The European Jewish refugee experience in Bolivia is often told in sunny generalizations: The refugees thrived in exotic Bolivia; they opened Viennese cafes and founded the national symphony orchestra. After the Second World War, most of these grateful Europeans remigrated with warm memories. A simple tale, and a relatively happy ending. But the reality was more complicated.

Through the story of Erich Eisner, a German composer and conductor from Prague, this essay looks at anti-Semitism in Bolivian politics and elite culture, and its complicated parallel with the country’s elites attitudes toward the local indigenous population. The refugees were themselves the objects of racism; Jewish “whiteness,” in wartime Latin America as in Europe, was at best insecure or provisional. Bolivia’s elites were dubious about the role of indigenous peoples and cultures in its modern state. This left room for some refugees and elites to make common cause. Eisner’s Bolivian career, including the music he played, wrote, and conducted, reflected these tensions.

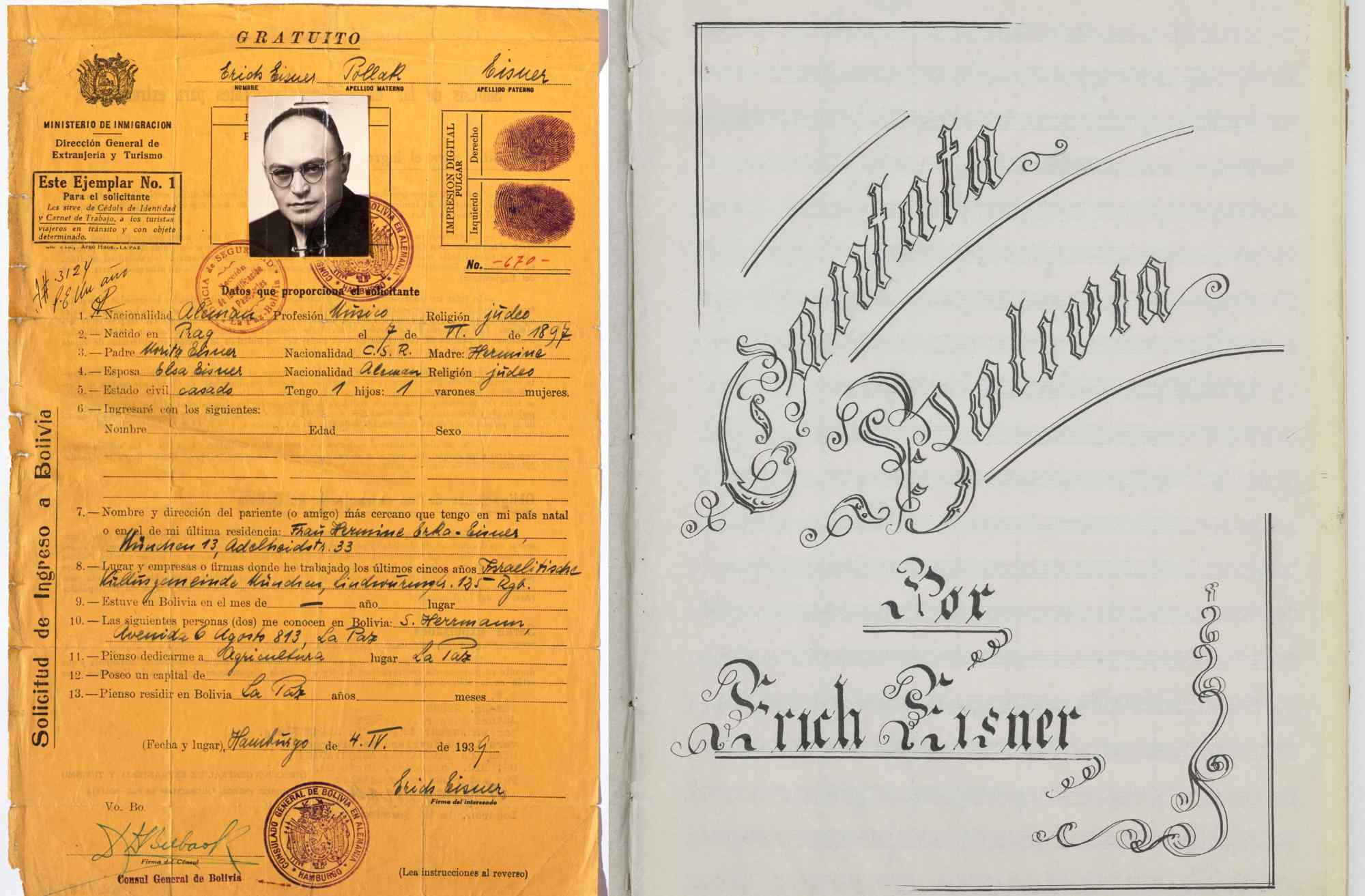

Erich Eisner entered Bolivia in 1939. His family followed him a year later. By 1940, the train from the Chilean port of Arica up to Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, was known as “el exprés judío,” or the Jewish Express. Bolivia is rightfully famed for its unusual willingness to allow in Jewish Central European refugees, with estimates of the total ranging from 8,000 to 20,000. The Eisner family first landed in an immigrant hostel in La Paz. Erich found only occasional work giving piano concerts, and the family struggled. In 1940, he was offered a job in Sucre, as a professor at the Escuela Nacional de Maestros, where he taught music teachers. He slowly created a Central European-style choir of 265 singers. At local performances, and later on government-supported tours across Bolivia, Eisner’s choir sang classics like Händel’s Messiah or Haydn’s Creation alongside work by Bolivian composers. Additionally, he directed a philharmonic society that brought Sucre’s professors and students together to perform at the Teatro Mariscal. Eisner’s work in Sucre, and especially his choir’s national tours, helped him establish a national reputation.

During the same years, antisemitism, almost nonexistent prior to the mass migration, gained currency across Bolivia. As European Jews arrived, elite antisemitism grew, driven in part by dynamics in global Catholicism and by Nazi influence. The Bolivian officer corps, especially younger officers, was generally friendly to Nazism. Latin American anti-imperialist sentiment could easily veer into antisemitism, as when the far-right Revolutionary Nationalist Movement claimed that the Jewish refugees, and the liberal elites who had helped them immigrate, had sold out Bolivian interests to the United States. The Catholic hierarchy, especially priests of Italian and Spanish origin, were sometimes forthrightly antisemitic. Nazi Germany’s embassy supported these ideas through propaganda and its backing for the radical-right political press.

In 1944, the government asked Eisner to return to La Paz to create a national symphony orchestra and to work as professor of counterpoint and composition in the National Conservatory. That same year, he composed his only large-scale piece, the Cantata Bolivia, based on Quechua-language poetry by Yolanda Bedregal de Konitzer, which praised the landscape and people of Bolivia.

Eisner’s cantata offers a glimpse into the involvement of European refugees in the Latin American aesthetic movement known as indigenismo, in which nationalists “envisioned the creation of a national culture based upon cosmopolitan renditions of Indian culture deemed superior to the Andean indigenous original.” Indigenistas throughout the Andean region held up a romanticized version of supposedly elite Inca culture as a preferred set of references and practices. Indigenismo and anti-indigenous prejudice coexisted easily and often, however. Rural Andean indigenous and mestizo populations were systematically excluded from full civil rights. Throughout the region, indigenismo often amounted to a neo-Incan façade over a tacit policy of Hispanization.

Bolivian indigenismo dated back to the 1920s, when the state sponsored “Incaic” folkloric ensembles and musical work, hoping to draw on the Inca past to create a unified national artistic culture. During the 1932–1935 Chaco War with Paraguay, radio networks expanded beyond the standard repertoire of European classical music to include far more Bolivian folkloric and indigenista music. Those behind the first efforts to create a Bolivian national orchestra called on the indigenista José María Velasco Maidana, composer of the “Inca ballet” Amerindia, to lead the ensemble, but the negotiations failed.

Against this backdrop, it is less odd to encounter Eisner and Bedregal’s Cantata Bolivia, which combined a somewhat unimaginative Austro-German melody with Quechua lyrics written by a white, Spanish-descended criolla—that is, European-refugee-inflected indigenismo. Similarly, it is unsurprising that Eisner, a Habsburg German Jew, was tasked simultaneously with creating Bolivia’s national symphony orchestra and a state-sponsored indigenista ensemble.

Since the late nineteenth century, European classical music, played by a standing orchestra maintained by public funds, had been a means of establishing national prestige across Latin America. Appreciation of European art music was an important sign of respectable middle-class identity. Eisner’s orchestra was to demonstrate Bolivia’s entry onto the world stage as a civilized nation. To build a professional symphony orchestra, Eisner had to poach musicians from the National Conservatory and draw on his refugee colleagues from Sucre. He did the work of music librarians and copyists, since he had no staff. Without the instruments he needed, he reorchestrated.

But Eisner also led the Orquesta Típica Nacional, a state-sponsored folkloric ensemble, playing an all-Bolivian repertoire on weekly radio programs and in La Paz concerts, including free performances for workers and peasants on Sunday mornings at the Teatro Municipal. This work involved telling compromises and critiques. For example, the resolution creating the ensemble specified the use of only “autochthonous” or indigenous instruments. But European instruments—guitars and mandolins—were easier to obtain in La Paz, and were preferred by audiences as well as local music critics.

The Orquesta Tipica Nacional and Eisner’s cantata represent a basic aspect of indigenismo, even as practiced by a European Jewish refugee: the intention to rescue or civilize. Actual indigenous agency was not at all the point. In this context, the European refugees fit quite comfortably into their new homelands, Bolivia included.

But Bolivian indigenismo also served as a foil for growing antisemitism and anti-European frustrations, especially after 1938. Antisemitic sentiment had been supported for years by the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement, a neo-fascist party that combined indigenista propaganda and what its leaders called “tactical antisemitism” to strengthen its claim to speak for a unified Bolivia. The party’s paper, La Calle, printed antisemitic propaganda.

Many refugees were reminded too closely of Nazism. Some Jewish businesspeople were even jailed. Jews in Bolivia recalled feeling that they lived in a waiting room or on a trampoline, ready to bounce to another country. Within ten years of the end of the Second World War, thousands of them did. So it was for Elsa Eisner, who went home to Munich in 1957 after her husband died in La Paz. As it turned out, the Jewish Express into Bolivia was generally not a one-way ticket. And Eisner’s cantata, scheduled for its initial premiere in 1943, did not play in Bolivia until 2004, by which time its composer and the circumstances of its creation were merely curiosities.

This article presents in Bolivian miniature the larger arguments of my book, Music in Flight: Migration From Hitler’s Europe and Musical Politics in Latin America, which focuses on European classical musicians within the larger Holocaust refugee population in Latin America.

Andrea Orzoff is associate professor of history and honors at New Mexico State University. She was a guest of the IWM in 2023.