What does it feel like to live in an age of perpetual technological transformation? Like losing something that only technology can help to restore.

In 1980, the American writer George Trow published a long and peculiar essay in The New Yorker titled “Within the Context of No Context.” It was obliquely about television, for it was through television that he detected a change in the “movement of history.”

The direction of the movement paused, sat silent for a moment, and reversed. From that moment, vastness was the start, not the finish. The movement now began with the fact of two hundred million, and the movement was toward a unit of one, alone. Groups of more than one were now united not by common history but by common characteristics.

“Television is a mystery,” Trow conceded, but one thing was certain: “It has a scale.” The inferential statistics behind television broke audiences down into characteristics inhabiting a theoretical multidimensional space, separated these characteristics from the contexts that gave rise to them, flattened them to groups of points within a single dimension, and then fed them back, cleansed of experience, to audiences in the form of advertising and programming. “Do you go from house to house—houses formed into little units, constituting parts, then, of larger units, which are, in turn, parts of larger units,” Trow wondered of the method behind what appeared on a television screen, “Or do you start instead with the two hundred million and slice it up? There’s a difference.” The difference was palpable, but difficult to describe. Today the scope and application of what troubled Trow is broader still. “Your audience is online, in the billions,” promises a company that uses “industry-specific vertical AI” running on an “audience demographics platform.” It goes on: “Map the audience demographics behind each conversation using interests, affinities, personality traits and buying habits. Segment your audiences by affinity to better predict behavior.”

Even a decade and a half later, with the republication of the essay in book form, Trow still struggled to express what “Within the Context of No Context” was really about and to make sense out of the “informed confusion” of the original essay. “I think I was trying to raise a hue and cry,” he concluded. “I think I was saying, ‘THE TWENTIES ARE COMING, THE TWENTIES ARE COMING.’ I think I was right; the 1920s were in the wings, then.”

*

In Virgina Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, the title character muses: “I rise through the air; I listen to voices in America; I see men flying—but how it’s done, I can’t even begin to wonder.” A technology is the culmination of a million labors over generations and of knowledge about the use of tools; it is about timing, coordination, technique, learning, knowledge itself. Once built into a machine, all that history becomes invisible, collapsed into a few visible controls. As Karl Marx put it in Capital, “The process disappears in the product.” We see neither how it works nor what went into making it work.

What is more, the machine can be picked up and moved and made to work somewhere else, under a different sun to different ends, alienated from the processes and figures that gave rise to it. The machine is nowhere—or everywhere—at home. Like a late-stage or defunct empire of the sort that littered the geopolitical landscape of the 1920s, the machine is at once the whole of the thing and the dead hulk and empty operation of the thing.

The French poet Paul Valéry, writing from such an empire in 1925, saw interaction with machines as analogous to the brain on drugs: “The more useful the machine seems to us, the more it becomes so; and the more it becomes so, the more incomplete we are, the more incapable of doing without it. There is such a thing as the reciprocal of the useful.” Soon thereafter, in the former imperial capital of Vienna, Sigmund Freud wrote his famous 1929 work Civilization and Its Discontents. Though we owe much to “the era of scientific and technical advances,” he conceded, “most of these satisfactions follow the model of the ‘cheap enjoyment’,” comparable to “putting a bare leg from under the bedclothes on a cold winter night and drawing it in again.” This fickle rush was registered by Trow, too, in connection with television. “The charm lasts just for a moment, but it does last for a moment and is powerful in that moment. A slot machine is interesting, for example, and a con man spinning a story. These things create a context. It’s like home, but just for a moment.”

*

How is it that the 1920s seem to come round and round again? And why does it feel nonetheless so disorienting each time they do? Perhaps because technology cements the results of past learning, such that anyone alive tends to possess a growing mass of obsolete knowledge and experience: how to use a phonebook or a floppy disk, read a map, or adjust an antenna. The first time the 1920s happened, Valéry wondered whether he was observing a “crisis of intelligence” as it seemed “the world is becoming stupid.” In a subsequent iteration, adeptly rendered in a short story by the Ecuadorian writer Alicia Yánez Cossío 1975, the narrator describes a smallish, all-knowing device called the IWM 1000 that is “an extension of the human brain. Many people would not be separated from it even during the most personal, intimate acts. The more they depended on the machine,” it seemed, “the wiser they became.” Before long, however, “They did not know how to read or write. They were ignorant of the most elementary things.”

Our supposedly unique human ability to “learn to learn” is deployed almost wholly in the realm of redefining a relationship between ourselves and the latest technology that has not only rendered our earlier skills, social relations, and the interactions they engendered null and void, but also frozen and multiplied the errors and oversights that underpinned those skills and relations. This is what “problem-solving” looks like here on the ground: it means solving the problems created by a previous attempt to solve a problem. Whether we choose to call this frenzied activity “progress” or not, we are forced to acknowledge its momentous force. For Marx, jumping into the scrum of inexorable industrial automation was not so much a path to utopia as a necessity of survival. In 1978, the Czech dissident Vacláv Havel observed how people on both sides of the Iron Curtain were “being dragged helplessly along” by “the automatism of technological civilization and the industrial-consumer society.”

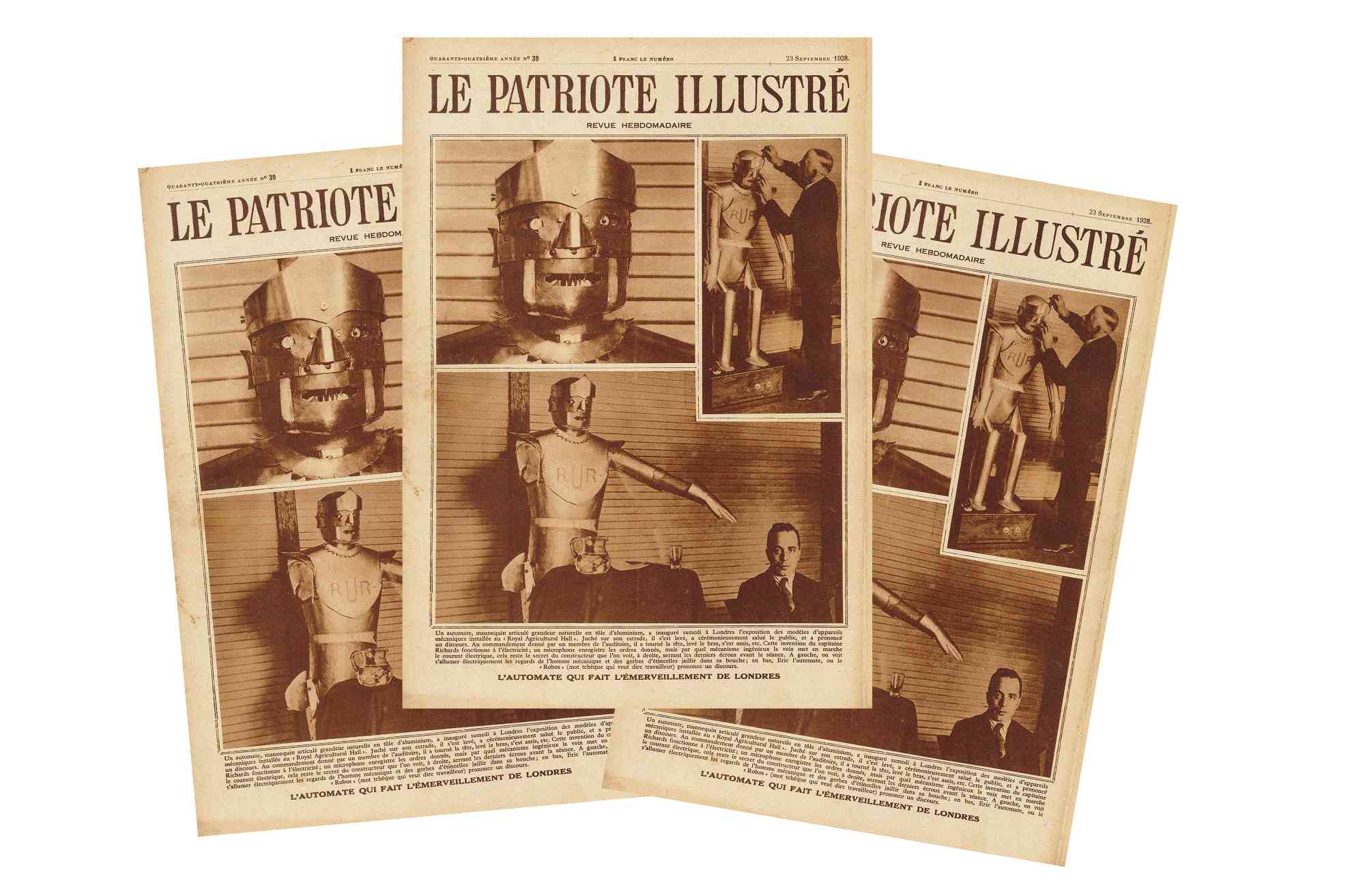

Karel Čapek, the Czech writer who coined the word “robot” in his 1920 play R.U.R., imagined an industrialist holding forth on how “The word ‘fabrication’ is derived from febris, and it means ‘feverish activity.’ […] the task of industry is to process the whole world. The world must become a factory!” To that end, the industrialist says, he employs “chosen people,” the castoffs of society, and—depriving them of human connection, friendship, and family feeling—he turns them effectively into soulless machines. “Every one is like a separate cell in a battery.” Valéry spoke in similar terms of “the monstrous scale of one man per cell.”

*

In 1921, as Čapek’s play hit stages across Europe and elsewhere, there was lively commentary and debate surrounding the proper way to interpret the story of robots designed for factory work becoming more human even as they destroy humanity to take over the world. Was it an allegory of revolution? Or of the battle of the sexes? Or of technological hubris?

Only in 1923 did Čapek declare that none to date had correctly identified the play’s true substance. R.U.R., he insisted, was on the one hand a “comedy of science” and on the other a “comedy of truth.” It was a comedy of science because “this terrible machinery must not stop, for if it does it would destroy the lives of thousands. It must […] go on faster and faster, even though in the process it destroys thousands and thousands of lives.” And it is a “comedy of truth” because all the various conflicting attitudes toward the problem and motives for action represented by the various human characters in the play are in some sense true. “In the play, the factory director Domin establishes that technical progress emancipates man from hard manual labour, and he is quite right,” Čapek wrote. “The Tolstoyan Alquist, to the contrary, believes that technological progress demoralizes him, and I think he is right, too.” Welcome to the 1920s.

Holly Case is professor of European history at the Brown University and recurrent visiting fellow at the IWM.