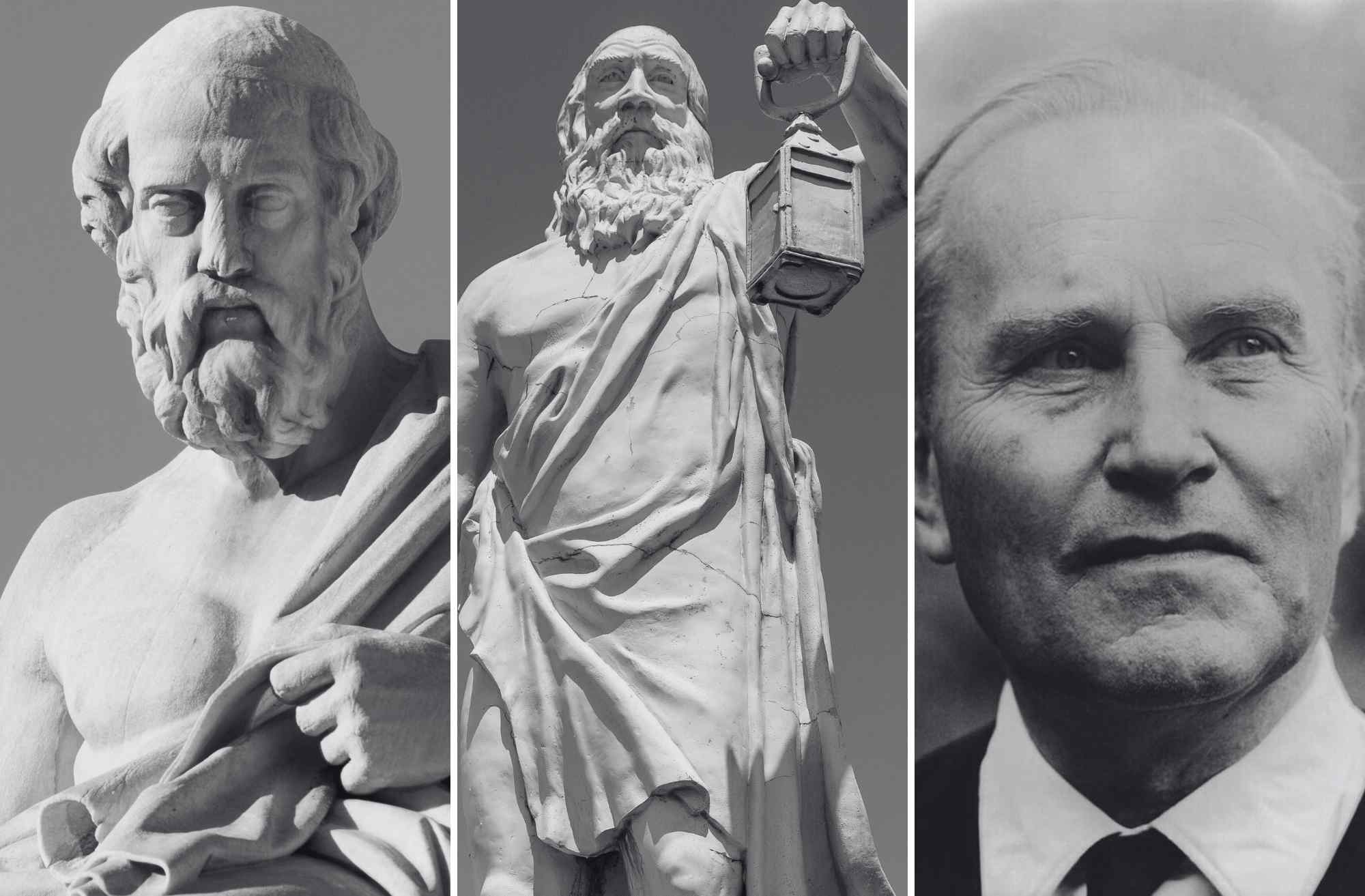

There is an old battle of wits, a contest between two luminary figures of philosophy. On the one side sits Plato, the great writer of Socratic dialogue, whose abstract ideas or “forms” are still a subject of examination and inspiration in countless philosophy seminars. Plato’s legacy runs wide, and in reading him we continue to ask important questions: Is an ideal social arrangement possible? Would there be more justice if rulers where philosophers?

On another side we find the cynic Diogenes who sits in his barrel, going outside to shine his lantern on the ways we tend to behave by acting shamelessly in public. While he makes fun of Plato, and almost everyone else, he can be understood not as a modern cynic but as a philosopher of care. His antics are intended to make visible the unreflective ways we act. Where Plato comes from an aristocratic family and discusses philosophy with eager students, Diogenes appears as a homeless beggar who, rather like Socrates, engages in public antics with the hoi polloi in the market, at festivals, and at other gatherings. They offer two different paths for seeking truth: one from above, one from below.

Plato and Diogenes reflect different approaches to the maxim “know thyself.” But to do that, to acquire something even approaching self-knowledge requires care. Care should not be understood as a response to illness or social stress, a bromide of yoga to undo the accumulated aches of daily life; rather care as epimeleia is more active than reactive—to care for the soul is to be what we are. To this end, in order to live well, to live in accord with ourself, Socrates, Plato, and even Diogenes suggest that we must cultivate our soul that animates our life, including our thoughts and beliefs. So how can we best care for our soul or cultivate the self?

Socrates was known as a gadfly in Athens. His irritating behavior was to ask if someone knew and could truly define ethical ideas like virtue or justice, showing those who would listen that those who claim to know about virtue do not. But this kind of display irritated politicians and defenders of power, leading to his execution. This Socratic practice also put on display a continued seeking after what is unknown, and this practice is the care for the soul; by engaging its activity to openly examine and reflect, the soul is both utilized and exercised. Insofar as Socrates challenged his audience to examine ethical ideas, he was acting not only in his own self-interest but also in the interest of others individually and collectively, shaking apart sedimented opinions. In this way gadfly-ism could or should promote a healthy reconsideration of our social commitments and beliefs while displaying the practice of the care for the soul.

Plato provides this account of Socrates, so it is no stretch to see that the philosophical maxim to “know thyself” and to care for the soul are part of the bedrock of Plato’s philosophy. While Socrates spoke in public and never wrote, Plato offers a different engagement in dramatic dialogue form. These dialogues persist and continue to provoke open discourse and, in doing so, promote the care for the soul, but they have a limited effect and an even more limited readership.

What about Diogenes? He is known less as a philosopher and more as a countercultural persona. Indeed, he is the one who speaks courageously against Alexander the Great, who lights his lantern during the day, and who challenged dogmatic religion, public decorum, and conventional living. How do his street antics, far from the discussions with Plato in his Academy, reflect a care for the self as a care for the soul?

Diogenes claimed that the public was uninterested in discussing serious matters of philosophy. Yet, he noticed that if he acted strangely, he would draw a crowd. People were more interested in looking at nonsense than speaking about matters of virtue! Following this insight, Diogenes took up the task of acting doggishly in an attempt to more directly confront contingent behaviors. He was “Socrates gone mad,” as one account says, and his confrontations are the prelude to open discourse in the form of care. He routinely caused embarrassment but, in doing so, tried to occasion the possibility of social change. He claimed to a youth who was blushing in embarrassment “Cheer up! Blushing is a hue of virtue!”

Diogenes acted in this way to confront civic behavior in order to occasion open thinking about alternatives. Alterity, if it can be taken without offense, alerts the public that social practices are contingent. The cynic tries to put the public into a position to reconsider who has power and who does not, what the value of money is, what should be private and public, and so forth. It is done through scandalous street antics because it attempts to draw a crowd to address social issues from below, outside the elite aspects of the Academy. It is a public call to care for the soul—to open a horizon of reflection on what social arrangements might be reconsidered. But is this kind of confrontation, perhaps satire today, apropos for the care of the soul? Or does it merely isolate those who feel shame and embarrassment? Perhaps this is why the cynic demands that we have strength.

Centuries later, a thinker who was far from a cynic but who was a figurehead for social change nonetheless, Jan Patočka, also asked us to reconsider the importance of the care for the soul. For him, care for the soul is the fundamental tradition of the West, a practice of openness and inquiry that allows one to live in truth. For Patočka, the history of Europe can be seen as the history of the care for the soul in decline. Overcome by materialism, dogmatism, ideology, and determinism, the care to seek and to know has steadily been overtaken by the care to have and the care to have determined. This story, the decline of Europe as the history of the care of the soul, is rich and complex, but what I want to consider is his notion of the rupturing that might alert us again, in solidarity, to the openness of the care of the soul as a society.

Patočka suggests at the end of the Heretical Essays that what offers such a possibility is not a return to Plato if that means thinking about ascending to the abstract realm of ideas, nor a social provocation like Diogenes, but a radical rupture in the form of a cataclysm that forces open a horizon by taking down the edifice of our social, political, and philosophical commitments that have become sclerotic in modern society. The rupture of having been shaken by the catastrophe of life on the front line of war is the example Patočka uses to illustrate the solidarity to reorient care as the essential openness in the soul.

But do we need a radical rupture to dislodge sedimented disregard for philosophical openness? Does Diogenes’s provocation or perhaps our modern equivalent in a character like Borat offer a helpful push from below? If so, how do we recognize Diogenes from a mere troll? Has the emancipatory hopes of Diogenes run afoul in the success of the more conservative forces of today? Perhaps Plato’s Academy is the way to promote the care of the soul best, but the time required to read and discuss and to place our beliefs in dialogue with Socrates and others seems to restrict the cultivation of care to those with leisure or privilege. In the Socratic spirit we might begin by asking why.

Darren M. Gardner is an adjunct assistant professor at New York University’s Liberal Studies department. He was a guest at the IWM in 2024.