“What the historians say about the period of normalization is of course true. But I don’t remember it that way.” These words of a Czech philosopher express the reason why philosophy in the 20th century gave much attention to the problem of the witness. Derrida, Lyotard, Didi-Huberman, Šmíd. Classic analyses of the witness. But a hidden gem hides elsewhere: in the encounter of Deleuze with Bacon.

It might seem surprising with regard to the situation of a philosopher writing about a painter, but the conception of a witness that Gilles Deleuze draws from Francis Bacon’s paintings describes anything but an eyewitness. Witnessing has nothing to do with sight and the visible realm. It is all about sensation, about the Logic of Sensation, as the title of Deleuze’s book about Bacon reads.

What parts of the past can historians grasp and represent in the form of knowledge? Events, processes, transformations, transgressions, transmutations of politics, transitions of ideas, transfigurations of landscapes, transparencies of texts. Sure. But does the reader of a historiographical book understand anything about sensations? Who knows? However, sensations constitute an indispensable element of the past, and every understanding of the past that omits them fails to fulfil its mission.

Understanding sensations is a matter of witnessing. The witness witnesses a sensation and feels a gap between his or her memory of the past and the information provided about it by historiography. For historiography tries to provide a clear and precise view of history, whereas sensation is a matter not of sight but of the body. It cannot be viewed; it can only be experienced.

But speaking of the body goes a little too far in the context of Deleuze talking about Bacon. The body, as an organism, plays only a secondary role here. It is the flesh that comes first, as the bearer of sensations. And the witness matters as somebody who experienced a certain event and is standing in the flesh before those to whom he or she is presenting his or her witness account.

Numerous thinkers have stated that the important part of a witness account is not the actual content of the words spoken but the expressive element of the presentation of the account. The pauses, tone of voice, specific articulation. Something irreducible to information, something expressing the emotions experienced by the witness, as Georges Didi-Huberman would say. But there is another expressive and more primordial component of the act of witnessing.

When it comes to major historic events of the 20th century, almost all witnesses seemed to agree with regard to the fact that what they were trying to give an account of was unimaginable and unsayable. That is why they had to come up with specific poetics, according to Jacques Derrida, in order to express the unsayable by a poetic detour. Since they could not name directly what they witnessed, they had to wrap it up in a poetic envelope and address it as a letter to the listener, so to say.

Nevertheless, the informative and the poetic contents of the witness account alike are secondary to the presence of the witness in flesh. In the context of Deleuze and Bacon, what matters most is the presence of the flesh of the witness while giving the witness account. The flesh expresses sensations that the tone of voice or rhythm of oral presentation cannot attain. We can thus ask the question of whether the primary act of the witness is giving a witness account or appearing in the flesh before other embodied, “meaty” living beings.

In such a case, history, as far as it concerns sensations of its actors, would be an utmost fragile thing, dependent on living perishable flesh. In addition, it would be transmitted thanks to a specific form of communication between bodies. Maybe even the subtlest touch would be too harsh to become a vessel for it.

As many other painters, Bacon was interested in making the invisible visible. His objects were forces and sensations, and bodies their witnesses. His figures were sensing bodies affected by forces. Contracted, contorted, convoluted, conspicuous, concave, conflux, conditioned. According to Deleuze, Bacon felt the need to incorporate a witness in most of his paintings. Why? Because for a person interested in sensations, every living body is primarily a witness.

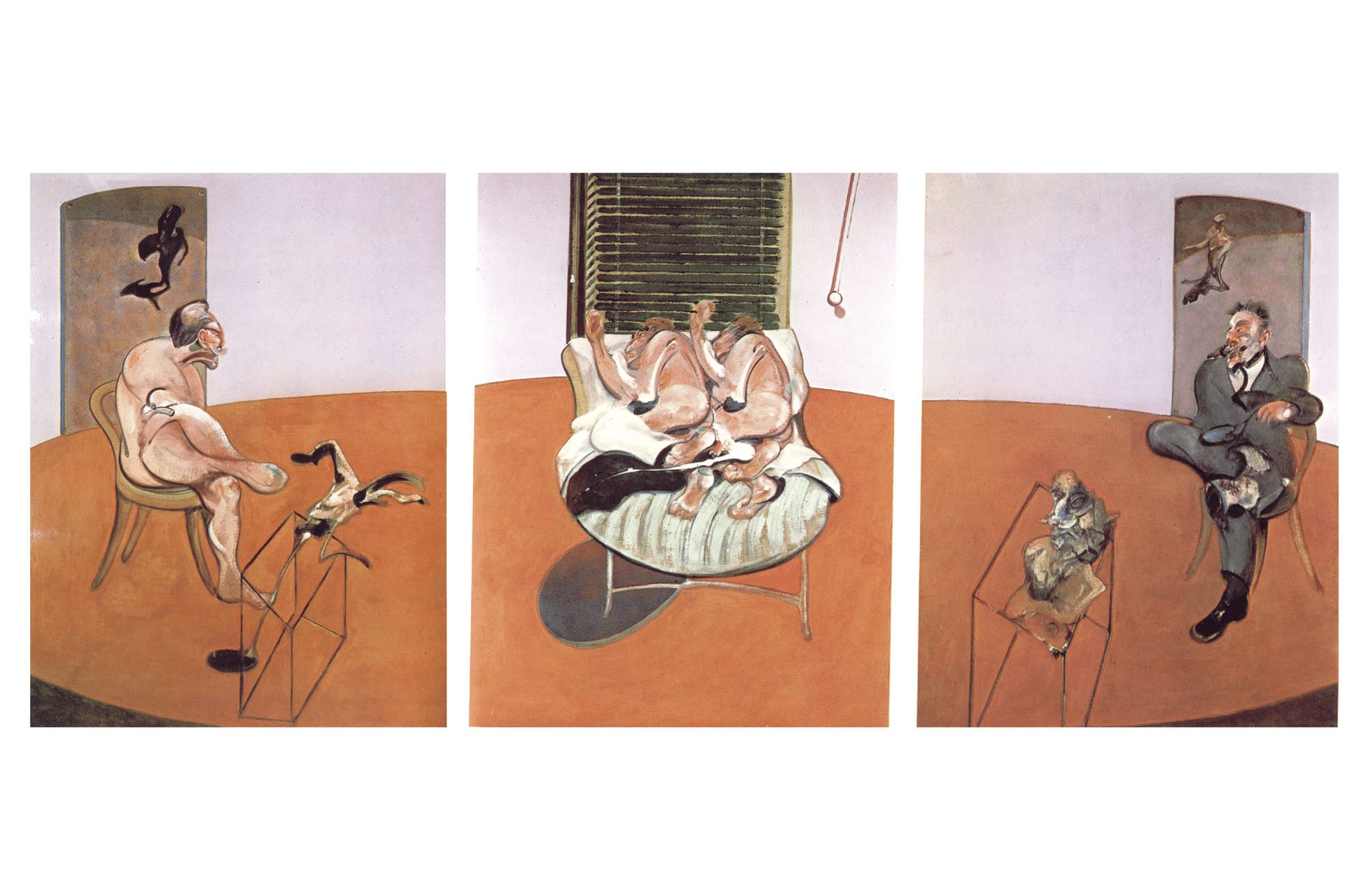

Let us take two examples: Bacon’s triptych Two figures lying on a bed with attendants from 1968 and his Triptych from 1970. They are similar in that they seem to represent the “action” in the middle panel and position the witnesses to the left and right panels. In both works, one witness is naked and the other clothed. Both present the “actor”: in the first case two figures on a bed, in the second case a figure contorted and convoluted by what Bacon called a diagram. The witnesses seem to be looking at the scene in bed and at the convolution.

According to Deleuze, Bacon’s triptychs are anything but expressions of a certain story (or history) or event that is viewed by more or less involved bystanders. The incorporation of three panels is not intended to tell a story. In this regard, Bacon’s use of the triptych resembles Walter Benjamin or Aby Warburg’s use of montage, which also does not strive to present history in a narrative form but to break with the dominant historiographical tendency of their time, the tendency of linking chronologically and causally related events in the form of a representation of history.

Benjamin and Warburg were concerned with the presentation or Darstellung of history. The word Darstellung was intended by them precisely to express the fact of making the invisible visible. Bacon’s triptychs can be viewed from this standpoint as a Darstellung of the event of witnessing.

The act of witnessing does not concern the visible and is itself not visible. The visible witnesses on Bacon’s triptychs are uncovered by Deleuze as non-witnesses on a deeper level. In fact, they represent an active and passive component of the triptych, while the third one, the witness, is presented on the middle panel. The two bystanders are witnesses of a visible event but, in fact, the true witness, the witness of invisible sensation, is the figure in the middle.

The witness is somebody who is being looked at rather than somebody who is looking. It is telling that in Deleuze’s conception looking is active: it acts upon the witness, maybe even producing a sensation in him or her. The witness is one who senses the event of being looked at, while the person that sees the event of a witness sensing his or her stare is an active actor.

An example of this reversal of roles can be Bacon’s triptych Crucifixion from 1965. In its three images, there is no clear eyewitness, while all the bodies are contorted or convoluted (except of two utmost disconcerting men in hats in the background, forming something resembling a tribunal).

The witness is not the crucified figure, Deleuze says. It is an extremely contracted figure with a Nazi band around its sleeve. Deleuze gives his own explanation of the fact, but from our standpoint a hypothesis could be made that the executioner is sensing the look of his victim being pointed at him before its last moment. The flesh senses the force: witness.

Marek Kettner is an assistant professor at the Ladislav Sutnar Faculty of Design and Art in Pilsen. He was a Junior Visiting Jan Patočka Visiting Fellow at the IWM in 2024.