In Serbia, the hydropower sector has been used strategically for managing external pressures, building alliances, and fostering domestic elites. This continue to shape, and will likely play a role in, future struggles over the region’s environmental resources.

Extensive investments in small hydropower plants (SHPs) and the widespread protests against their detrimental socio-ecological effects marked the first wave, between 2009 and 2020, of the energy transition in Serbia. Despite its initial claims regarding sustainability and compliance with mandatory EU quotas, the government eventually cancelled new projects. The mushrooming of SHPs across the region was driven by international financing as well as by lucrative national subsidies for renewable energy. Yet, the initial purpose of the SHPs and of renewables in general was not only achieving sustainability of the sector. In the early stages of the transition, the introduction of SHPs had more to do with managing the liberalization of the state-controlled electricity market. In this context, liberalization entailed a complex package that aimed at removing state monopoly, reducing the state’s role for the benefit of private investors, and removing price controls, among other measures. The result was a change in ownership structure without explicit privatization. Renewables had a central role in this and, as a candidate country, Serbia merely followed the EU’s regulatory path.

However, liberalization has played out unevenly across the EU, even though its institutions prescribed this as a driver of the integration of fragmented national markets. The uneven realization was particularly apparent in the cases of Bulgaria and Romania, both recent member states. Under the dual pressure of EU conditionality and obsolete infrastructure, the two countries became the main investment destinations for incumbent companies from older member states, which sought opportunities to substitute for profits lost due to liberalization at home. They aimed to develop large renewable projects abroad because only subsidized renewable electricity could bring them significant and long-term gains. While older member states had greater flexibility to improvise and were able to partially carry out or even avoid liberalization, the latecomers had no choice but to comply fully and swiftly with the EU rules. Bulgaria and Romania therefore fully opened their electricity sectors to foreign investors. This dynamic resulted in the creation of EU-wide oligopolies and rising electricity prices in the two countries, which led to citizens’ disapproval, protests, and even the fall of the government in Sofia. Although praised for their rapid liberalization and decarbonization, both countries eventually halted new renewable-energy investments.

Serbian policymakers closely observed these developments in the neighboring countries, expecting similar obligations as a part of the EU accession process. My interviews with national policymakers revealed that the double transition of decarbonization via liberalization opened space for conflicts between different holders of capital, the state, and citizens. That is why I claim that SHPs were an attempt to address liberalization and these conflicts. While wind power was largely controlled by foreign investment funds, policymakers envisioned SHPs as an opportunity for carving out space for domestic capital in the sector. The economic and technical capabilities of SHPs were particularly suitable for that purpose. Hydropower was cheaper than new renewables because its technology was established, more rudimentary, and thus less costly, and there were experts available in the country. A large portion of the costs was for construction, and only one or a few plants were enough to make the business profitable. Economy of scale was therefore much less important than with large wind parks. Finally, since SHPs were more dispersed, their effect on the grid was minimal, which meant that the necessary upgrade was more limited.

All these factors made SHPs an attractive option for the state and domestic capital. Yet, it would be too simplistic to think of this as a policy solution to reject the influence of external forces. Rather, it was a project for building a domestic capitalist base and aligning it with the political elite, while gradually opening the energy sector to foreign capital and complying with EU regulations.

Forging Regional Alliances Through Hydropower

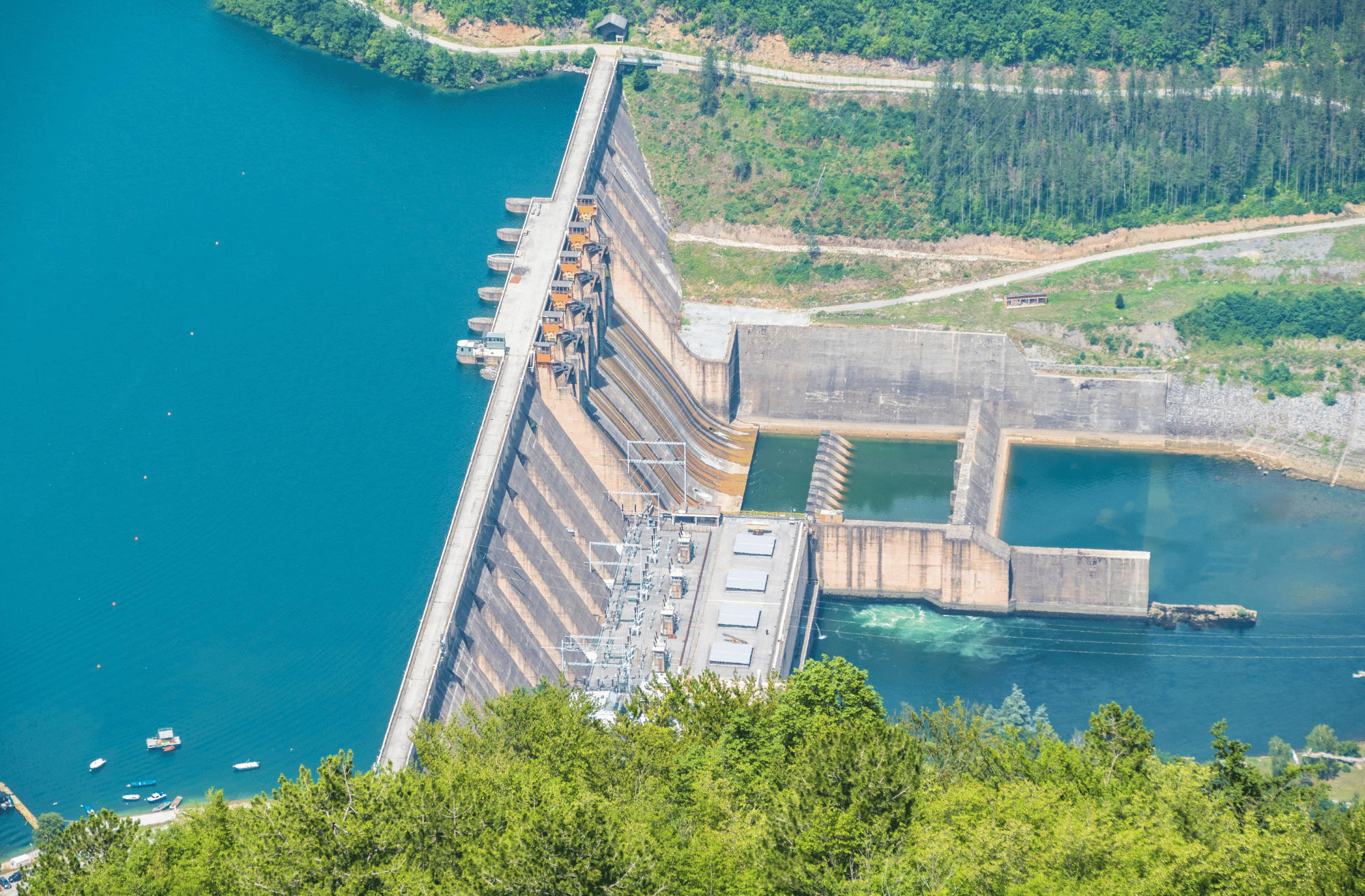

A recent proposal for a joint venture between the Serbian public company EPS and its Hungarian counterpart MVM offers another perspective on using hydropower infrastructure, this time for regional integration. The plan envisioned that EPS would transfer ownership of 11 large Yugoslav-era hydropower plants to the new company. On the list was the “hydropower pearl”: the Bajina Bašta reversible pumped storage. This plant is valuable because, in the absence of affordable and effective large battery storage, reversible plants remain the solution for storing electricity. They not only store energy but also help manage the variability of solar and wind power in a carbon-neutral way. The value of such energy on the international market is significant. However, the EPS management rejected the proposal due to public criticism that a “ silent privatization” was underway. The EPS management was soon “professionalized”—replaced by a board of foreign managers—and a similar proposal may appear, especially since Hungary recently joined a Serbian-Slovenian regional power-exchange platform.

This example illustrates how energy infrastructure fulfills multiple, sometimes even contradictory, purposes—reconciling diverging interests while appearing as a purely technical issue. The EPS-MVM proposal did not oppose the EU market model but rather built on it. It used the principle of regional market integration to forge a political alliance extending beyond technical cooperation and market exchange.

Novel Tendencies in Regional Energy Politics

Any claim of political novelty in the deployment of the hydropower sector as described above is questionable given the long history of socialist cooperation and nonalignment that relied on Yugoslav energy infrastructure. Yet, some new tendencies are hard to ignore.

The two cases looked at suggest that there might be a growing permeability between liberal governance and state roles, with authoritarian regimes coopting a liberal policy repertoire to strengthen themselves, as seen with SHPs. The domestic capitalist base developed over the last decade might play a key mediating role in such an arrangement, linking the state with key international actors and channeling resources between them.

Another tendency is the institutionalization and solidification of the regional scale as a type of geopolitical sub-grouping. This regional approach is based not only on proximity (which is important for electricity infrastructure) but even more on political and economic agendas and on positioning “within-and-between” blocs. We can observe some attempts at such positioning by Hungary and Serbia. Unfortunately, this will likely be predicated on a constant search for stakes and resources that will produce new sorts of dispossession, violence, and control. As the importance of labor, carbon-neutral energy, and raw materials increases in geopolitics, Serbia’s regime will likely employ them to make a place for itself “within-and-between” geopolitical rivals.

Dragan Ðunda is a doctoral student in sociology and anthropology at the Central European University. He was a SEE Junior Fellow at the IWM in 2023–2024.