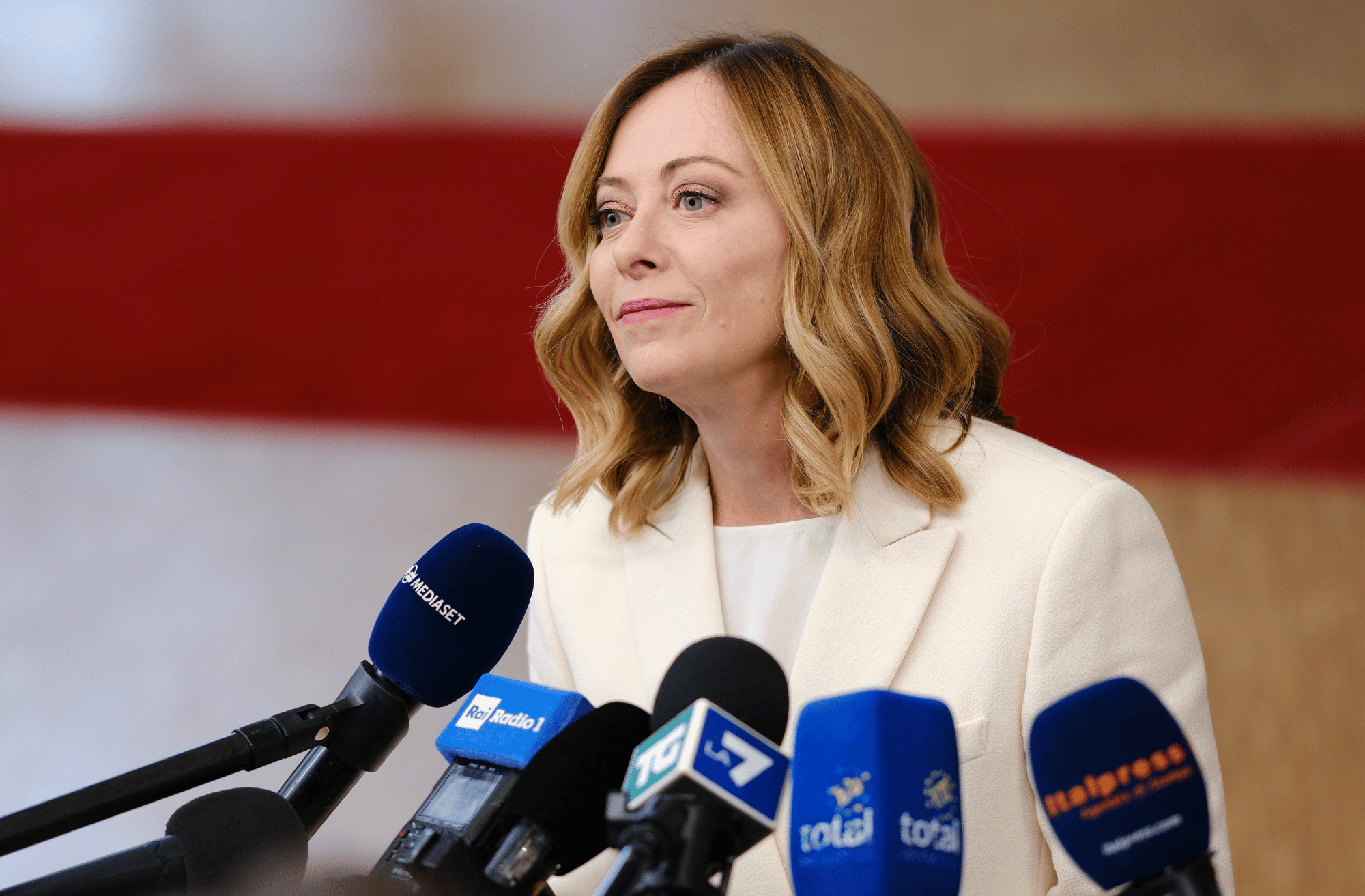

Viktor Orbán influenced Giorgia Meloni’s tactics, and his Fidesz and her Fratelli d’Italia have close connections and a common purpose, but Hungary’s prime minister can only dream about the influence she has gained in European politics. Italy’s far-right leader is Orbánizing not just her country but also the EU.

Given the illiberal playbook he used and exported, Viktor Orbán is considered to be the black sheep of the EU. Hungary’s prime minister even promotes himself as an icon of the global populist right. But what about Giorgia Meloni? In addition to also causing an illiberal drift in her country, Italy’s prime minister seems more capable of penetrating the mainstream. As well as adopting Orbán’s tactics, she has her own, more insidious strategy.

“The politics of smiles and good manners on the international stage are successful propaganda that wins over even experts.” For Nadia Urbinati, an Italian political scientist at Columbia University, it is hard to get international audiences to understand the true face of Meloni. There is a historical parallel, she argues: “In the 1930s, the antifascist intellectual and politician Gaetano Salvemini struggled to convince British and American professors and journalists that there was a dictatorship in Italy. Today a similar fate befalls us: there is a risk of an authoritarian turn. We struggle to make that clear to foreign observers who think and write that Giorgia Meloni has moderated the far right.”

Though Meloni presents herself as a “pragmatic and moderate leader,” the erosion of the rule of law in Italy shows how Orbán’s illiberal playbook is applied to other EU countries. The “Orbánization” of Italy under its far-right prime minister has become a common refrain in public debate. To keep a monopolistic control of political processes, Meloni has blurred the distinction between her government, her party, and her family. After coming to power, she named her sister Arianna as the head of the Fratelli d’Italia secretariat, with the particular role of managing the membership department.

Meloni also pushed for the “premierato” reform, which would have prioritized the executive over the legislature and handed the prime minister’s coalition a guaranteed majority of seats in it. Repression of dissent, attacks against independent journalists, the political capture of the public broadcaster, the identity crusade against the LGBTQIA+ community, and the propaganda on immigration are just some of the elements showing the influence of Orbán on Meloni.

Meloni’s entourage frequents pro-government think tanks and foundations in Budapest—such as the Danube Institute, the Mathias Corvinus Collegium, and the Center for Fundamental Rights—that are a key point of intersection for the European and American far right. Orbán’s henchmen similarly often take the stage in Rome, which is home to new conservative think tanks that are networked with counterparts in Hungary.

Nazione Futura, whose president, Francesco Giubilei, played a key role as Meloni’s government adviser, has even launched a pan-European network. He has been a fellow at Mathias Corvinus Collegium, whose chairman of the board of trustees is Balázs Orbán, the political director for Hungary’s prime minister. In 2023, Giubilei’s publisher, Historica edizioni, published La sfida ungherese. Una strategia vincente per l’Europa, the Italian version of Balázs Orbán’s The Hungarian Way of Strategy. This is only one example of a dense web of connections and mutual exchanges.

This cooperation is shaping a shared playbook and Fratelli d’Italia has adopted the same watchwords and scapegoats as Fidesz. Meloni emulates Orbán’s anti-LGBTQIA+ rhetoric and “crusades” for “demographic renewal,” and she shares his belief in the supremacy of national law over EU “impositions.” Since coming to power, she has eroded the rule of law by targeting the judicial system. As Fidesz did, Italy’s governing party is attacking independent media. Meloni has gone even further by verbally, violently, and explicitly attacking intellectuals, journalists, newspapers, and the judiciary. Students were charged by the police while demonstrating peacefully.

After the war in Ukraine began, and with the prospect of becoming prime minister, Meloni put aside the pictures with her ally in Budapest. Her priority was to show her alignment with Washington and to make public opinion forget that she is a post-fascist leader. But the close contacts never stopped: far from it.

In September 2022, a few days after Fratelli d’Italia’s electoral triumph, think tanks linked to Meloni gathered the far-right galaxy in Rome’s Hotel Quirinale. Orbán loyalists took the stage with Raffaele Fitto, Meloni’s key figure in Europe, and with Lorenzo Fontana, the president of the lower house of parliament from the Lega party, who is in close contact with Fidesz circles. Balázs Orbán attacked EU sanctions against Russia. In September 2023, Meloni travelled to Hungary to attend the Budapest Demographic Summit—and more importantly, to meet Orbán.

As the president of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) party, Meloni has presented herself a pragmatic leader who is able to talk to anyone, and as the “bridge” between the EU establishment and the untamed far right (including Orbán).

In 2021, before becoming prime minister, Meloni boycotted attempts to form a Europe-wide far-right alliance, as proposed by Orbán, Matteo Salvini, and Marine Le Pen. Sabotaging this project served her interests in two ways. It helped to negotiate a tactical alliance with the conservative European People’s Party (EPP), the dominant right-wing force in the EU, and to secure her leadership of her part of the political spectrum. January 2022 saw the first manifestation of this alliance with the election of the EPP’s Roberta Metsola as the president of the European Parliament and the ECR getting one of the vice president positions.

Most importantly, the ECR-EPP alliance broke the cordon sanitaire against the far right and opened the door to deals with it. Following subsequent elections in Finland and Sweden, EPP-led governments have been in office with the support of far-right parties.

After becoming prime minister, Meloni first downplayed her relations with Orbán and Fidesz to gain credibility while positioning herself and her party as the key player at the intersection of Europe’s right and far-right forces. Now that Fratelli d’Italia has penetrated the European conservative establishment, Meloni is making room for her long-standing illiberal teammates. More than neutralizing Orbán, Italy’s far-right leader is Orbánizing her country and the EU.

Francesca De Benedetti is senior editor at the Italian daily Domani, where she covers European politics. She was a Milena Jesenská Fellow at the IWM in 2024.