Can an expedition into the history of perspective, through the history of painting and the history of thought, inspire us to address the contemporary problems of societies deeply divided by conflicting perspectives? Reflections on the recent book by Emmanuel Alloa.

Pointing out that something is a matter of perspective often serves as a justification for why there will be different views on the same thing. The term “perspective,” originally denoting the painterly representation of space in a surface, has enjoyed a distinguished philosophical career, dating back to Friedrich Nietzsche, who stated in The Gay Science: “We cannot look around our corner: it is a hopeless curiosity to want to know what other kinds of intellects and perspectives there might be.” This has often been taken as evidence of Nietzsche’s skepticism and ethical relativism. Nevertheless, his reasoning goes on, “today we are at least far away from the ridiculous immodesty of decreeing from our angle that perspectives are permitted only from this angle.” This does not seem like skepticism or relativism but a call for humility and an acknowledgement of the difference of other perspectives. As the reception Nietzsche got shows, what is important is not so much whether or not we are “perspectivists” but what exactly we understand by perspective.

Misunderstanding Perspective

In The Share of Perspective (Routledge 2024), Emmanuel Alloa argues that today we misunderstand what perspective is in two ways. The term “post-truth,” chosen by Oxford Dictionnaries as the word of 2016, is symptomatic of the first one. Denying climate change, rejecting the theory of evolution, or distrusting the efficacy of vaccination is then a matter of perspective. This is the way Alloa reads the term “alternative facts,” used in 2017 by Donald Trump’s adviser, Kellyanne Conway, in relation to the number of participants at the presidential inauguration. In Alloa’s interpretation, the term invokes “the heritage of pluralism and the idea that a multiplicity of perspectives must be taken into account”.

It is tempting to refute such claims by pointing to verified data. Does that mean, asks Alloa, that we should return to factualism and “get rid of the perspectivist error”? This is the second misunderstanding: the idea that truth is to be found beyond any perspective by reference to “brute facts.” For Alloa, this idea has two flaws. First, even if we state as a fact that, say, Rembrandt was born in 1606, it makes sense in a society that uses one calendar, agrees on one meaning of “to be born,” and holds this fact for some reason to be of value. There is a complex framework or perspective behind the interest in such a fact. Second, the defense of brute factuality “reduces intellectual labor to a purely reactive struggle” and “amounts to a call for the death of all critical thought.”

History of Perspective

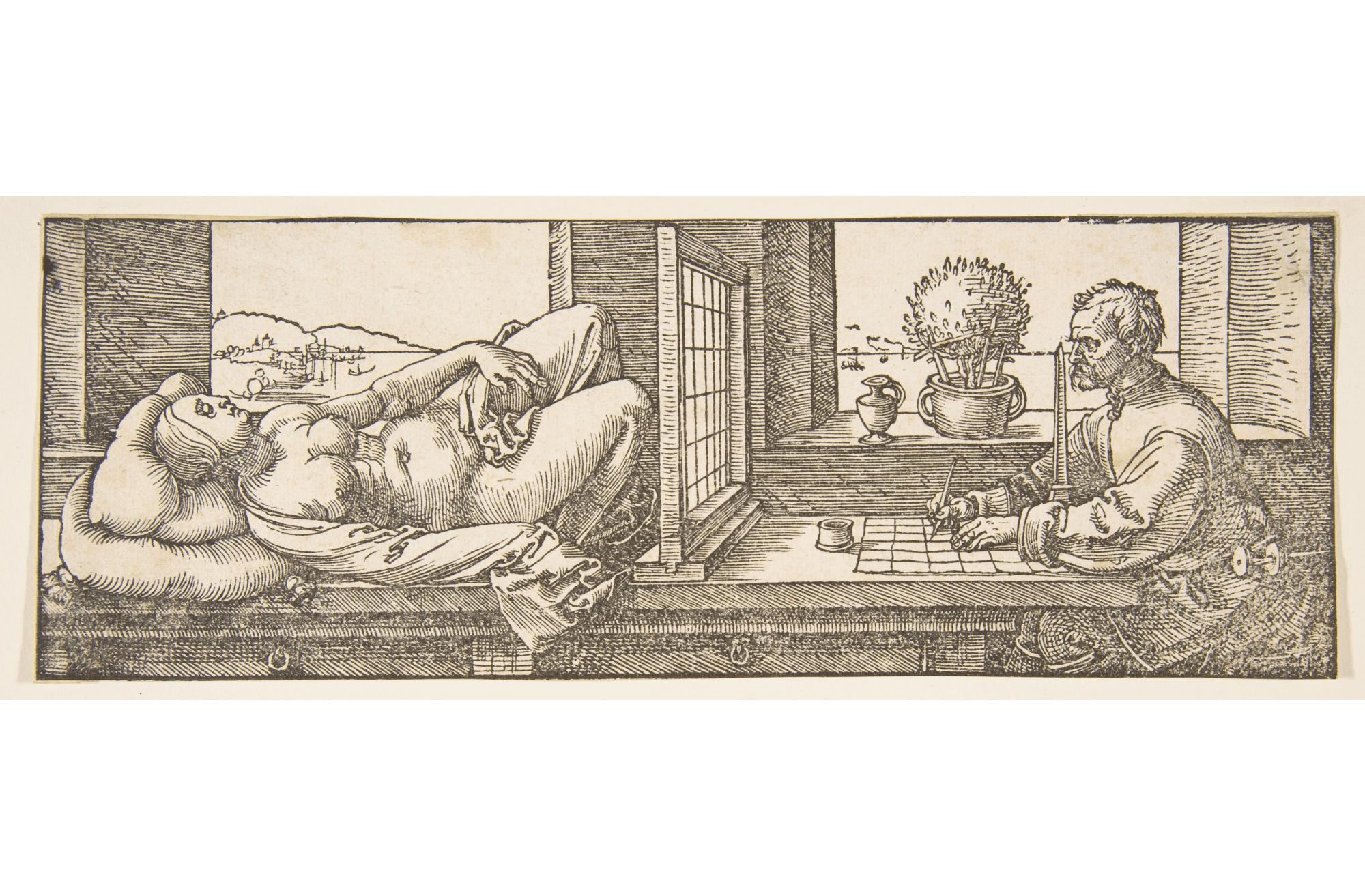

Alloa wrote his book as a “defense of perspectivism in the age of post-truth.” He argues that perspective allows not only for division but also for sharing. Delving first into the history of the concept, Alloa states that perspective is a medium. “Perspectiva is a Latin word that means seeing through”, said Albrecht Dürer at the beginning of the 16th century, referring to the grid used by painters. Perspective is an organizing principle imposed on what we see. One could choose a different perspective than the linear one. And yet, we never perceive without any perspective. The extension of the vocabulary of perspective beyond painting is documented by cases as diverse as the way the subjects see the ruler and the ruler sees the subjects (in Machiavelli, The Prince), the way Europeans saw the inhabitants of the “new world” and vice versa (Montaigne, On Cannibals), the way nocturnal animals that prefer hearing to sight “see” the environment (in Jakob von Uexküll’s analyses), the fact that blood is to the jaguar roughly what manioc beer is to the Native Americans (in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s analyses). One should not forget the novel as a genre associated, from its birth, with a sense of the “relativity of points of view,” the multiplicity of which in Cervantes, for example, encourages not a synthesis of the way Sancho Panza and Don Quixote see things, but burlesque, humor, and joy. The tradition of perspective is continued by artworks and land art installations that break out of the stereotypes of the central perspective. Robert Smithson in works such as Gyrostasis stages “a gaze gazing onto nothing but its own loss,” thereby initiating an experience of the absence of perspective.

Promises of Perspective: Sharing

Post-truth claims fall under a kind of perspectivism that Alloa calls “reclusive.” It elevates one’s own perspective to a single view and is thus a combination of closedness and universality (which is encouraged by social networks, for example, by their increasing personalization of the content offered). What he recommends against this autistic perspectivism is “diagonal” perspectivism. This takes seriously the “conflict of perspectives.” Everything boils down to the question of what idea of sharing Alloa is promoting when he speaks of the “conflict of perspectives” as something to be shared. He offers two types of conflictual sharing.

First, the hunter trying to shift into the perspective of the prey to better hunt it or the warrior attempting to understand “the enemy’s point of view.” Here, the claim that perspective is shared implies no cooperation whatsoever. It states only a formal structure of experience that is well compatible with the absence of sharing in the actual course of experience: the hunter kills an animal, the warrior defeats an opponent, the conqueror wipes out the indigenous inhabitants (also thanks to the ability to share perspective). There is no empathy, participation, or bond.

Second, when jointly perceiving and discussing a work of art or a movie, we might conflict, yet the fundamental situation is one of co-perception (Maurice Merleau-Ponty). In such a sharing, the “dispute shapes the collectivities that are involved” and makes it impossible to “return to unilateral standpoints.”

In these two sets of observations, a different understanding of conflict is at work. A confrontation between prey and hunter is different from a dispute over the interpretation of an image in the art gallery. While in the second conflict, knowledge of the other perspective can enrich both of them, in the case of the first it contributes to the victory of one side at the expense of the other. In articulating the book’s central claim that perspective enables sharing, Alloa relies on the second and downplays the first.

Conflict of Perspectives: What Conflict?

What significantly reduces Alloa’s contribution to understanding the perspectives that divide society is the fact that he limits himself to an epistemological view of perspective. Lacking is the ontological understanding of perspectivity, present in some of his own sources (Merleau-Ponty or Hans-Georg Gadamer): perspective is not a way of seeing only but also a way of being. The paradigm example from Merleau-Ponty is not the one of two people contemplating the same countryside (or painting), but a person trying to regain balance (after losing it on an uneven surface) or trying to reshape their life-orientation after a severe loss (of a close person). When regaining one’s balance or reshaping one’s orientation, the person in question interacts with other people and events, seeing them from a certain perspective as supportive, obstructive, or indifferent. Perspective makes part of the search for orientation, which for Merleau-Ponty is synonymous to being. Gadamer uses the perspectivist vocabulary to point out that, when reading an ancient text or facing an uncertain future, we stand in our tradition or “standpoint.” Contrary to the epistemological take, the primary focus is not on this or that reality but on the orientation of someone’s being (balance regained, life scenario reconstructed, a communal life organized to face a future). The reality is not to be observed from a perspective but something to be taken into account or denied, as in the cases of the traumatic denial of a loss, in the way one shapes an orientation. An orientation has always a temporal aspect (a future) and a reality reference (things and events seen from a perspective).

When confronting post-truth and factual falsehood in general, it is not enough to refute it. In this, Alloa is right. Claims such as “the attack on Ukraine was not unprovoked” (my example) are divisive. As Alloa states, they are “undermining the belief in a common and shared world,” and he is right here too. And yet, his epistemological take seems to grasp not the core of the conflict but its manifestations. What should stand in focus is the orientation out of which these reality claims are made. The question is not whether we can share certain claims about reality, but whether (and why) we share an orientation that builds the precondition for such claims. There is a conflict of orientations beyond the conflict of perspectives.

Jakub Čapek is associate professor in philosophy at the Charles University Prague. He was a Paul Celan Fellow at the IWM in 2024.