Defining the ‘Geopolitical Commission’

Geopolitics is a term coming from the study of International Relations. At the most basic level, it refers to the interaction between geographic factors and a state’s foreign policy. More elaborate definitions understand it as the study of national foreign policies in light of the global distribution of military and economic resources and the respective power dynamics.

Applying the notion to the European Commission means moving it to the supranational level and applying it to an institution with limited powers to act on behalf of the geographic area it represents. The distribution of competences between the European Commission, other EU institutions, and the member states is clearly delineated by the Treaties and varies depending on the issue area. The Commission has, for instance, the competence to act on behalf of the EU in the field of trade, but defence and military matters remain national competences. The Commission’s ability to bundle the EU’s political, economic and military resources to influence global dynamics is thus not only limited, but also highly variable.

Concrete Implications

Beyond this more abstract conceptual dimension, the geopolitical framing has concrete implications for the Commission’s level of ambition, priorities and working methods. Von der Leyen promised an EU that would champion multilateralism, promote open and fair trade, set global standards, achieve technological sovereignty, and become more autonomous in defence matters.

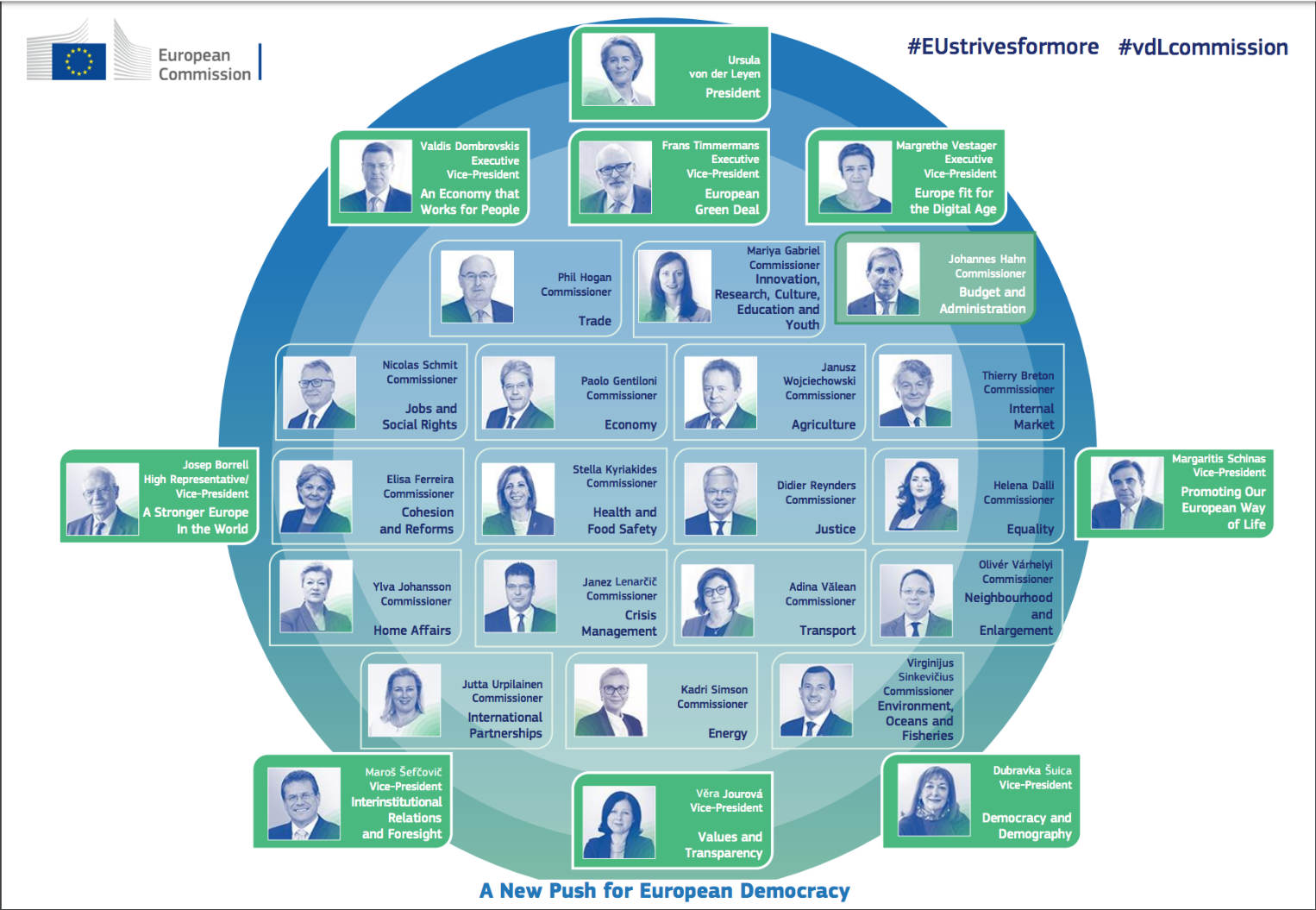

She also promised a closer link between the internal and external aspects of Commission portfolios. The mission letters outlining the tasks of single Commissioners show that almost all the internal portfolios explicitly include external priorities (see table below). The underlying logic is that the EU can only wield power or lead by example externally if it is united and ambitious internally. For instance, it can only credibly put pressure on the world’s other large emitters in international climate negotiations if its own member states stick to ambitious emission targets. Playing the geopolitical game also requires closer links between Europe’s economic and foreign policy. The difficulty of keeping the Iran nuclear deal alive despite the US’s withdrawal underlined the importance of the international role of the euro for the EU’s sovereignty in foreign affairs.

Being "geopolitical" is thus also one of the five guiding principles set out in the Commission’s new working methods. A new Group for External Coordination (EXCO) will prepare weekly discussions in the College on the external aspects of each portfolio. Linking foreign and economic policy will be a key task for the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the Commission (HR/VP) who is to provide the College with a weekly update on foreign policy.

| Commission portfolio | Tasks with an external dimension (example) |

| Agriculture | Promote Europe’s food standards worldwide |

| Budget | Finance the EU’s external policy areas |

| Cohesion and reforms | No explicit external tasks |

| Democracy and demography | No explicit external tasks |

| European Green Deal | Lead in international climate negotiations |

| Energy | Increase the use of the euro in energy markets |

| Environment and oceans | Lead the way on international ocean governance |

| Equality | Promote gender equality internally and externally |

| An economy that works for the people | Strengthen the international role of the Euro |

| Economy | Work on a carbon border tax to ensure that EU companies can compete on a level playing field |

| Europe fit for the digital age | Coordinate work on digital taxation with a view to an international consensus |

| Health | Work with international partners to advocate for a global agreement on the use of and access to antimicrobials |

| Home Affairs | Develop stronger cooperation with countries of origin and transit |

| Innovation and Youth | Foster disruptive research and breakthrough innovations to ensure global competitiveness |

| Inter-institutional relations and foresight | Identify long-term trends likely to drive societal, economic and environmental progress |

| Internal market | Enhancing Europe’s technological sovereignty |

| Jobs | Support reskilling to ensure global competitiveness |

| Justice | Promote the General Data Protection Regulation as a global model |

| Protecting our European way of life | Link internal and external EU migration policy |

| Transport | Improve connectivity links in Europe’s neighbourhood |

| Values and transparency | Countering disinformation and fake information |

Source: own compilation based on mission letters to the Commissioners-designate (2019)

Three key Challenges

The conceptual and more concrete dimensions of the Commission’s geopolitical ambition point towards three key challenges.

First, geopolitical ambition is costly. However, the Commission’s ability to shift financial resources towards its priorities is limited. The negotiations on the EU’s next multi-annual financial framework (MFF) are, as always, controversial and depend on a unanimous vote by the European Council. The Commission proposed raising the shares allocated to newer priorities such as research and innovation, climate, and defence. Yet the proposed amounts may not be sufficient. The Commission, for instance, proposed spending €100bn on research and innovation under the next MFF (2021-27). This is certainly more ambitious than in the past, but it is unlikely to produce technological sovereignty. The proposed envelope is far below the respective budgets of the US, China and even that of single multinationals such as Amazon. Moreover, it is not set in stone. Past MFF negotiations indicate that newer priorities tend to face substantial cuts to preserve the EU’s traditional internal spending priorities, namely cohesion and agriculture.

Second, geopolitical ambition requires power. As mentioned above, the Commission’s ability to act on behalf of the EU is limited and variable. In most cases, it depends on the member states and the more fragmented European Parliament. This also applies to trade, an area of exclusive EU competence and a core element of the Commission’s geopolitical role. It can conclude negotiations on behalf of the EU, but it depends on the member states and European Parliament for approval and, at times, also national or regional parliaments for ratification. Past negotiations with the US and Canada indicate that there will likely be more domestic backlash in this field. Another example for the Commission’s limited power was the Council’s refusal to follow its recommendation to open accession negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania. Due only to the French veto, the EU missed the chance of wielding significant geopolitical influence in its very backyard.

Finally, geopolitical ambition requires intense coordination. This traditional EU challenge is compounded by the cross-cutting nature of von der Leyen’s priorities as well as the growing need to link internal and external policies. The Commission’s new Directorate General (DG) for Defence Industry and Space will be an interesting test case in this regard. The DG will have to coordinate with other DGs such as Internal Market and Transport. Its competences also overlap with those of more intergovernmental players, notably the European Defence Agency and the European External Action Service. The HR/VP is responsible for ensuring overall consistency regarding European defence matters. However, there is no direct link between him and the DG or responsible Commissioner. This set-up could lead to dysfunctional silos and turf wars. The result would be a divide between the defence industrial aspects managed by the Commission and the political ones steered by the Council.

The ‘Geopolitical Commission’ needs Strategy and Allies

The EU’s key weakness in the geopolitical game is that it is a fragmented global actor. The ambition of the incoming Commission might well run up against a more fragmented European Parliament and a divided Council. To deliver on its promise of being more geopolitical, the Commission needs strategy and allies. It should propose a vision of strategic sovereignty in policy areas where it does have substantial powers. At the same time, it will have to forge alliances in Brussels, Strasbourg and the capitals. If the Commission fails to play its part as a powerful driver behind common geopolitical stances, there is a real risk that other players use the EU’s fragmentation to further marginalise its role in the world and in its neighbourhood.

The article gives the views of the author, not the position of the "Europe’s Futures

Ideas for Action" project or the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM).