Populism and technocracy are ordinarily understood as antithetical: each presents itself as a response to problems created or exacerbated by the other. Yet the digital revolution has paradoxically fostered both, leading to a new form of technopopulism.

Digital hyperconnectivity accentuates the chronic populism of late modern societies in two ways. First, it is a technology—and an ideology—of immediacy or disintermediation. Hyperconnectivity disrupts or circumvents institutional intermediaries of all kinds; it promises to connect people directly to news and information, audiences directly to creators, and citizens directly to political leaders.

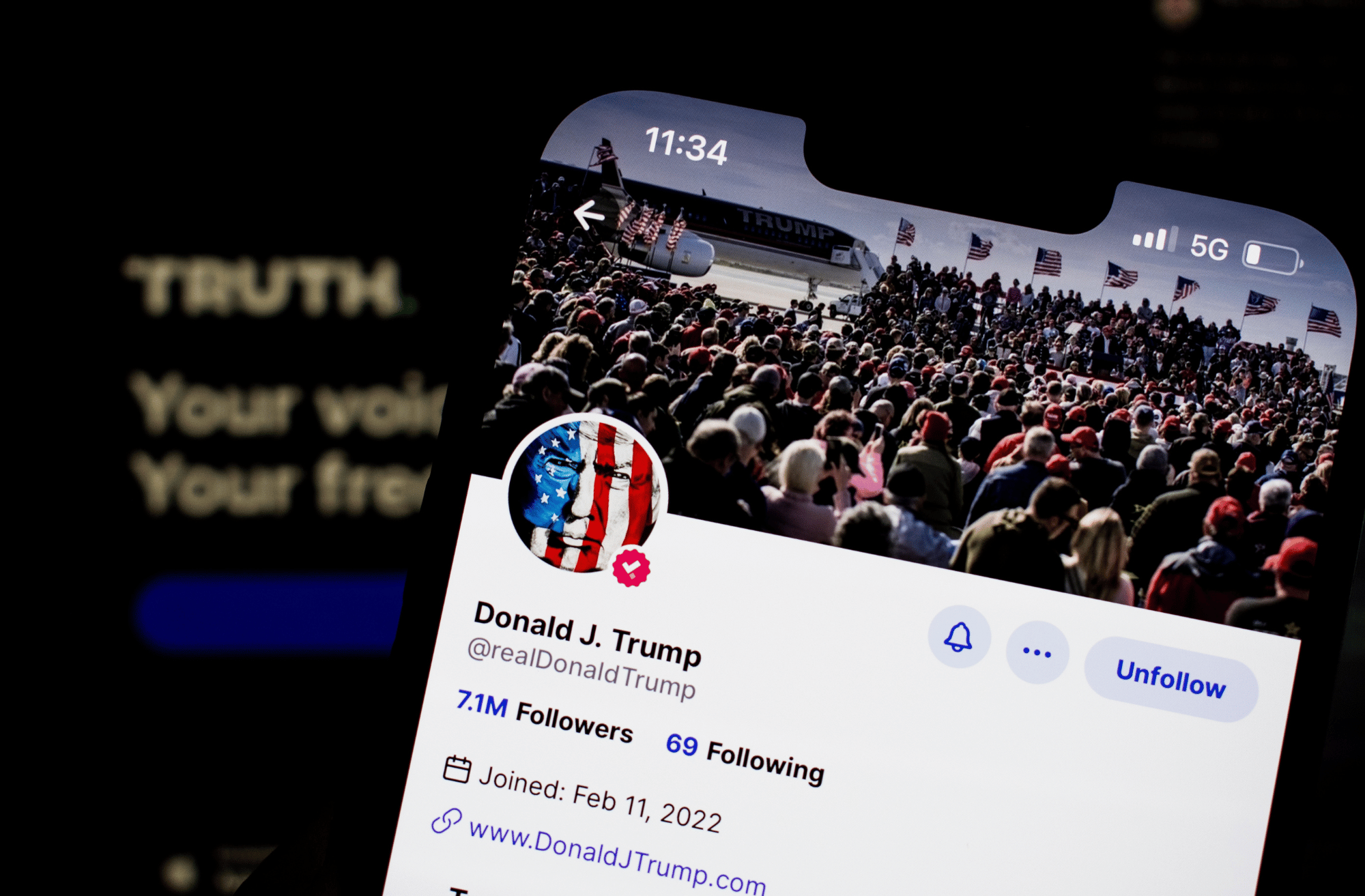

Complete disintermediation is a myth: digital platforms are themselves a new class of intermediaries. But the promise of immediacy rings true. Older intermediaries have been bypassed or rendered obsolete. Digitally mediated connections between figures such as Donald Trump or Narendra Modi and their followers are more immediate than older institutionally mediated and filtered connections between politicians and citizens. And citizens’ relation to public knowledge claims—though mediated by digital platforms like Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok—is more direct than it was when public knowledge was primarily organized by a single state public broadcaster or a few large networks.

Disintermediation is a powerfully attractive ideal, and it is precisely a populist ideal. For populism is itself an ideology of immediacy. Populism promises to empower ordinary people by disempowering mediating institutions and the elites comfortably ensconced in them. It delegitimizes political parties, professional expertise, courts, and the mainstream media and demands a direct relation between “the people” and the exercise of power.

Hyperconnectivity also fosters populism by contributing to the popularization of culture and politics. It does so in three ways. First, it opens up more accessible and engaging forms of cultural and political participation and broadens the range of participants. Digital platforms have made it much easier for those outside the cultural or political mainstream, including the disaffected citizens to whom populist politicians often appeal, to find like-minded others and establish a public presence.

Second, the digital public sphere makes calculations of popularity—and representations of what “the people” like, want, prefer, and believe—more central to culture and politics. Technologies of continuous and granular quantification render “the people” visible and knowable in new ways. Digitally mediated ways of consulting “the people” and registering their preferences have been at the forefront of digital democracy initiatives. And renderings of the popular have become central to the everyday workings of culture and politics. Ubiquitous “trending” algorithms, for example, do not simply register what is popular for a particular public at a particular moment; as Tarleton Gillespie notes, they amplify and reinforce the popularity that they register. The digitally networked public sphere thus enshrines the cardinal populist criterion of popularity as the ultimate arbiter of value.

Finally, hyperconnectivity favors popular—that is, “low” rather than “high”—cultural and political styles. “Low” styles are attention-seeking and taboo-breaking; they flout the constraints of polite speech and political correctness, and they favor confrontation, emotionalization, personalization, and hyper-simplification. Such “low” styles were already encouraged by the television-era mediatization of politics. But they are even more strongly favored in the highly competitive digital attention economy—and in what I call the “attention polity.” They have the best chance of gaining traction by breaking through the glut of digital content.

The ecology of hyperconnectivity thus has deep affinities with the logic of populism. In the cultural domain, it erodes the power of gatekeepers, engenders new forms of popular creativity, and universalizes metrics that record and amplify popularity. In the political sphere, it allows “ordinary” people—disaffected citizens in particular—to be addressed directly, it facilitates the emergence of counter-publics, and it rewards the “low” styles that are best suited to mobilizing against the establishment.

Yet at the same time, the new modes of algorithmic governance enabled by hyperconnectivity are deeply technocratic. Algorithmic governance is not restricted to governments. It is much more developed in the private sector, especially by the great tech platforms themselves. For these platforms have the data and machine-learning expertise to employ much more sophisticated forms of algorithmic governance. And they are centrally involved in the business of governing. They govern, of course, the activities of their users through their design and control of the digital architectures that determine what can be done on the platforms. But their governing power extends to public life more broadly. Most crucially, they govern who sees what, and who can say what, in the digital public sphere.

Algorithmic governance, like technocracy in general, is premised on specialized knowledge. Yet that knowledge is not embodied in trained human experts, as in traditional understandings of technocracy. Instead, it is disembodied: encoded in algorithms and generated by complex computational procedures that analyze large volumes of data—above all the digital trace data that the great platform companies effortlessly capture and exploit. The justification for entrusting decision-making to such procedures is that the knowledge they generate and their capacity to find optimal solutions for precisely defined problems are superior to the knowledge and optimizing capabilities of even the most highly trained humans.

Technocratic ideals also underlie and animate the broader spirit of what Evgeni Morozov calls “technological solutionism.” Solutionist thinking, like technocracy in general, is depoliticizing. It seeks to transform social and political problems into technical problems. It thus exemplifies the “assimilation of politics to engineering” that Michael Oakeshott saw as characteristic of rationalist politics in general.

Technocracy and populism are generally seen as antithetical. While technocracy entrusts decision-making powers to experts (or to expert-designed knowledge procedures like algorithms), populism distrusts expertise. And while technocracy is depoliticizing, seeking to insulate decision-making from popular interference, populism is re-politicizing. Populism claims to reassert political control over issues that are seen as having been removed from the domain of democratic decision-making and entrusted to unaccountable bureaucrats, experts, or courts.

Yet as Christopher Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti have argued in their book Technopopulism, the reciprocal antagonism of populism and technocracy conceals an underlying affinity: both are opposed to the complex and messy institutional mediations of party democracy. As the structural foundations of party democracy have eroded in the last half-century, political competition has come to be structured increasingly by what they call a “technopopulist” political logic, characterized by conjoined appeals to “the people” and to problem-solving “competence.”

Bickerton and Invernizzi Accetti are not concerned with new communications technologies; the “techno” in their “technopopulism” refers to technocracy, not to technology. Yet hyperconnectivity powerfully reinforces the synthesis of populism and technocracy that they describe. As a technology and ideology of immediacy, it exacerbates the crisis of institutional mediation to which technopopulism claims to respond, by contributing to the hollowing out of parties and of the press as mediating institutions. As a technology of the popular, hyperconnectivity generates new ways of mobilizing, consulting, and measuring “the people” as well as new ways of claiming to act on their behalf. And as a technology of knowledge, it affords new ways of knowing and governing the social world, and new ways of recasting social problems as technical problems. If technopopulist appeals to “the people” and to expertise increasingly “structure our politics and shape our experience of democracy,” as Bickerton and Invernizzi Accetti argue in the final sentence of their book, hyperconnectivity increasingly structures and shapes appeals to “the people” and to expertise. The “techno” in technopopulism may thus indeed refer to technology as well as technocracy.

Rogers Brubaker is professor of sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he holds the UCLA Foundation Chair. He was a guest of the IWM in 2024.