Conversations with Dostoevsky on God, Russia, Literature, and Life (Oxford University Press, 2024), presents a series of fictional conversations between the Russian author and a Glasgow University academic, experiencing a midlife crisis. These cover issues from metaphysical despair, through Dostoevsky’s politics, to what, following Orthodox liturgy, Dostoevsky calls “eternal memory.”

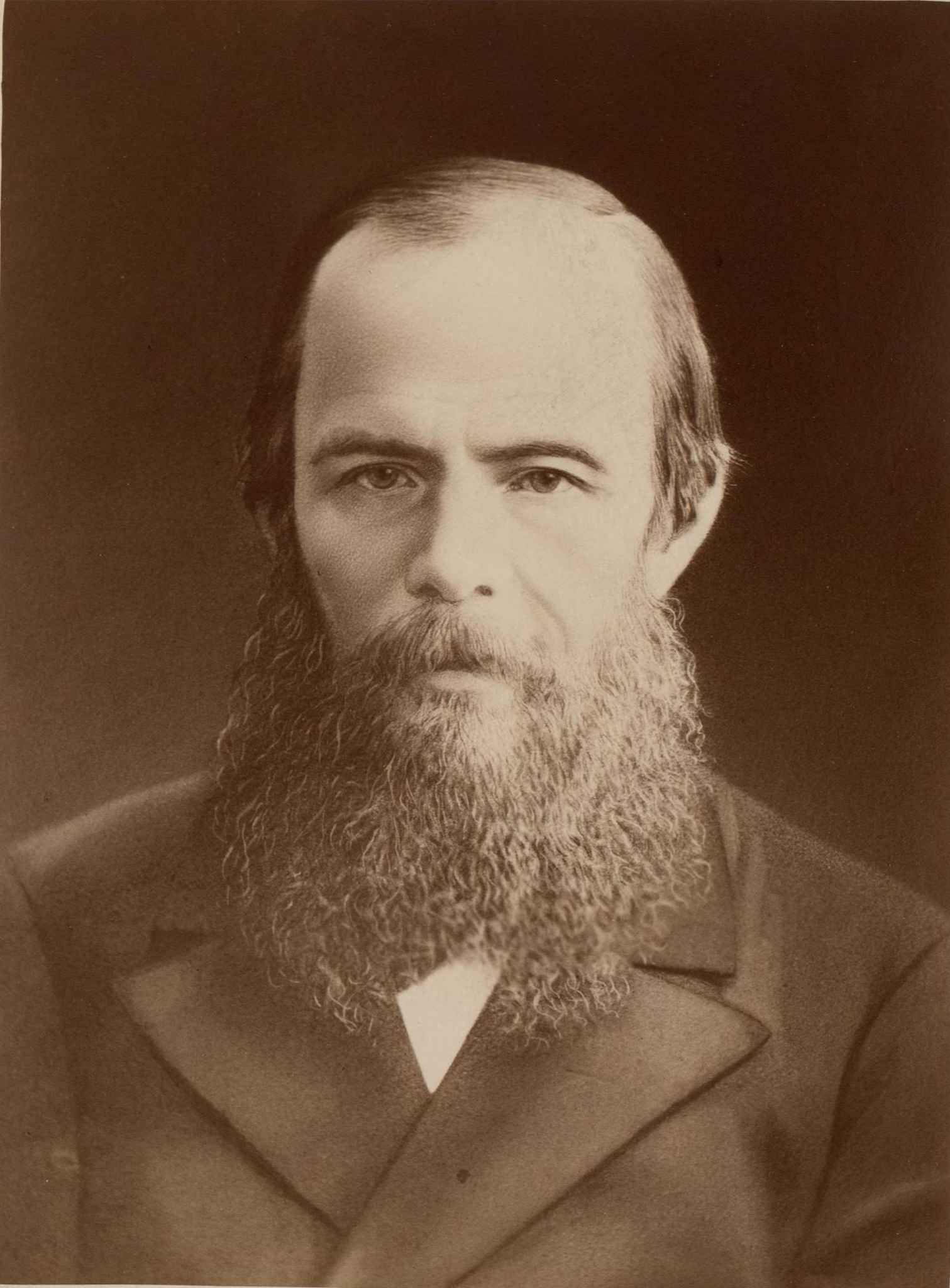

In the 150 years since his death, Fyodor Dostoevsky has been read in many different ways. In his lifetime, he was celebrated as speaking for the socially marginalized, the “poor folk” and the convicts among whom he had lived. To his first Western readers he revealed the depth and pathos of “the Russian soul” before becoming the prophet of the revolution. Friedrich Nietzsche said of him that he was the only writer from whom he had learned anything in psychology, while Albert Camus and other existentialists read him as giving voice to their own protest atheism. For some Christian readers Dostoevsky is an apologist for Russian Orthodoxy, but for others he represents a more humanistic kind of faith, not exclusive to any one church. His literary originality has provoked intense admiration and equally assured dismissal—Virginia Woolf once said he was clearly the greatest novelist who ever lived, but Vladimir Nabokov thought him “rather mediocre.” Today, he is cited by President Vladimir Putin in support of a fundamental clash of civilizations between Russia and the West, giving us a political Dostoevsky stripped of all nuance and ambiguity.

Each of these readings has some basis in Dostoevsky’s writings. Nevertheless, reflecting on the long, tortuous, and sometimes risible history of Dostoevsky reception, we soon realize that the issue is not only what he wrote or even how he wrote it, but how each generation is reading him in the light of its own questions and concerns. That is probably true of all literature, but it is—inevitably—all the more strikingly true in the case of a writer like Dostoevsky, whose work is so consistently extreme, intense, conflicted, and existentially demanding.

Since the end of the Soviet Union, international Dostoevsky research has been immeasurably enriched by the easy flow of scholarly exchange between Russia and the West, and Dostoevsky scholarship today is at a high point of academic achievement. How the new Iron Curtain will affect future developments is unknowable, though it should be mentioned that the International Dostoevsky Society places a strongly worded denunciation of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine at the top of its web page. Yet alongside scholarship—always necessary and always to be listened to—there is always the question as to the existential motivations that draw people to Dostoevsky’s work. For many, this remains his power to illuminate humanity’s religious or, as some would prefer, “spiritual” impulse—whether or not this is identified with Russian Orthodoxy.

However, whether we think of this as religious, spiritual, or Orthodox, what Dostoevsky says about God is intimately connected with his beliefs about Russia and Russia’s spiritual vocation to renew Orthodox Christianity. This is now inescapably problematic. His political journalism clearly articulates a kind of Russian exceptionalism, as in his conviction that Russia was divinely destined to seize Constantinople and restore it as the capital of Orthodox Christianity. His novels too contain passages that resonate with a strongly nationalist sensibility, although these always require careful reading, taking into account the character who is speaking, to whom they are speaking, and the specific context within the novel. The most discussed example is the speech by Ivan Shatov (in Demons) that Russia is a god-bearing nation. But while some have read this as a more or less straightforward expression of Dostoevsky’s own views, it is also very possible to read this as, in fact, a demonstration of how not to mix religion and politics. Indeed, there are strong indications in the novel that Shatov’s messianic nationalism is no less atheistic than the various other kinds of demonic possession unmasked there. Nevertheless, such questions cannot today be easily excised, not even if we give full weight to the philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s insight into the polyphonic nature of Dostoevsky’s novels and the way in which they present multiple voices engaged in ongoing and open-ended dialogue. True, Dostoevsky never or very rarely gives us a direct statement in his own voice, but his choice of topics and his delineation of character is already setting a certain agenda. In his influential 1923 study, the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev simply brushed aside what he saw as Dostoevsky’s religious populism and “messianic pretensions” as an “aberration,” but it is not so easy for us to do that today.

At the same time, Dostoevsky never saw “Russia” solely in political or even religious terms: for him, as a writer, it was inseparable from Russian literature and the question of its destiny was also a question of Russian literature’s place in what we could call the global economy of literature. Russia’s “new word” to the world was, in this perspective, not to be propagated by the sword but by its writers—and, as Dostoevsky himself acknowledged, even though Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol were decisive, he could only have become the writer he became in dialogue with Charles Dickens, George Sand, Victor Hugo, William Shakespeare, Miguel de Cervantes, and other figures of Western literature (two Dickens novels, for example, were the only books he was able to read in his four years in the penal colony, apart from the New Testament and some magazines). Of course, this does not immediately solve the question of Dostoevsky’s nationalism and its implications, since we are now sensitized to the role that literature has played in reinforcing national identities and national ambitions across the board and Dostoevsky, like so many Western authors of the 19th century, must undergo the scrutiny of a postcolonial reading. This is all the more so since literature was not just a matter for private readers or literary salons for Dostoevsky: literature mattered only to the extent that it engaged questions of life and helped readers to live their lives more fully, individually and in community. Dostoevsky did not, of course, know the expression littérature engagée but this was certainly what he practised.

If the generation of interwar émigrés could create a Dostoevsky who represented a universally human faith of humble, active love untrammelled by Russian exceptionalism, the post-Soviet legitimation of Dostoevsky has effectively closed this option. It may yet be that the defining curve of Dostoevsky’s thought takes it beyond the narrowly nationalistic (I think it does), but this is undoubtedly an obstacle that we now have to confront in a manner and to a degree that earlier generations did not. Of course, if Dostoevsky was only the anti-Western polemicist that Putin perhaps wants him to be, then it would be tempting to walk away. But no great writer can ever be fitted into the narrow gauge of any ideological project. Literature is more than propaganda, even when it is used for propagandistic purposes. Literature requires us to work at the truths with which it presents us, not merely to pass the message on to its designated recipients. Literature disturbs, disrupts, and demands attention to the text and self-examination on the part of the reader. Again, this is true of all great literature but eminently true in the case of Dostoevsky. He certainly does not emerge unscathed from this kind of reading and there are pages we must resist. Nevertheless, even when Dostoevsky is at what we might regard as his worst he has an uncanny knack of bringing decisive questions to a head and casting them in a light that shows subtle and contrary tendencies. To read Dostoevsky today, we must match a hermeneutics of suspicion with an openness to the text—and see where that goes.

This is why my book Conversations with Dostoevsky is just that: a series of fictional conversations, not studies, since conversations do not pretend to yield results or outcomes but can nevertheless deepen and extend the issues at play in them as well as allow for unresolved knots and perhaps unresolvable disagreements. None of this is easy—but nor is God, or Russia, or literature, or life.

George Pattison is honorary professional research fellow at the School of Critical Studies, University of Glasgow. He was a visiting fellow at the IWM in 2023.