Sigmund Freud had to flee Vienna in June 1938 under dramatic circumstances. In postwar Austria he gradually became the city’s valuable brand, tourist asset, and pop icon. American intellectual historians facilitated this transition, which also resonates with a globalized vision of the 20th century as “the century of the self.”

After the annexation of Austria by the Third Reich on March 13, 1938, Sigmund Freud was finally convinced by his colleagues to leave Vienna, which he had stubbornly refused to do. His rescue turned out to be an international operation, and he was allowed to leave Vienna on June 4, 1938.

Freud moved to London, where he died three weeks after the beginning of the Second World War. His fellow psychoanalysts, particularly those of Jewish origin, left continental Europe en masse and settled mostly in the United States. Psychoanalysis was embraced by important parts of the American cultural mainstream, which secured a high academic and social position for psychoanalysis in the United States, but its medicalization and masculinization had a price—and a quite high one, at that. As Russell Jacoby noted in 1983, the Freudians of the first two generations were “cosmopolitan intellectuals, not narrow medical therapists. Compared to recent American analysts, they represent another species.”

Increased democratization of American society brought harsh criticism of American psychoanalysis, which undeservedly became synonymous with Freudianism. In this way, Freud was accused of elitism, phallocentrism, and Eurocentric views. Elements of all these unavoidably exist in Freud’s writings as the hallmarks of his zeitgeist. He was, however, predominantly a humanist, intensely focused on finding ways to liberate humanity from its legacy of cultural and sexual repression, and the liberation was meant for all and was certainly not limited to American white men of the middle and upper classes.

The postwar situation in Vienna was radically different than that in the United States. The city where psychoanalysis was born could not really focus on Freud during the early years of rebuilding. Interest was limited to groups of dedicated followers, who were divided into two associations. It took 20 to 30 years for Freud’s legacy to begin finding its place in Vienna and Austria.

Among his children, only Anna Freud went into psychoanalytic practice. She was the key person to be approached about a possible Freud center or museum in Vienna but, as her biographer Elisabeth Young-Bruehl put it, “she had consistently refused any public connection with Germany or Austria.” It was the idea to establish a museum in the city that convinced her to change her stance. In her reply to its mayor, she thanked him for supporting this project and expressed her “Freude und Genugtuung [joy and satisfaction/reparation],” and the ambivalence of the second word was noticed already by her biographer. The Sigmund Freud Museum opened in 1971, when Anna Freud made her first visit to Vienna, 33 years after her exile.

Since the early 1960s, Freud’s intellectual achievement has been seriously studied and admired by leading American intellectual historians. Carl E. Schorske’s brilliant studies were published in succession from 1961 and collected in his famous book Fin-de-siècle Vienna (1980). He identified Freud as one of the leading persons of early 20th century Vienna but also as one who “long since established himself as a major figure in American thinking.” William M. Johnston went one step further. In 1972, he published his much acclaimed and penetrating book The Austrian Mind. Out of more than 70 persons of prominence, who had all contributed to the distinctive intellectual climate of Vienna, Freud was the only one to be the subject of three chapters, and Johnston made it clear who had made the most decisive mark on posterity. “First place undoubtedly must go to Freud. No other thinker of the twentieth century, Austrian or otherwise, has so impregnated contemporary consciousness, permeating every facet of economic, social, and intellectual life.” The renewed interest of top American intellectual historians corresponded with and reinforced a renewed intertest in Freud in Vienna.

Freud as a Viennese Cultural Hero and Pop Icon

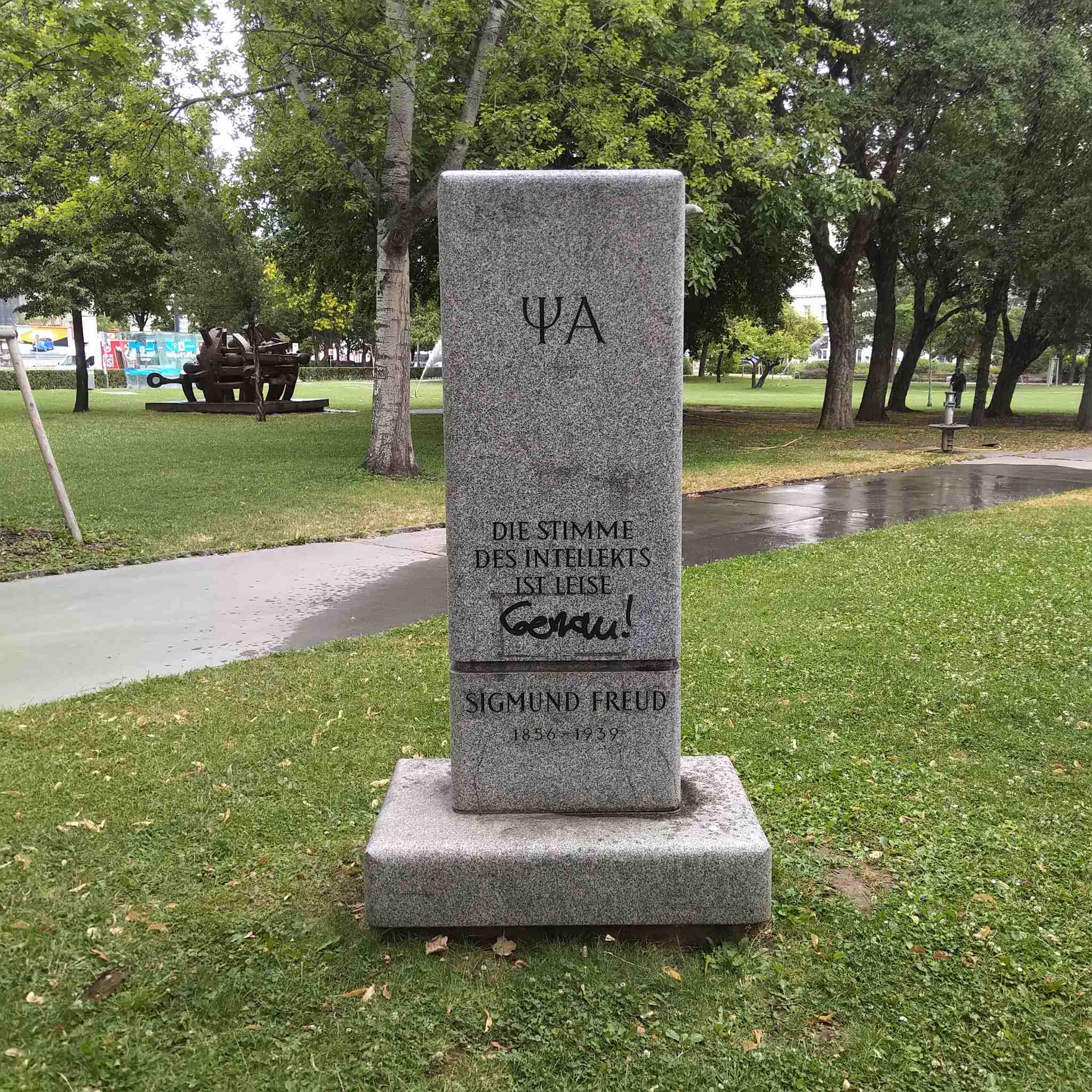

After the opening of the museum, other places in Vienna followed suit in acknowledging Freud. In 1984, the park in front of Hotel Regina was renamed Sigmund Freud Park. The following year, a memorial stone to psychoanalysis was unveiled there. At the end of 1987, a new series of 50 schilling banknotes had Freud’s portrait. Finally, in 2018, on the 80th anniversary of his exile, Oscar Nemon’s statue of Freud was unveiled on the grounds of the Medical University. On that occasion, the university’s rector, Markus Mueller, acknowledged “our responsibility as the Medical University of Vienna for the expulsion of this outstanding scientist,” while the head of the Department of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy, Stephan Doering, proudly mentioned that Freud was “Austria’s most frequently cited researcher, with a Hirsch-index of 282.”

By the end of the 20th century, Freud was branded as one of the most illustrious citizens of Vienna ever. Major museums have also redefined his role. The permanent exhibition at the Jewish Museum at Dorotheergasse pays as much attention to Freud as to Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism. In addition to his portrait by Wilhelm Krausz, Freud figures designed for popular culture are also exhibited.

The Leopold Museum displays a showcase dedicated to his “groundbreaking work” The Interpretation of Dreams. The main exhibition, opened in 2019, is entitled “Vienna 1900. Birth of Modernism.” It clearly links Freud’s discovery of the unconscious and the emergence of new art in Vienna around the turn of the century, and it is very much based on the narratives first established by Schorske and further elaborated in Eric Kandel’s book The Age of Insight (2012). Freud does not only feature as one of the main “modernizers” in the museum; he is also the central figure on the exhibition’s placard and prominently present in the gift shop through various mass-consumption souvenirs.

It is, however, the Sigmund Freud Museum that has played a pivotal role in spreading awareness of Freud in Vienna, Austria, and beyond since its foundation. In 2020, it was renovated and expanded. The visitors entering the building at Bergasse 19 may now see a panel titled “Sigmund Freud—Breaker of Taboos.” The new exhibition is much more appealing to younger generations, and is very carefully made to cover various aspects of his life, including sensitive issues that feminist and other critiques have had about psychoanalysis. However, it also contains a section on Freud’s correspondence with Albert Einstein from 1933. While the text of the new exhibition insists on the sentence “We are pacifists”, it intentionally omits another message of the letter—that war was “scarcely avoidable.” This message of Freud could be seen as a warning that reverberated soon after the letter was written and continued to do so so to this day.

The rise of Freud as a pop icon of Vienna has been concomitant with the emergence and development of pacifist postwar Austria. It was culturally framed by American intellectual historians (Schorske, Johnston, William McGrath, Peter Gay), later joined by a neuroscientist (Kandel) and psychiatrist (George Makari )—all of whom portrayed Freud and the Viennese intellectual climax as inseparable. They have all contributed to the new contextualizations of Freud that have survived various attempts by scholars to hypercritically dismiss the Freudian legacy. As Gay aptly summarized Freud’s achievement in Time magazine in 1999, “For good or ill, Sigmund Freud, more than any other explorer of the psyche, has shaped the mind of the 20th century.”

An exile from Vienna became half a century later a symbol of the city about which he had been deeply ambivalent. Some psychoanalysts might argue that this reappraisal of Freud in his hometown may be interpreted as an expression of the Genugtuung of the Viennese: satisfaction that such a celebrity had lived in the town, coupled with a need for reparation stemming from a sense of guilt. In a global context, it may also be viewed as an acknowledgement that “the century of the self”, as the BBC once described the 20th century, marked by Freud and Freudianism, still haunts us. Some of the best tools to understand it are still those conceptualized by Freud, his followers and renegades, many of whom were also Viennese.

Slobodan G. Markovich is a professor and head of the Centre for British Studies at the University of Belgrade. He was a Krzysztof Michalski Fellow at the IWM in 2023.