At the beginning of the twentieth century, the illustrated poetry book emerged as one of the Yugoslav avant-garde’s favorite ways of expression. Its subversiveness was supported by the text and by its illustrations. But when the unruly avant-garde got absorbed into the literary canon after the Second World War, the illustrations—curiously—went missing from the reprints.

The interplay of text and pictures is as old as the script itself. It is most evident in the long-standing tradition of illuminating scriptures and illustrating books. However, the seemingly simple question of whether an originally illustrated book remains the same once its illustrations are removed is a very intriguing one. This is especially true when it comes to works that use the interplay of the textual and the visual, as is the case with the Yugoslav avant-garde illustrated poetry books.

The historical avant-garde consists of a group of experimental and innovative artistic and cultural movements—such as Expressionism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism—that emerged primarily in the early twentieth century and between the two World Wars. Their desire to challenge established norms and traditions in art and society was usually conveyed by radical and unconventional techniques. As in the rest of Europe, the Yugoslav historical avant-garde established itself in the interwar period, in the time of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which adopted the name Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. One of the fascinating outcomes of its confrontation with traditional media practices and ways of representation can be observed in the illustrated poetry books. These predominantly originated as a result of a collaboration between a poet and a visual artist. In this way, their distinctive intermediality was established and expressed in the dynamic coexistence of the verbal and visual elements.

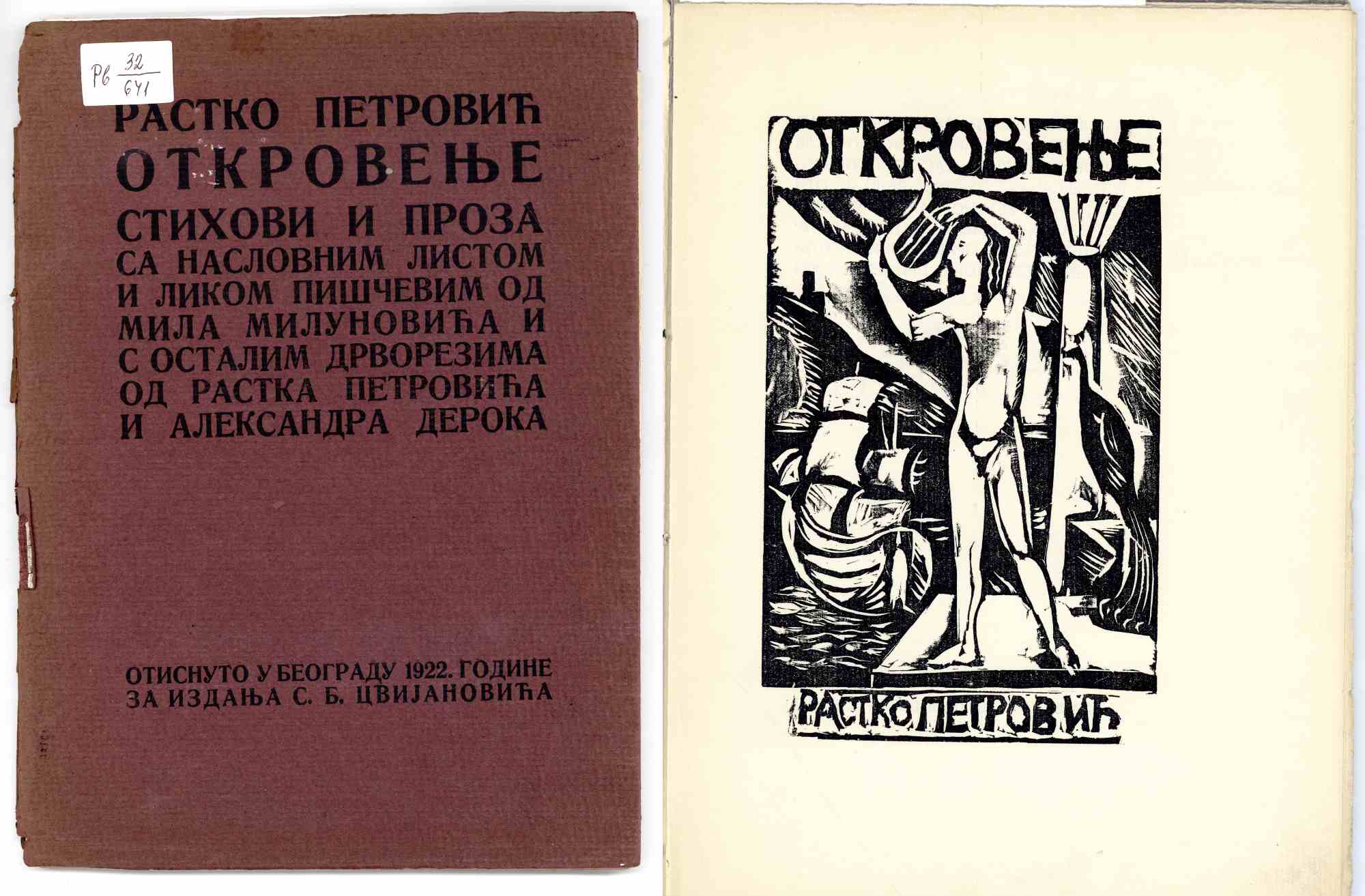

Typically for the avant-garde, the two elements in Yugoslav illustrated poetry books, each on their own, defy prevailing literary and artistic norms. The texts within them are not exclusively lyrical poems written in verse. Much more often than not, the textuality of these books challenges and transcends the genre conventions: it usually shifts from verse to prose and back, as in Milan Dedinac’s Javna ptica (1926). When it comes to the visual elements, their variety in terms of production technique is immense. It entails drawings and technical-like graphs and charts, like in Marko Ristić’s Turpituda (1938) or Moni de Buli’s Iksion (1926). It stretches even further to diverse types of graphics, such as woodcuts in Rastko Petrović’s Otkrovenje (1922), and to photographs and photo-montages, as in Dedinac’s Jedan čovek na prozoru (1937) and Aleksandar Vučo’s and Dušan Matić’s Podvizi družine “Pet petlića” (1933).

However, what really generates the subversive potential is the inclusion of these visual materials within poetry books. As a consequence of this, varied and complex relations between texts and pictures arise. These relations can be regarded from the perspective of the functions the textual and the visual elements perform in respect of each other. In Dedinac’s Jedan čovek na prozoru, poetic text and inserted photographs each function as substitutes for the other to compensate for their “lacks” in terms of their representational possibilities. Or, as is the case in Petrović’s Otkrovenje, the woodcuts function as a unifying device that structurally reinforces the layout of the book. Hence, the function of the illustrations in the Yugoslav avant-garde illustrated poetry books is not only what one might assume based on the traditional understanding of the term “illustration”: a simple graphic paraphrase of the text.

The aftermath of the Second World War brought significant changes to the Yugoslav avant-garde illustrated poetry books. In the times of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, and later in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, they were reissued and republished on various occasions and in different ways. In most cases, however, the pictorial elements were drastically altered, as in Podvizi družine “Pet petlića,” or entirely eliminated, as in Otkrovenje.

This was mostly done by the editors of the reissued publications and, after the war, many avant-gardists had gained prominent positions in editing houses. Thus, in some cases it was the poets themselves who edited their own books or those of others. The interwar oppression and dictatorship of the monarchy had ceased, and consequently the need for avant-garde rebellious activities and expression disappeared. What is more, the ideas and values represented and promoted in the avant-garde works were supported by the emerging Yugoslav state. The illustrated poetry books, once highly revolutionary, were adjusted to the new cultural and political paradigm. Moreover, the suspension of their intermediality got them ready to fit into the literary canon as some of the works were reissued and republished as mandatory school reading. Thus, for example, provocative photo-montages were replaced with simplistic drawings more appropriate for children and fitting the uniform look of school books.

Does an illustrated poetry book remains the same without its illustrations? The answer depends on the understanding of the term “book.” If we understand the book as the metonymy of written words, then the removal of illustrations does not affect its authenticity and meaning. But when a book is considered a unique object for its content and materiality alike, as well as for the way of its production, then even minor modifications, let alone removing illustration, profoundly impact its meaning and the possibilities for its interpretation. This is particularly significant where the interplay of the textual and the visual is the ground for the book’s subversive agency. Stripped of this kind of potential and sometimes even reduced to mere text, the Yugoslav avant-garde illustrated poetry books became “only” poetry books.

For these reasons, studying the intermediality in Yugoslav illustrated poetry books requires diachronic and synchronic approaches. The former permits an exploration of historical shifts in intermedial practices within these books, while the latter allows for the concrete analysis of the intermedial products and the interplay of their verbal and visual content. The relations between the text and pictures, however, need to be problematized. Otherwise, one could easily fall into a simplified comparison between the visual and the verbal content.

Therefore, starting from the premise that written text as a form of verbal representation inherently contains something of the visual through the materiality of the script, same as visual representation is always already contaminated with some sort of discourse, the constant interplay between the two modes of representation in the illustrated poetry books comes to the fore. This suggests that illustrated poetry books exhibit a multiplication of the relationships between the verbal and visual aspects. On the one hand, the interaction between the two is viewed as an integral element in the makeup of illustrated poetry books. On the other hand, each participating media inherently incorporates their interplay.

Yugoslav illustrated poetry books exemplify a fascinating intersection of interwar and post-Second World War artistic expression. They convey diverse aesthetic and political ideas, while their intermediality was eventually subjected to negotiation by alteration and elimination of the pictorial elements. Today, these books need to be re-examined. But this time, the constant interplay between the verbal and the visual needs to take center stage. Only this will lead to a nuanced understanding of their complexity and the interconnectedness of their constitutive elements. Finally, it will tell us more not only about the processes taking place in the background of the taming of the Yugoslav avant-garde, but it could also provide insights into contemporary intermedia phenomena.

Tijana Koprivica is a PhD candidate in Slavic studies at the University of Vienna. She was a fellow of the Southeast European Graduate Scholarship Program at the IWM (2022–2023).