Popular at the turn of the twentieth century, the Austro-Marxist idea of non-territorial autonomy for national minorities was relegated to a dusty corner of history for decades after World War Two. Lately, it has been experiencing a revival.

“The idea of non-territorial national autonomy, despite being widely recognized theoretically, is not acceptable in practice to those who are not used to it,” wrote Max Laserson in a Latvian newspaper in 1922. A century later, the sentiment expressed by the Latvian-Jewish parliamentarian, who was a staunch proponent of the idea, still rings true. Despite a steadily growing body of literature on non-territorial autonomy (NTA) from the end of the nineteenth century to the present, it is still often perceived by the wider public as a mothballed intellectual curiosity rather than a blueprint for solving the dilemma of ethnic diversity in a world of nation-states.

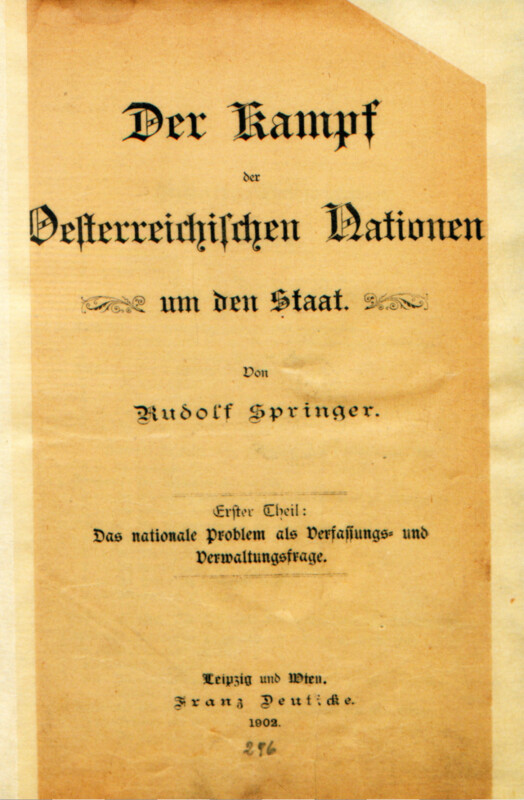

The idea of NTA, which attempts to separate the notions of nation and territory by granting self-governance in cultural and educational matters to national groups regardless of their territorial settlement, has many ideological antecedents. It was most comprehensively articulated in the works of the Austrian social democrat Karl Renner (1870–1950) at the turn of the twentieth century. His Staat und Nation (1899) and Der Kampf der Österreichischen Nationen (1902) were widely read in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond, circulated primarily through socialist channels. Seemingly holding the promise of solving the nationalities question while sparing territorial borders, NTA quickly became, as the historian Gerald Stourzh put it, “tantamount to a magic word.” Numerous political parties in the multinational Habsburg and Russian Empires made national autonomy, in its territorial or non-territorial form (or, often, in a combination of the two), part of their programmes and manifestos, while many nascent national movements claimed it as their sole raison d’être. The advocacy for NTA was particularly strong on the part of Eastern European Jewish minorities, with the Russian Jewish historian Simon Dubnow (1860–1941) coming up with his own theory of Jewish autonomism.

As debates on the future of Central and Eastern Europe intensified during World War One, the idea of national collectives as legal entities with autonomous agency in cultural affairs was seemingly only gaining strength. After the February Revolution of 1917, the federalist projects of all liberal and socialist parties within Russia included autonomy in one way or another. The Bolsheviks, who came to power in November 1917, famously rejected NTA outright—however, in practice their territorial approach to the nationalities question was often complemented by non-territorial arrangements.

Minority rights came sharply into focus once a wave of pogroms broke out across Central and Eastern Europe at the close of the war, making everybody wonder whether the newly minted nation-states could rival the late Russian Empire in its proverbial antisemitism, and whether additional safeguards were required for minorities. In 1918, on the eve of the Paris Peace Conference, Renner published Das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Nationen, an expanded and updated edition of his 1902 book. Renner’s theory was vividly discussed in Paris behind the scenes by those who were tasked with solving the nationalities question and those who strove to advise them. However, the perceived “Germanic” origins of the idea of NTA caused certain misgivings early on. These suspicions were later aggravated by the fact that, throughout the interwar period, in Central and Eastern Europe NTA was championed by the German minorities, along with the Jews. In the words of the historian Mark Mazower, these “two great minorities of 1918” spearheaded the struggle for minority rights between the world wars, often joining forces domestically and internationally.

The contribution of the Jewish lobbying delegations at the Paris Peace Conference to the formulation of minority rights in the subsequent Minority Treaties that were placed under the guarantee of the League of Nations, thus creating the first-ever international regime of minority rights, is widely recognized by historians. But when it came to the issue of national autonomy for minorities, these delegations were deeply divided. While the Eastern European Jews advocated for autonomy and the Americans, especially the newly created American Jewish Congress, supported them in their demands, the French and British Jews insisted that Eastern European ones should, like them, strive only to become equal citizens of their respective states. Eventually, a compromise was reached, and the Jewish memoranda submitted to the peacemakers asked not just for minorities’ equal civil and political rights and nondiscrimination on the grounds of race or religion, but also for the autonomous management of their religious, educational, charitable, and other cultural organizations. In the end, the words “autonomy” or “autonomous” did not make it into the treaties. However, the stipulations on minority schooling, albeit couched in different terms, came quite close to the Jewish demands. But, importantly, these rights were extended to individuals belonging to national minorities but not to the national collectives.

Nevertheless, a number of new nation-states promised NTA to their minorities in their independence proclamations. During the interwar period, it was implemented in the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918–1921), the revolutionary Upper Volga Region, Siberia, and the Far Eastern Republic. NTA flourished in democratic Lithuania from 1919 to 1922. In Latvia, the de facto NTA provisions for minorities were in place from 1919 until 1934. In the most celebrated case, a fully-fledged NTA for minorities was realized in Estonia from 1925 to 1940. On the international scene, the Congress of European Nationalities (1925–1938), a common body of minorities that in its heyday represented twenty ethnic minority groups from fifteen states, made NTA a cornerstone of its programme. In 1929, emboldened by the success of NTA in Estonia, it called—unsuccessfully—on the League of Nations to replace the existing Minority Treaties with “a genuinely pan-European guarantee of minority rights” based on the NTA model.

It was perhaps the infamous demise of the Congress of European Nationalities, which in the late 1930s became subverted by the Nazis, and of the League of Nations, together with the minority rights regime it underpinned and the entire international order it represented, that relegated NTA to a dusty corner of history. After World War Two, the focus shifted decisively toward individual human rights and away from minority rights. Until very recently NTA remained a largely forgotten, antiquated notion.

But with the collapse of the socialist bloc in Europe in the late 1980s, new national minorities emerged, and old and new methods alike were required in order to deal with the newly salient ethnic diversity. Since then, interest in NTA has been steadily growing among academics and practitioners. Elements of it, in different forms and guises, are present in various diversity-accommodation mechanisms around the world, and they can also be found in minority-protection legal mechanisms. As a group-rights-based approach to diversity, NTA has assumed a prominent place in the debates between individualists and communitarians, highlighting the drawbacks and the advantages of the model in a world of nation-states. Contrary to earlier assumptions, the jury is still out when it comes to the future prospects for NTA.

The research for this essay was supported by funding from the European Research Council within the project “Non-Territorial Autonomy: History of a Travelling Idea,” Grant Agreement No. 758015.

Marina Germane is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for East European History at the University of Vienna. She was a guest of the IWM in 2023.