The West is on everyone’s lips, but what exactly is it? Where is it? When did the term begin to be used as a sociopolitical concept? More importantly, why? Who belongs to it? How many definitions of the West are there? Are they all valid? Is the West a perennial entity with an unchanging essence, or is it a mutable entity, a flexible, changeable narrative—in other words, an idea?

The “West” first acquired a political meaning as a term at the end of the 4th century CE when the Roman Empire was divided into its eastern and western parts. The Western Roman Empire was soon after conquered by waves of Germanic invaders. Although in 800 Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans, he was in practice spoken of as emperor of the West, given that there was the Eastern Roman Empire ruled from Constantinople (later called the Byzantine Empire). Thus the West was frequently used as a historical term in the 18th century to describe the successor states, kingdoms, and principalities that emerged from the ruins of the Western Roman Empire and claimed its legacy.

But this was not the same thing as what we mean by the West today. It did not refer to a contemporary supranational community or a plan for any future alliance or federation. When West-Europeans talked of themselves as a supranational community of peoples who shared a common culture and, some of them thought, should join in a federation of some sort, the name they used for this was Europe or Christendom, the latter used before the former or sometimes simultaneously.

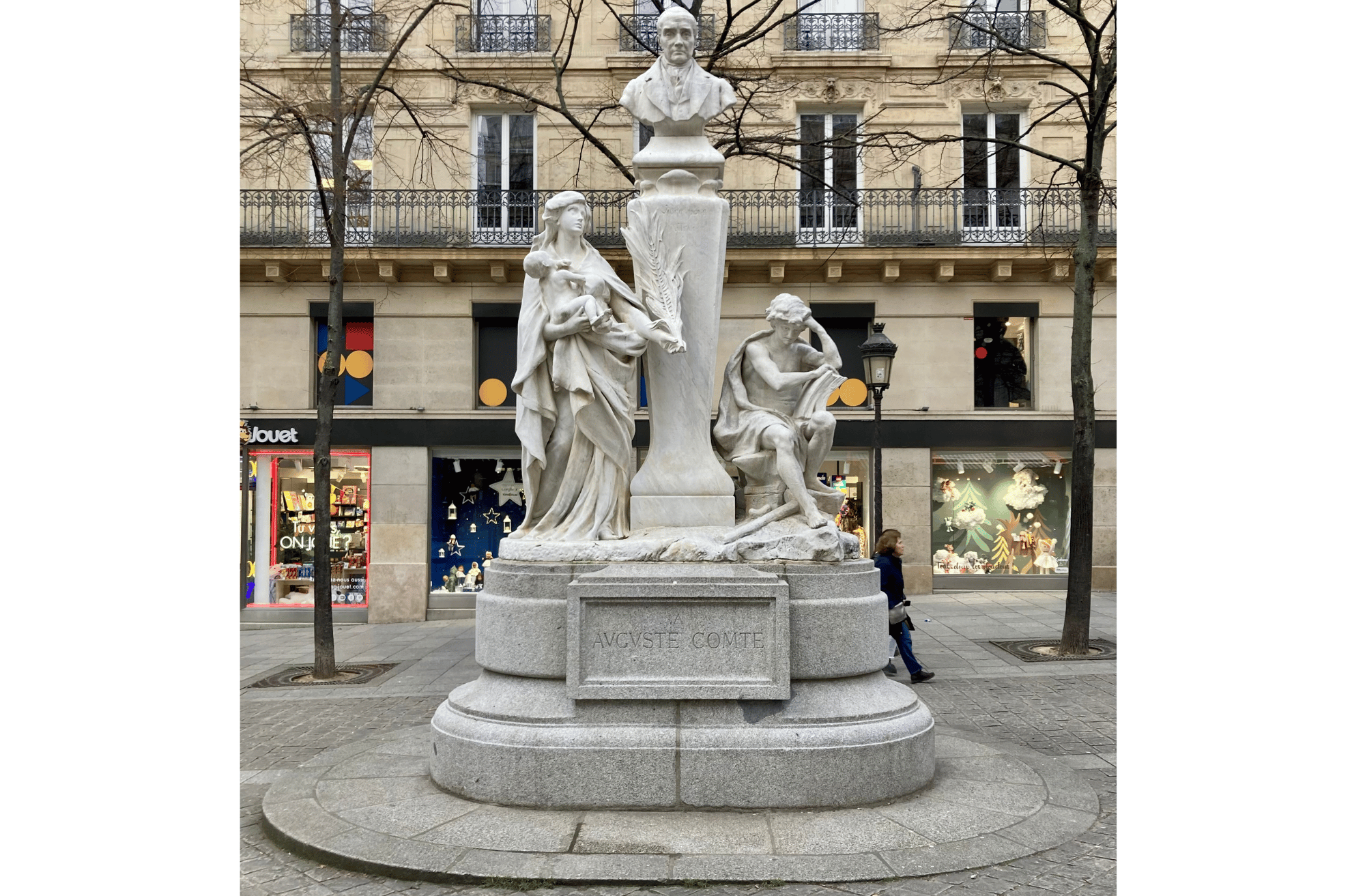

So, when did the West in its sociopolitical modern sense emerge and why? It may come as a surprise to those steeped in the academic literature, but theories inspired by the work of Edward Said, claiming that the West was invented through the othering of the “East” are not relevant here. For West-Europeans were happy for centuries to juxtapose to whatever East they had in mind the self-appellation Christendom or Europe rather than West or Western civilization. Evocation of the West arose only when they had to differentiate themselves from others who were also Christian and European. The other in contradistinction to whom the modern idea of the West was born—the elephant in the room, or rather the bear in the room of the 1815 Congress of Vienna—was Russia. Some incipient explicit calls for a Western federation to defend the rest of Europe from the danger perceived to emanate from Russia emerged in the 1820s in the context of the Greek Revolution. Calls for a Western alliance against despotic Russia intensified in the 1830s. And the first deliberate, explicit, and systematic introduction of an idea of the West, and a proposal for the creation of a Republic of the West that would reorganize European and world politics on a completely new basis came from the French philosopher Auguste Comte—the founder of sociology, positivism, and the “religion of humanity” in the 1840s. It was propagated by Comte’s many and passionate disciples around the world. (A reminder of his extraordinary influence for some decades can be found on the flag of Brazil, adopted in 1889 when the country’s republic was founded by Comtist positivists, which bears Comte’s motto Ordem e Progresso [Order and Progress]).

The twist in the story is that the idea of the West was not invented in the last two decades of the 19th century to promote the aims of high imperialism (as the current academic orthodoxy has it) but first thoroughly articulated and promoted as part of a passionately anti-imperialist political project: Comte’s pacifist and altruistically inclined Republic of the West. This does not mean that many different, in some cases widely different, conceptualizations of the West (including ones that justified and promoted imperialism) were not articulated by others later. But the idea was not born to serve imperialism, and thus inherently or quintessentially imperialistic. Neither was the idea of the West primarily Anglo-American, with the “Anglosphere” at its core. On the contrary, it started being used in Britain later than in France and in German-speaking lands, and it reached America even later (primarily through German influences).

There is not one idea of the West. And yet, to quote the 19th-century historian Arnold Heeren, “names are not matters of indifference in politics.” The concept of the West has accumulated a lot of associations over centuries. Users stress some of them more than others in different situations, according to what they want to achieve. What is to be done then? The best response to the polysemy of meanings of the West is a genealogical study of its long history. Friedrich Nietzsche was right that one cannot define something with a long history; one can only study the different layers of meaning that have been successively deposited and have been fighting to impose themselves. What is crucial is that the meanings that prevailed in earlier stages do not completely disappear when others are superimposed, and that they leave some traces that may resurface in different circumstances.

In his famous 1993 article “The Clash of Civilizations?”, Samuel Huntington stressed “civilization consciousness,” yet such consciousness is partial among members of what he labeled “Western civilization.” But there are notable exceptions to this that are relevant in the context of Mitteleuropa. It was a Polish president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, who declared that, if it happened, Brexit could be the beginning of the destruction of not only the European Union but also of “Western political civilisation in its entirety.” It was an Estonian student who asked me the question with which this article will conclude. And it was no accident that Warsaw was where, in 2017, President Donald Trump gave a speech replete with references to the West and Western civilization that were otherwise completely dissonant with his isolationist, America First and anti-NATO rhetoric. It is unmissable how often it is people from Central and Eastern Europe—Milan Kundera and Czesław Miłosz’s “kidnapped West”—whose countries recently escaped the clutches of Soviet and Communist rule, who most explicitly assert and even celebrate their newly refound membership of Western civilization or the West. Today, the West is still evoked by people who want to differentiate themselves from Russia—a Russia that cannot be wished away from being part of Europe. There are many other examples of layers of the historically deposited meanings of the concept of the West resurfacing according to circumstances. These are things that can only be fully appreciated through a longue durée study of the history of the idea of the West.

When, in July 2022, I gave a lecture related to this topic in Tallinn, a doctoral student from Tartu University asked me a challenging question. The timing was crucial. With the war in Ukraine having recently begun, people in the Baltic republics were intensely nervous about Russia’s next moves. Henry asked me whether I was not worried that, by exposing the many different and contradictory meanings of the West, and somehow deconstructing the idea, I might help undermine our new-found unity? I took it that the unity in question referred to most Western states’ solidarity with Ukraine. I replied that the answer was implicit in the question and reminded the audience that the majority of Ukraine’s population is Christian Orthodox. The vast majority of the definitions of the West I had spoken about (and of the even greater number analyzed in my forthcoming book, The West: The History of an Idea) would not have included Ukraine in the West. In fact, Huntington predicted in the 1990s that there would never be serious violence between Ukrainians and Russians because they are members of a “Slavic-Orthodox civilization.” And yet, since 2022, the West has in some sense been fighting Russia by proxy alongside Ukraine. (Similar things could be said of Orthodox Greece, which Huntington more or less proposed to expel from NATO). Was that not the answer to Henry’s question? The West was, once more, being redefined as we spoke.

At the time of writing this article one cannot help speculating about potential redefinitions after January 2025. Depending on who has Trump’s ear, the United States may or may not project itself as the leader of the West. If it does not, one cannot exclude the possibility that other countries may see an opening. (France, for example, could be one to do so as there are many definitions of the West to justify it seeing itself as the heart of the West.) There are many precedents for such realignments and metamorphoses in the long story of the history of the idea of the West.

Georgios Varouxakis is professor of history of political thought at Queen Mary University of London. He was a guest at the IWM in 2024.